5. The Generals coup d'état 1991, Yeltsin, and the 1993 Ostankino affair.

The enduring image of the ordeal was of Yeltsin standing on a tank in a flak jacket, portrayed as a clash between public democracy and totalitarian conspiracy – but it does not quite fit the facts.

Here we are backing up to the time of dissolving the Soviet Union. The State Emergency Committee (GKChP) coup cemented Boris Yeltsin, president of the Russian Soviet Republic, as the dominant leader of the land and stripped the hardliners of their legitimacy. This drove a stake through the heart of the Union, leading directly to its demise four months later.

[We had some good comments that some authors have a built-in bias. I ask if there is any such thing as a neutral history? With these many details on the Ostankino affair, (I had never heard of it), you can be the judge if this account is plausible. In this thread I am looking to fill in the circumstances that we all have missed.]

Total word count 5,430; Shortened version 3,000 words. (Drop down link works on-line, but not in the email.)

Click this link to drop to the short version.

____________

But exactly what happened during the three tense days after Gorbachev realized that his phone lines had been cut is still hotly disputed by experts. The following day, 19 August, the morning sun rose on a column of tanks rumbling down Kutuzovsky Prospekt, a broad avenue that leads from the western suburbs towards Moscow’s city center. Alexander Dugin remembers being woken by his wife Natasha, and hearing the radio broadcast announcing that, for reasons of ill health, Gorbachev was handing over power to his deputy, Gennady Yanaev, ‘It’s our coup!’ The coup’s unwitting propagandists (Dugin) had little inkling of what was to come, ‘completely surprised’ by the rapid sequence of events,

But from the very first day, the coup was in shambles. The first mistake was obvious: as soon as Lukyanov’s address was finished, state television and radio began to play a continuous loop of Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky’s tragic opera of the triumph of evil over good. But not using the radio and TV to buttress their case with citizens was only the first of many mistakes the plotters made.

Today, Gorbachev is remembered as the reformer who “peacefully” broke the back of communism and then voluntarily bowed out of history with the fall of the USSR in December 1991. But back in August of that year, his main political opponents were not the hardliners (whom he cultivated, along with reformers, in an effort to secure his political survival), but Yeltsin, who in June of that year had been elected president of the Russian Soviet Republic, which gave Yeltsin a broad political mandate alongside the popular charisma of a reformer.

Yeltsin himself, after years of backing Gorbachev’s version publicly, told a television interviewer from the Russian channel Rossiya in 2006 that, that in the days before the putsch, he and other reformers had tried to convince Gorbachev to fire Kryuchkov, but that Gorbachev had refused: ‘He [Gorbachev] knew about this before the putsch began, this is documented, and during the putsch he was informed about everything and all the while was waiting to see who would win, us or them. In either case he would have joined the victors.’

The GKChP was complete improvisation. There were no plans, no one planned to arrest Yeltsin or storm the White House [the Supreme Soviet building]. We thought the people would understand us and support us. But they all hurled abuse at us for sending tanks into downtown Moscow.30

Yeltsin standing on the tank

On the afternoon of 19 August, Yeltsin drove into Moscow from his dacha, apparently passing unawares the KGB team that had been deployed in the forest with orders to arrest him. In Moscow, he walked out of the White House, mounted that tank that had defected to his side, and made his famous television address: ‘I call on all Russians to give a dignified answer to the putschists and demand that the country be returned to normal constitutional order.’ Protests held that day were not broken up, and foreign television crews moved around Moscow unhindered.

US President George H.W. Bush had ordered that Yeltsin should be provided with sensitive communications intelligence about what Kryuchkov and Yazov were telling their ground commanders. ‘We told Yeltsin in real time what the communications were’, wrote Seymour Hersh, quoting a US official.31 It does appear that the commander of the KGB’s Alpha commandos tried to order his men to storm the White House at 3 a.m., but his subordinates again refused, saying they were being ‘set up without written orders, for the nth time’, to take the blame.

Yet in the three days that sounded the death knell of the Soviet Union, only a total of three people lost their lives (in an accident), and 11 went to prison for a matter of months. The highest drama was Yeltsin’s made-for-TV spectacle of mounting a tank in front of the White House and addressing the public – yet this was a CNN footage and was not even seen inside the USSR.

