5 p. An old theater monologue can have more to say about current events than a direct essay.

Is it a dream or an awakening? Is there purpose to the theater, or is purpose now held as pretentiousness?

[This is performed on Youtube in a couple of places. One is an hour, and one is an hour and a half. I will tell you more about it later, maybe in a comment. I present the transcript, also because I shortened it much, and “cleaned-it-up”.]

My name is PERSPECTIVES. Perspectives are different ways to interpret what we see. Perhaps our current perspective is convenient to our lifestyle? That’s why we chose it. Any new perspectives must be introduced gently. We may say that, “even with this new perspective, there is nothing I can really do with it, that makes a difference”. At least I might stop defending the old perspective.

Let’s review where we are and what is going on. This is Substack, and we are readers and writers. And what is the writing? It is the verbal constructs that are turned into images, and this trail of images tells a story. What the necessary images are to tell that story, depend on the alertness of the reader. Some readers are dulled down, and they need a bludgeon to form any understanding. Other readers are quite perceptive and they are going to “get-it” with a few subtle pictures.

In some Eastern wisdom they talk about horses, and they say that the highest breed of horse only needs “the shadow of the whip” to be trained. The common horse needs a belt on the head with a 2x4 plank. These refer to the images that we are talking about.

If your images are out of balance with your reader, the story will collapse, it will be rejected outright. I admit, I went through this excerpt and I sanitized some images. Some of them I left in an inhospitable form, but even those I toned. And the piece is not at all a shocking exposition. Much of it is quite normal. It is that contrast that gives the impact.

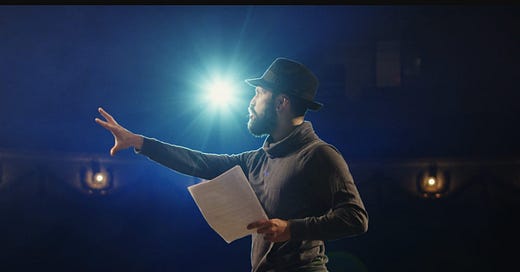

This piece was originally written with the idea in mind that it could be performed in homes and apartments, for groups of ten or twelve. The piece can be performed by a wide range of performers—women, men— older, younger. Here’s a fragment of 5,000 words.

______________

I’d always said, “I’m a happy person. I love life,” but now there was a sort of awful indifference or blankness that was coming from somewhere inside of me and filling me up, bit by bit. Things that would once have delighted me or cheered me seemed to go dead on me, to spoil. Sometimes it was as if someone was strangling me.

I went to a play with a group of friends—a legendary actress in a great role. We stared at the stage. Moment after moment the character’s downfall crept closer. Her childhood home would at last be sold, her beloved cherry trees chopped down. Under the bright lights, the actress showed anger, bravado, and the stage rang with her youthful laughter, which expressed her self-deception. She would be forced to live in an apartment in Paris, not on the estate she’d formerly owned. Her former serf would buy the estate. It was her old brother’s sympathetic grief that finally coaxed tears from the large man in the heavy coat who sat beside me in the theater. But my problem was that somehow, suddenly, I was not myself. I was disconcerted. Why, exactly, were we supposed to be weeping? This person would no longer own the estate she’d once owned . . . She would have to live in an apartment in Paris instead . . . I couldn’t remember why I was supposed to be weeping.

Then someone with whom I'd had a very happy love affair years ago was waiting to meet me. We smiled, we embraced, but I wasn’t there to be embraced. The person I was hugging felt like a doll, electrically warmed. I myself was a funny-smelling doll. In the old apartment, full of memories, we talked about a recent play, a film, a terrible performance by a group of dancers, one of whom we knew, and I heard about the dinner with our friend Nadia, who was working on her painting but also was doing graphic design, and the story of the wooden figures she had smuggled out of Mexico wrapped in clothes.