Yeltsin, the president of the Russian Soviet Republic, who before the coup had already been working on plans for a Russian secession from the Soviet Union, now redoubled his efforts. In December of that year, he met the chairman of the Ukrainian Communist Party, Leonid Kravchuk, and Stanislav Shushkevich, chairman of the Belarusian Supreme Soviet, in the Belovezh forest resort near Minsk, and dissolved the Union, presenting Gorbachev with a fait accompli.

One-quarter of the territory of the Soviet Union seceded over the next few months, and on the 25th of December the Soviet flag was lowered from the flagpole of the Kremlin forever, to be replaced with the tri-color of Democratic Russia.

The GKChP had delivered a victory for Yeltsin, but not a decisive one. He still had to contend with a profoundly divided society, as well as with a bureaucratic apparatus and security services that were overwhelmingly loyal to the old order, which they had secured their privileges from.

‘Deep states’ – conspiracies by military and security men to rule from behind the scenes – are a regular feature of new and unstable democracies. A small elite, well represented in the military or security services, will, almost without exception, feel it is too risky to cede full control to a civilian constitutional government. This is both on account of concern for its own privileges, and because of a well-justified fear that politically immature societies are easily seduced by populism and demagoguery. It is a fact that such ‘deep state’ plots are actually known to have existed in several modern states in the post-war era. One of the best known (thanks to several court cases beginning in 2008) is the derin-devlet, ‘deep state’ in Turkish, in which the military and security services of Turkey sought to guide successive civilian governments from behind the scenes, through decades of turmoil.

There’s the P2 Masonic lodge in Italy, which is so legendary that it is hard to separate myth from reality. But several respected researchers have come to the conclusion that it is not a myth: they argue that it did in fact sponsor right-wing terror and had links to the CIA, with serving generals, bankers and admirals as members. Meanwhile, successive military dictatorships in Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Argentina and Chile in the post-war era, through the 1970s and 1980s, all follow this model of a military–security ‘deep state’, which periodically intervened when the politicians lost their way, and then stepped back into the shadows during periods of civilian rule.

Communism enjoyed zero prestige as an idea, while Russian nationalism, the other competitor in the field of opposition ideologies, had just led to the dissolution of the USSR.

‘Operation Crematorium’

In 1993, amid economic shock therapy that plunged Russia into crisis, the situations of the democrats and the patriotic opposition were reversed. Once ascendant, Yeltsin’s camp very rapidly lost support to a growing opposition nationalist mood, stoked by hardliners in the system.

The economy was mostly to blame. Yeltsin had come to power on the promise that democracy would usher in an era of Western-style economic prosperity; instead, in 1992 the economy collapsed. In January of that year came the first market reforms, which saw prices rise by 245% per cent that month alone, creating widespread panic. Hyperinflation wiped out the savings of the university professors, bureaucrats and intellectuals who, just a few months before, had been the strongest bulwark of liberal reforms. The balance of opinion in the Supreme Soviet shifted fast. Hundreds of deputies who had once backed Yeltsin drifted into the opposition camp.

The nationalists, whose initial experiences at the ballot box had been farcical, began to gain popular support, becoming a political threat to Yeltsin. And it was he – the selfsame politician who, just two years before, had faced down tanks – who ultimately would be forced to rely on armed force to secure his power.

Politically, the reformers were in trouble. There were mass defections from the democratic camp to the side of the patriotic opposition. Ruslan Khasbulatov, an economist who was speaker of the Supreme Soviet, and even Yeltsin’s own vice-president, former fighter pilot Alexander Rutskoy, joined the opposition against him.

Yeltsin deftly managed to shed most of the blame for the dislocation caused by economic reforms and push it onto his prime minister, the 35-year-old whiz-kid Egor Gaidar (who was in, and out of power according to Yeltsin’s mood), AND his privatization chief, the enigmatic economist Anatoly Chubais. Yeltsin was still popular: when parliament threatened to impeach him, he held a referendum and won 59 per cent of the vote. But his influence was nonetheless waning, and Russia’s political system slid towards conflict once again. Throughout the summer of 1993, Yeltsin plotted to dissolve parliament and hold fresh elections, while his opponents still planned to try again to impeach him. But neither could garner the political support to finish the other off.

The events of September–October 1993 would lead to armed conflict in the center of Moscow, the worst fighting there since 1917, and very nearly to full-scale civil war. The motives and behavior of both sides remain extremely puzzling to this day. After the conflict was over, US President Bill Clinton said Yeltsin had ‘bent over backwards’ to avoid bloodshed; however, there is accumulating evidence that bloodshed is exactly what he wanted – to do militarily what he could not do politically: destroy the opposition, suspend the constitution, and unilaterally redress the balance between executive and legislative powers to create a super-presidency. That is exactly what he got.

On 21 September, Yeltsin struck, signing ‘Decree 1400’ dissolving parliament. He freely admits in his memoirs that this was an unconstitutional measure, but ironically it was the only way to defend democracy in Russia, he claimed: ‘Formally the president was violating the constitution, going the route of antidemocratic measures, and dispersing the parliament – all for the sake of establishing democracy and rule of law in the country.’ ??

Again, at the center of the stand-off was the famed White House, which was a familiar symbol of freedom to Western television viewers – the very place where Yeltsin had stood stalwart and called for resistance to the generals’ coup in August 1991. This time the tables were turned: Rutskoy and Khasbulatov were ready and they barricaded themselves in the White House. The political confrontation turned increasingly ugly with each passing day, as the city of Moscow turned off the electricity and water to the building. But parliament held firm, voting to impeach Yeltsin, who was on thin legal ice in dissolving parliament. For days the confrontation hung in the balance. The army did not want to become involved in politics, as it had been in 1991 and during the various independence struggles around the Soviet Union which had preceded its break-up. However, it became clear that only the army could eventually decide the outcome.

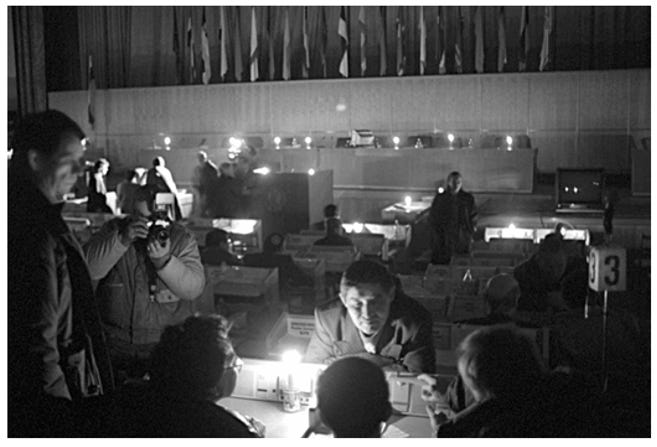

Inside the besieged White House with electricity turned off

Curiously, while electricity to parliament was cut off immediately, it took a week before the Interior Ministry put a cordon of razor wire and police around the building – a delay that allowed political leaders, ex-generals, thrill-seeking teenagers, disgruntled pensioners and everyone in between to flood in. They all milled around inside the building, meeting by candlelight, with no one visibly in charge.

Vladislav Achalov, a former tank commander who was drummed out of the army for supporting the August 1991 coup, was the acting defense minister, appointed by Rutskoy. He made the fateful decision – in retrospect a bad miscalculation – to appeal to paramilitary patriotic opposition groups to join the defenders. Thus Dugin, Prokhanov, Limonov and other nationalists joined the parliamentary defenders in the gloomy candlelit darkness. Dugin was deeply unimpressed: ‘There was chaos. Everyone was wandering around, they thought they would receive new government posts, that they would rule the country. Nobody thought they would simply be shot.’

The arrival of fighters and radical extremists was welcomed by Khasbulatov and Rutskoy as an extra show of muscle. But throwing in their lot with the nationalist opposition would ultimately prove a gigantic mistake. They were out of their depth. They thought they would be fighting for control of buildings and neighborhoods, when the real battle was for television screens and world opinion.