I remembered that a friend of my mother’s had once said to me, “I like you, because you have such a nice, loud, merry laugh,” and I noticed that now my laugh was like a tight little cough.

And toward the end of dinner our other friend finally told us that his father had died. He described the hospital, the doctors, the machines. It was as if he felt no one had ever died before, as if he felt it was quite unfair that his father should have died. Yet no expense had been spared to extend his father’s life for as long as possible, to make sure that his death was as comfortable as possible. Hardworking experts surrounded his bed doing all they could to see that he would die without feeling pain. I couldn’t help mentioning those others who died every day, some perhaps in torture cells, screaming, surrounded on their bed of death by other experts who were doing all they could to be sure that the ones they surrounded would die in howling agony. It was a deep justice thing. My remarks were totally out of place. Where was the sympathy I owed my friend? His loss was real. He looked at me, appalled.

I thought about Christmas, the streets, the shops. Was that why people brought children into the world—so that they, too, could one day roam through the streets, buying, devouring, always “the best’” for their children and for themselves—the best food, the best clothes, the best everything—so that they, too, could demand “the best”? Were there not enough people in the world who already demanded the best, who insisted on the best? No, we must bring in more, and then we must gather together more treasures from all over the world, more of the best, for all these new children of ours to have, because our children should have the best, it would be our shame, our disgrace, to give them less than the best. We will stop at nothing to give them the best.

Look—here’s a question I’d like to ask you— Have you ever had any friends who were the poor? See, I think that’s an idea a lot of people have: “Why shouldn’t I have some friends who are the poor?” I’ve pictured it so often, like a dream that comes again and again. There’ve been so many people— people who work at menial jobs whom I’ve seen every day—people who’ve caught my eye, talked to me, and I’ve thought, how nice, It’s nice, If only—and I’ve imagined it—but then what I imagine always ends so badly.

Every person is a person, every person believes certain things. My friend Bob—my friend Bob believes that “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” And Fred—Fred believes that “today’s rebel is tomorrow’s dictator.” And Natasha believes that peasants in poor countries just want to be left alone to farm their fields in peace and quiet, and they couldn’t care less about the ideologies of the right or the left. Mario believes that social criticism in plays and films can be expressed most effectively through the use of humor. And Indrani believes that works of art, including performances of opera and ballet, can change individual’s lives, and through them, change society. And Toshiko believes that the only real contribution that people can make toward solving the problems of the world is to raise their own families with good values. And Ann-Marie believes that the rich and the poor should live as friends and should work together to make the future better than the past.

And my beliefs? Yes, yes—I have beliefs, yes— I believe in humanity, sympathy for others—I oppose cruelty and violence— What? You applaud cruelty and violence? No—I said I oppose cruelty and violence— Jesus Christ—oppose, oppose— But I can still remember what I like—can’t I?— if not what I believe. I know what I like. I like warmth, coziness, pleasure, love—mail, presents—nice plates—those paintings by Matisse. . . Yes, I’m an aesthete. I like beauty.

Yes—poor countries are beautiful. Poor people are beautiful. It’s a wonderful feeling to have money in a country where most people are the poor, to ride in a taxi through horrible slums. Yes—a beggar can be beautiful. A beggar can have beautiful lips, beautiful eyes. You’re far from home. To you, her simple shawl seems elegant, direct, the right way to dress. You see her approaching from a great distance. She’s old, thin, and yes, she looks sick, very sick, near death. But her face is beautiful—seductive, luminous. You like her—you’re drawn to her. Yes, you think— there’s money in your purse—you'll give her some of it. And a voice says—Why not give all of it? Why not give her all that you have? Be careful, that’s a question that could poison your life. Your love of beauty could actually kill you. If you hear that question, it means you're sick. You’re mentally sick. You’ve had a breakdown.