That was the only thing constraining Yeltsin. He did not lack muscle – he used only a handful of the 6,000 riot police during the crisis.4 He had army Special Forces units, tough-eyed commandos under the command of the Federal Security Service (FSB – the successor to the KGB) and the Interior Ministry; and although it remained officially neutral, he also controlled the army. The Taman Motor Rifle Division, which had roared into Moscow two years previously, was based an hour away, as was the Kantemirov Tank Division. The only thing Yeltsin lacked was the legitimacy to use the force arrayed at his disposal. If he had he declared a state of emergency and fired on parliament during the first day, there would have been an outcry worldwide and probably a mutiny within the armed forces. But the appearance of gangs of communists, mercenaries, crypto-fascists and neo-Nazis may have provided the spectacle he needed to justify the use of force, and to call parliament a ‘fascist communist armed rebellion’, which he did on 4 October, an hour before tanks opened fire.

Ilya Konstantinov, a former boiler-room worker who was head of the opposition National Salvation Front, recalls:

“It was obvious that [the paramilitary groups] were compromising the whole parliament. I don’t even think they were aware they were doing it. But by the time they were in the building, we couldn’t get them out. We couldn’t eject them without a fight, and no one wanted that.”

International public opinion, initially wavering and unwilling to tolerate violent repression of parliament by the Yeltsin administration, gradually swung in the president’s favor as Khasbulatov and Rutskoy faltered and erred.

For two weeks, the siege was static, as parliamentarians and protesters milled around the darkened White House, meeting by candlelight, going home every day to take showers and shave. Rebel leaders tried to whip up support in the streets, and gangs of opposition protesters clashed frequently with police. Yeltsin, meanwhile, used the airwaves to coax the population over to his side.

HERE’S WHERE THE DROP-DOWN STARTS

There was little bloodshed until 3 October, when the momentum seemed suddenly to shift in favor of the mutineers. A massive crowd gathered in Moscow’s October Square, under a statue of Lenin, and began marching north along the ring road, towards parliament, in a bold attempt to break the police blockade of the building. They overwhelmed an outnumbered detachment of riot police on the Krymsky Bridge, capturing weapons and capturing ten military trucks; and then, to their utter astonishment, police surrounding parliament gave way after a small scuffle, surrendering to protesters. The crowd then broke through the police lines surrounding parliament, breaking the blockade.

In the euphoria, as they massed in front of the building, the protesters waited to be told what to do next by the very confused leaders of the revolt. From the balcony of the White House, Khasbulatov said to move on the Kremlin; Rutskoy said NO, to go to Ostankino – the needle of a tower from where the city’s radio and television signals are broadcast, and which houses the offices of the main national broadcasters. As the crowd decided on Ostankino, the battle appeared to hang in the balance. No loyal military units barred the way of the 700-odd protesters who set out on the ring road towards the television tower, driving in captured military trucks and school buses. Dugin, Limonov and Prokhanov were among them, hanging off the backs of trucks or crammed into buses. ‘The city seemed to be ours’, said Limonov. ‘But it only seemed that way.’

The man leading the protesters to take the TV tower was General Albert Makashov. Riding in a jeep with a few heavily armed bodyguards, he led the motley motorcade around the ring road and towards Ostankino. As they drove, he looked out at the road and saw ten armored personnel carriers (APCs) roaring alongside. ‘Our guys’, he assured his men. He appeared to believe that the APCs were carrying mutinous forces that had switched sides to join the protesters. But he was wrong. They were, in fact, transporting a unit of 80 commandos from the elite Vityaz battalion of the Interior Ministry’s Dzerzhinsky Division, still under Yeltsin’s control, that had been scrambled to defend the TV center. Their vehicles drove right alongside those of the protesters for most of the way.5 One account of the day, albeit on a pro-rebel website known only as Anathema-2, deserves some attention. It (and numerous witnesses) reported, fairly plausibly, that the Moscow ring road at Mayakovsky Square was blocked by Vityaz APCs, and that, more incredibly, the column of armed demonstrators in vehicles had stopped in front of it, but was allowed to continue.6