Answer the question, idiot. Don’t just stand there. I can’t give the beggar all that I have, because I— because I—

Wait a minute. Wait a minute. I have beliefs. There’s a reason why I won’t give the beggar all of my money. Yes, I’m going to give her some of it—I always give away quite a surprising amount to people who have less than I do— But there’s a reason why I’m the one who has the money in the first place, and that’s why I’m not going to give it all away. In other words, for God’s sake, I worked for that money. I worked hard. I worked. I worked. I worked hard to make that money, and it’s my money, because I made it. I made the money, and so I have it, and I can spend it any way I like. This is the basis of our entire lives.

Why can I stay here in this hotel? Because I paid to stay here, with my money. I paid to stay here, and that entitles me to certain things. I’m entitled to stay here, I’m entitled to be served, I’m entitled to expect that certain things will be done. Now, this morning, for example, the chambermaid left my room a mess. The floor was dirty, there were no clean sheets, and the wastepaper basket was left full. So, I paid to stay here, I paid to be served, I’m entitled to service, but the chambermaid didn’t serve me properly. That was wrong.

Why is the old woman sick and dying? Why doesn’t she have money? Didn’t she ever work? You idiot, you, pathetic idiot, of course she worked. She worked sixteen hours a day in a field, or in a factory. She worked, the chambermaid worked.— You say you work. But why does your work bring you so much money, while their work brings practically nothing? You say you “make” money. What a wonderful expression. But how can you “make” so much of it in such a short time, while in the same amount of time they “make” so little?

___________________

“Read it. Read it.” he screams. I sit on the bunk and start to read this horrible little book.

Sure, it’s just exactly what I expected it to be. The most tedious questions, answered in full, as if a person’s life were a customs form. Chapter One: What country I grew up in, what city, what street? My parents’ race. The money they made. What I was fed. What I was taught.

Chapter Two: This is unbelievable—printed in this book: “Washes hair every day unless ‘in a hurry’ ” quote unquote; “when meeting friends for dinner or going to the theater, takes a bath in the late afternoon, puts on fresh clothes.” What in the world is going on? This has absolutely nothing to do with what I am like, with anything at all that’s important about me! Don’t they know that everything in this book is just as true of—of—of my neighbor Jean, as it is of me, my neighbor Jean who makes jokes about starving children in Asia, my neighbor Jean who boasts about fucking colleagues at the office on the boardroom table? Don’t they know that?

I can't stop thinking about my mother—the way she took care of me—I can’t stand this. I control myself, get a grip on myself. I have to survive. And so, I sit on my bunk and cry and read and cry and read. And time passes—so much time—it seems like forever—and then yes, yes, I understand—I see that there’s an answer to the question I asked. Yes, it could have been predicted, from knowing these things—where I was born, how I was raised—what an hour of my labor would probably be worth—even though, to me, from the inside, my life always felt like a story that was just unfolding right now, unpredictable. Yes, I was born, and a field was provided, a piece of land, from which rich fruit could be plucked by eager hands. And I was taught to be very eager. The beggar, the chambermaid—of course—if you knew—their childhood villages—no, they weren’t taught to be eager— Here is their land, their piece of land—it was barren, black, uncultivable.

I see the whole world laid out like a map in four dimensions—all the land, the people, the moments of time—today, yesterday. And at each particular moment I can see that the world has a certain very particular ability to produce the things that people need: there’s a certain quantity of land that’s ready to be farmed, a certain particular number of workers, a certain stock of machinery, a stock of ideas about how to do things, about how to organize all the ones who will do the work. And each day’s capacity seems somehow so small. It’s fixed, determinate. Every part of it is fixed. And I can see all the days that have happened already, and on each one of them, a determinate number of people worked, and a determinate portion of all the earth’s resources was drawn up and used, and a determinate little pile of goods was produced. So small: across the grid of infinite possibility, this finite capacity, is distributed each day.

And of all the things that might have been done, which were the ones that actually happened?