The protesters and the Vityaz commandos arrived at Ostankino at roughly the same time. Sergey Lisyuk, the Vityaz commander, says he was given the order via radio to return fire if fired upon. ‘I made them repeat it twice, so those riding next to me also heard it.’7 The soldiers, arrayed in body armor and clinking with weaponry, ran through the same underpass as the protesters and entered the building. Meanwhile the protesters set up outside with megaphones and heavy trucks. Nightfall was drawing near. The protesters were jubilant, toting truncheons and riot shields captured from police. Eighteen of them had assault rifles and one had an RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Makashov, the former general who commanded the armed men, ordered the vehicles to turn around and ferry more demonstrators, until the crowd outside the TV center numbered over a thousand. Journalists arrived in vans and jeeps, dragging tripods and hurriedly unwinding cables. Inside, the Vityaz men, in grey camouflage with black balaclavas, could be seen scurrying around erecting barricades and taking up firing positions.

Night fell. It was around 19:20 when General Makashov, wearing a black leather overcoat and black paratrooper beret, addressed the Vityaz defenders inside Ostankino: ‘You have ten minutes to lay down your arms and surrender, or we will begin storming the building!’ The Vityaz men made no public response, though negotiations between Makashov and Lisyuk were ongoing via radio, according to numerous accounts.

Truck ramming the door

At 19:30 a group of protesters brought in a heavy military truck, captured that day from riot police, to try to break into the television compound. Over and over, it battered against the glass and steel entrance, trying to smash through; but it was unable to get through the concrete building supports. Near the truck squatted the man toting the grenade launcher. Details of this man, including his last name, are scant, though Alexander Barkashov told me his name was ‘Kostya’ and he was a veteran of the Trans-Dniester conflict of 1990. Other witnesses say that he was a civilian, and did not know how to fire the grenade launcher until a policeman who had joined the parliamentary mutiny showed him how. What happened next is still the subject of a great deal of controversy. To this day, the specific actions that led to the carnage at the TV center are still debated, but what can be established is that as the truck was smashing its way into the compound, snipers on the upper floors of the building opened fire. Simultaneously, an explosion reverberated on the lower floors of the TV center, and a Vityaz private named Nikolay Sitnikov was killed. Colonel Lisyuk said the soldier was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade fired from the crowd. He said his men opened fire in self-defense, and only after Private Sitnikov’s death.

Every witness has a slightly different memory. Dugin recalls that a Vityaz soldier fired a shot which hit the leg of the man with the grenade launcher, who accidentally triggered his weapon: ‘The Vityaz men started shooting people, unarmed people. At first some started shooting back, three or four machine-gun rounds, and that was it, later the shooting was only from Vityaz.’ Prokhanov saw the grenade man fall. He ‘suddenly began to sit, to slip along a wall. Nearby the twilight flashed and a small cloud of concrete debris was lifted into the air by a bullet strike.’ That was his description of the scene, taken from Red Brown, his (very) semi-autobiographical novel about the events, published the following year.

Tracers flew out of the TV center. Bullets cracked overhead and thudded into bodies. ‘A wave of heavy red explosions covered us all’, according to Limonov. He dropped to his belly and crawled away. At one point he looked back to where he had been standing, near the truck, and saw 20 bodies, ‘some of them were groaning, most said nothing’. Tracer bullets rained down on the crowd for over an hour. At least 62 people were killed in the mêlée, mainly bystanders, but also several journalists.

Dugin wrote movingly about the tragedy, finding esoteric meaning in the events. In one account of the chaos, he described how he had ‘felt the breath of spirit’ during the massacre, when, seeking cover, he dived behind a car and accidentally pushed someone who had already taken cover there into the open. Instead of shoving him angrily ‘as a live human body should involuntarily do’, the man simply embraced him, exposing himself to fire and shielding Dugin from the shots. Dugin wrote of the transcendent spiritual feeling ‘above the flesh and above life’ which he felt, being under fire for the first time.