The holders of money determine what’s to be done— they bid their money for the things they want, each one according to the amount they hold— and each bit of money determines some fraction of the day’s activities, so those who have a little determine a little, and those who have a lot determine a lot, and those who have nothing determine nothing. And then the world obeys the instructions of the demand of money, to the extent of its capacity, and then it stops. It’s done what it can do. The day is over. Certain things happened. If money was bid for jewelry, there was silver that was bent into the shape of a ring. If it was bid for an opera, there were costumes that were sewn and chandeliers that were hung on invisible threads.

And there’s an amazing moment: Each day, before the day starts, before the market opens, before the bidding begins, there’s a moment of confusion: The money is silent, it hasn’t yet spoken. Its decisions are withheld, poised, perched, ready. Everyone knows that the world will not do everything today: if food is produced for the hungry children, then certain operas will not be performed; if certain performances are in fact given, then the food won't be produced, and the children will hunger.

___________________

Look, I’m a human being! Yes, of course I want to make a good wage—What do you think a human being is? A human being happens to be an unprotected little wriggling creature, a little raw creature without a shell or a hide, or even any fur, just thrown out onto the earth like a shucked oyster that’s trying to crawl along the ground. We need to build our own shells—yes, shoes, chairs, walls, floors, and for God’s sake, yes, a little solace, a little consolation. Because Jesus Christ—you know, you know, we wanted to be happy, we wanted our lives to be absolutely great. We were looking forward for so long to some wonderful night in some wonderful hotel, some wonderful breakfast set out on a tray—we were looking forward, like panting dogs, slobbering on the rug—how we would delight the ones we loved with our kisses in bed, how we would delight our parents with our great accomplishments, how we would delight our children with toys and surprises. But it was all wrong: it was never really right: the hotel, the breakfast, what happened in bed, our parents, our children—and so yes, we need solace, we need consolation, we need nice food, we need nice things to wear, we need beautiful paintings, movies, plays, drives in the country, bottles of wine. There’s never enough solace, never enough consolation.

I’m doing whatever I possibly can. I try to be nice. I try to be lighthearted, entertaining, funny. I tell entertaining stories to people. I make jokes to the janitor, every single morning, to the parking-lot attendant, every single morning. I try to be amusing whenever I can be, to help my friends get through the day. I write little notes to people I like when I enjoy the articles they've written, or their performances in the theater. When a group of people at a party were making unpleasant comments about advertising men, I steered the conversation to a different topic, because my friend Monica was feeling uncomfortable because her father works as an advertising man.

__________________

I pick up the book. There’s still the preface—everything that happened before I was born. The voluptuous field that was given to me—how did I come to be given that one, and not the one that was black and barren? Yes, it happened like that because before I was born, the fields were apportioned, and some of the fields were pieced together.

Not by chance, not by fate. The fields were pieced together one by one, by thieves, by killers. Over years, over centuries, night after night, knives glittering, throats cut, again and again, until in the beautiful Christmas morning we woke up, and our proud parents showed us the gorgeous, shining, (blood-soaked) fields which were now ours. Cultivate, they said, husband everything you pull from the earth, guard, save, then give your own children the next hillside, the next valley. From each advantage, draw up more. Grow, cultivate, preserve, guard. Drive forward till you have everything. The others will always fall back, retreat, give you what you want or sell you what you want for the price you want. They have no choice, because they’re sick and weak. They’ve become “the poor.”

And the little book runs on, years, centuries, till the moment comes when our parents say the time of apportionment is now over. We have what we need—our position is well defended from every side. Now, finally, everything can be frozen, just as it is. The violence can stop. From now on, no more stealing, no more killing. From this moment, an eternal civilized silence, the rule of law.

So, we have everything, but there’s one little difficulty we just can’t overcome, a curse: we can’t escape our connection to the poor.