‘It was a day of severe defeat’, he wrote seven years later, ‘when it seemed that not only our brothers and sisters and our children, but also the huge structure of Russian history had fallen.’8 He spent most of the night under the car, and finally crawled away into the nearby stand of trees after the shooting subsided, finding Oleg Bakhtiyarov, one of Makashov’s bodyguards, who had been shot in the leg. Dugin flagged a car down, took Oleg to hospital, and went back to the Duma at about 3 a.m. The mood was somber, as news of the scale of the catastrophe at Ostankino filtered back. ‘That’s when I understood that our leaders were bastards, that they started this war, they started this confrontation, they sent people with no weapons, no instructions, to die. They simply committed a crime.’ Knowing the end was coming, Dugin left parliament in the small hours of the morning.

To this day Lisyuk defends the actions of his Vityaz men: ‘The firing was aimed only at those who were armed, or who tried to obtain arms’, he said in a 2003 interview. However, he added:

“Try yourself to figure out, in the dark, who is a journalist and who is a fighter … I don’t have any guilt – I followed orders. Of course, I feel very sorry for the ones who died, especially the ones who were innocent. We were all victims of a political crisis. But I want to say the following: the price would be high if the military did not follow orders”.9

However, Colonel Lisyuk’s version is disputed, and a number of inconsistencies add to the mystery of exactly what, and who, caused the massacre. Leonid Proshkin, the head of a special investigative team from the Russian general prosecutor’s office, spent months investigating the parliamentary uprising. He found no evidence that a rocket-propelled grenade had hit the building because there was no damage found that was consistent with such an explosion:

Such a grenade can burn through half a meter of concrete, the grenade from an RPG-7. And all that was there were marks from a large-caliber machine gun, from an APC. It all boiled down to this: if Sitnikov had been killed by an RPG, it would have looked completely different.10

Proshkin determined that the wounds received by Sitnikov, and the damage to his bullet-proof vest, were not consistent with an RPG-7, which is designed to penetrate tank armor. Rather, it was likely caused by a simple hand grenade:

Sitnikov died not from the firing of the grenade launcher from the direction of Supreme Soviet supporters standing near the entrance, but as a result of the explosion of some sort of device located inside the building, that is, in the possession of the defenders.11 It remains possible, therefore, that Sitnikov’s death was either an accidental grenade detonation or, more ominously, the result of a provocation aimed at goading the building’s nervous defenders into massacring the crowd.

For Yeltsin, Ostankino was a tragedy; but a tactical success in his duel with parliament. It was portrayed on TV screens and newspapers across the world as an armed attack by protesters on the TV station, coming in the wake of the successful seizure of the mayor’s office. It was possible (and partly true) for the Kremlin to say that, rather than massacring dozens of nearly defenseless demonstrators, they had repelled an armed attack.

After Ostankino, the end of the conflict was no longer in doubt. At 7 a.m. on 4 October, several T-80 tanks positioned themselves across the Moscow River from the White House. They were manned entirely by officers. Meanwhile, commandos from Alpha Group reluctantly took up positions around the building, waiting for the order to storm it.

It was during the lead-up to the operation that another mysterious tragedy occurred. As the Alpha detachment was exiting their APCs, one of the soldiers was hit by a sniper and mortally wounded. Korzhakov – Yeltsin’s former KGB bodyguard, who took a leading role in managing the 1993 parliamentary crisis – writes of this incident in his biography. Seeing one of their own killed, he said, had brought Alpha’s fighting spirit back: ‘Suddenly their military instincts returned, and their doubts vanished.’12 To this day, however, the mysterious shooting is debated. After his retirement, Gennady Zaytsev, the Alpha commander at the time, gave an interview saying that the shot did not come from the White House, but rather from forces loyal to President Yeltsin in the Mir Hotel.13 He made the incendiary accusation that the shot had been a deliberate attempt to provoke his forces: ‘It did not come from the White House. That’s a lie. That was done with one goal in mind, to make Alpha angry, so that we rushed in there and cut everyone to pieces.’14 If true, it might cast new light on the killing of Private Sitnikov the previous day, which had provoked the massacre at Ostankino by the Vityaz commandos.

Korzhakov disputed this account, saying in an interview that Zaytsev was ‘in a bad psychological state’ during the operation: ‘And how anyway is he able to tell where [the soldier] was shot from? Did he do proper police work? Did he line up the body and take measurements? No. They took the guy off the battlefield alive; it was only later he died.’ Zaytsev said, however, that he understood the situation immediately, and despite what he believed to be a provocation that had cost a young soldier his life, he ordered the operation to go ahead: ‘I understood that, if we completely refuse the operation, Alpha would be disbanded. It would be the end.’15 However, he is sure in retrospect that the reason Alpha was transferred to the Ministry of Security’s control after the conflict was that it did not perform its duties ‘using different methods’ – i.e. taking the building by force and killing Rutskoy and Khasbulatov.

The identity of the sniper, the killer of the Alpha soldier, remains one of the key mysteries yet to be unraveled in the events of that October, just like the explosion at the Ostankino tower. If Alpha, the elite soldiers of Russia’s intelligence service, were themselves merely rats in the maze of a broader conspiracy, it is chilling to think of who could have been higher up the food chain.

Shortly before 9 a.m., one of the T-80 tanks fired a 150mm shell at the White House, hitting the top floors. There followed several more shells, likewise aimed at the top floors in order to avoid killing the building’s occupants on the lower floors. The shelling was mainly symbolic, to break the morale of the defenders. Nonetheless, some 70 people are believed to have been killed, including some bystanders. After the shelling, the Alpha commandos positioned around parliament moved in and led the mutineers out peacefully.

Ultimately, the snipers firing on the pro-Kremlin forces throughout the siege of the White House were never found nor tried. Korzhakov suggested that they belonged to the Union of Officers and had escaped from the White House via tunnels, under the Moscow River and out of the Hotel Ukraine on the other side. Security Minister Nikolay Golushko was thought to have sealed these tunnels off but had not, according to Korzhakov.

The events of late 1993 were grist to the mill of conspiracy theorists, reflecting the overwhelming conviction of the parliamentary defenders that they had been the victims of a great deception, designed to lure them into a trap. The Red Brown (an allusion to communist/nazi) protesters now believed that Ostankino had been a set-up – that the trucks they had captured from riot police (with keys still in the ignition!) were part of a grand strategy to goad them into the killing fields outside Ostankino, where they could provide their own pretext for getting massacred. They claimed to have been emboldened by specially planted disinformation concerning the supposed defection of army units to their side. They had – in the version described on Anathema – even been allowed through a roadblock on Moscow’s ring road, all for the sole purpose of providing a provocation aimed at giving Yeltsin the excuse to use tanks against parliament.

Prokhanov’s account of the events is encased in his surrealistic fantasy novel Red Brown, which described the fictional ‘Operation Crematorium’: a conspiracy by Yeltsin and his American puppeteers aimed at trapping the patriotic opposition in the kill-zone of Ostankino and the smoking tomb of the White House. But the use of provocateurs by the regime may not simply have been a figment of Prokhanov’s vivid imagination.

This became apparent when I interviewed Alexander Barkashov about his role in the 1993 confrontation. I had to drive for three hours to his dacha outside Moscow, where he keeps fighting dogs and a collection of hunting bows. As the evening wore on, he became more and more conspiratorial, until eventually I asked him why he had taken part on the side of the parliamentary defenders. He dumbfounded me by replying that he had been acting under the orders of his commander in the ‘active reserve’, by which he meant the retired chain of command of the former KGB. He identified his commander as acting Defense Minister Achalov, the same man who had originally issued the call for armed nationalist gangs to come to the aid of the White House defenders: ‘If Achalov had told me to shoot Khasbulatov or Rutskoy, I would have done it.’ If his claim is true, it would explain a great deal. Barkashov played the role of a provocateur in the parliamentary siege, discrediting the defenders in the eyes of world opinion by publicly aligning them with neo-Nazis. Curiously, Barkashov’s forces from Russian National Unity (RNU) did not take part in the Ostankino siege, and the party lost only two members killed in the fighting.

Achalov flatly denied the accusations: ‘I’m just a tank soldier, nothing more. I don’t know what Barkashov is talking about.’ If Barkashov, in his own words, was acting not according to the convictions of an ideologue, but on the orders of a state structure, then the goals of that structure must be wondered at. The rise of nationalism in post-communist Russia may have been a far more complicated event than first meets the eye.

.