We need the poor. Without the poor to get the fruit off the trees, to tend the excrement under the ground, to bathe our babies on the day they’re born. We couldn’t exist without the poor to do the awful work, we would spend our lives doing awful work. If the poor were not poor, if the poor were paid the way we’re paid, we couldn’t afford to buy an apple, a shirt, we couldn’t afford to take a trip, to spend a night at an inn in a nearby town. But the horror is that the poor grow everywhere, like moss, like grass. And we can never forget the time when they owned the land. We can never forget the death of their families, those vows of revenge screamed out in those rooms that were running with gore. And the poor don’t forget. They live on their rage. They eat rage. They want to rise up and finish us, wipe us off the earth as soon as they can.

And so, in our frozen world, our silent world, we have to talk to the poor. Talk, listen, clarify, explain. They want things to be different. They want change. And so, we say, Yes. Change. But not violent change. Not theft, not revolt, not revenge. Instead, listen to the idea of gradual change. Change that will help you, but that won’t hurt us. Morality. Law. Gradual change. We explain it all: a two-sided contract: we'll give you things, many things, but in exchange you must accept that you don’t have the right just to take what you want. We're going to give you wonderful things. Sit down, wait, don’t try to grab— The most important thing is patience, waiting. We’re going to give you much, much more than you're getting now, but there are certain things that must happen first—these are the things for which we must wait. First, we have to make more, and we have to grow more, so more will be available for us to give you. Otherwise, if we give you more, we'll have less. When we make more and we grow more, we can all have more—some of the increase can go to you. But the other thing is, once there is more, we have to make sure that morality prevails. Morality is the key. Last year, we made more and we grew more, but we didn’t give you more. All of the increase was kept for ourselves. That was wrong. The same thing happened the year before, and the year before that. We have to convince everyone to accept morality, and next year give some of the increase to you.

So, we all have to wait. And while we’re waiting, we have to be careful. Because we know you. We know there are some who are the violent ones, the ones who won’t wait. These are the destroyers. Their children are dying, sick—no medicine, no food, nothing on their feet, no place to live, vomiting on the streets. These are the ones who are drunk with rage, with their lust for revenge. We know what they’ve planned. We’ve imagined it all a thousand times. We imagine it every single day. That sound at the door—that odd “crack” — the splintering sound—then they break through the lock and run in yelling, pull us up from where we're gathered at the family table, having our meal, pull our old parents out from the bathroom, pull the little ones up from their beds, then they line us all up together in the hall, slap us, kick us, curse us, scream at us, our parents bleeding, our children bleeding, pulling the children’s clothes from the closets, the toys from the shelves, ripping the pictures off the walls. What will they do to us? we ask each other. What?—are they giving all our homes to people who now are living in the street?

Then terrible stories—shops torn apart, random killing, the old professor given a new job: cleaning toilets at the railroad station. It seems impossible—can that possibly have happened? A mob of criminals—or unemployed louts—people who a year ago were starving in slums? Are they going to be running the factories now, the schools, everything, the whole country, the whole world?

We have to prevent it, although the violent ones are everywhere already, teaching the poor that the way things are, is not God-given, the world could be run for their benefit. And so, we have to set up a special classroom for the poor, to teach the poor some bloody lessons from the past—all the crimes committed by the violent rebels, by the followers of Marx or whomever. Shove the lessons of history down their throats. History, history. Their crimes. The oppression. The famines. The disasters. Teach the poor that they must never try to seize power for themselves, because the rule of the poor will always be incompetent, and it will always be cruel. The poor are bloodthirsty. Uneducated. They don’t have the skills. For their own sake, it must never happen. And they must understand that the dreamers, the idealists, the ones who say that they love the poor, will all become vicious killers in the end, and the ones who claim they can create something better will always end up by creating something worse. The poor must understand these essential lessons, chapters from history. And if they don’t understand them, they must all be taken out and finished off. Inattention or lack of comprehension cannot be allowed.

And in places where we find that the classroom is avoided, we must warn the poor that even the innocent are all going to get hurt. We can’t accept violence against the symbols of law, the soldiers, the police. We have to suppress the ones who commit those crimes. But if the violence goes on for a long time, then the ones whose older sisters and brothers we’ve already killed may be so full of rage that they don’t fear death. And to control those people, we may have to go farther—cut their tongues, cut up their faces, force them to watch us torture their parents, watch the soldiers rape their children. It’s the only way to control people who don’t fear death.

And so, we'll teach the poor that yes, yes, we’re going to give them things, but we will decide how much we'll give, and when, because we’re not going to give them everything.

And now the ugly little book is back at Chapter One, and I read it again, and Chapter Two, and I read it again. And it’s as if a voice is coming up slowly from my throat. Like vomit, Stop!

________________________

Everyone has always been so good to me. No. - Listen. I want to tell you something. You've misinterpreted everything. The old woman who bent down and gave you sugar-covered buns did not love you. You were not loved the way you thought.

Of course I still feel an affection for myself— someone so happy, so cute, funny—?—

No; I’m trying to tell you that people hate you. Why do you think that they all love you? I’m trying to explain to you about the people who hate you. And what do you think they would love about you? What are you? There’s no charm in you, there’s nothing graceful, nothing that yields. You're simply a relentless, unbearable fanatic. Yes, the commando who crawls all night through the mud is much much less of a fanatic than you. Look at yourself. Look.

You walk so stiffy into your kitchen each morning; you approach your cupboard. You open it, and reach for the coffee, the coffee you expect to find on its shelf. And it has to be there. And if one morning it isn’t there— oh, the hysteria!—the entire world will have to pay! At the very thought of the unexpected, the unexpected deprivation, you begin to twitch, to panic, to pant. That shortness of breath! Listen to your voice on the telephone, listen to the tone that comes into your voice when you talk to one of your very close friends and you talk about your life and you use those great expressions—‘“what I need to live on. . .”—‘“the amount I need just in order to live. . .”

Are you cute then? Are you funny then? That hollow tone—‘“the amount I need...” —solemn, quiet, no histrionics—the tone of hysteria, the tone of the fanatic—well, yes—of course—it makes sense. You understand your situation. Without a place to live, without clothes, without money, you would be like them, you would be them, you would be what they are— you would be the homeless, you would be the comfortless. So of course, you know it, you will do anything. There are no limits to what you will do. Without the money, your face would become the face of a rat, your hands would be paws— sharp, nimble, ready to scratch, ready to tear.

Sure, sometimes you think about the suffering of the poor— Lying in your bed, you feel a sympathy, - you whisper into your pillow some words of hope: Soon you will all have medicine for your children, soon, you will have a home. The heartless world, the heartless people, like my neighbor Jean who laughs at suffering, will soon give way, and gradual change will happen.

But during this period of waiting, waiting, this endless waiting for gradual change, one by one they come knocking at your door and they cry out, they beg you for help. And you say, Get them away from me. I can’t stand this constant knocking at my door, these people who come with these ridiculous stories, who claim to be my sister, who claim to be my brother, all day long, day after day.

And so all of these people are taken away, and they’re made to live in places where they’re teased, they're played with, they’re lectured, mocked, until a few of them begin to rave irrationally and even laugh, viciously, and then their vicious actions fill absolutely everyone with horror. And then each one of these vicious people is taken by the shoulders and held down, and their head is shaved, and they’re strapped into a chair, and with a flip of the switch they’re executed, and the one they’re being executed for is you, just as it was always you that all those people were talking about so many years ago when they kept on saying, “For our children’s sake, we have to do it, we have to set this town on fire, this barn, this hospital, these forests, these animals, this rice, this honey,” just as it’s still you, because of how much you love those clean white sheets and the music and the dancers and the telephone calls, for whom all those people with radiant faces are being abused tonight, are they dying tonight? Maybe some of them are.

.