The monolithic western stereo-types about Mao and the cultural revolution

Dongping Han 2008. "The Unknown Cultural Revolution": Life and Change in a Chinese Village. Book Review by Munir Ghazanfar, uploaded by him on 24 July 2018.

Munir Ghazanfar Lahore School of Economics

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326571861_Dongping_Han_2008_The_Unknown_Cultural_Revolution_Life_and_Change_in_a_Chinese_Village_New_York_Monthly_Review_Press_Reviewed_by_Munir_Ghazanfar

I don’t know about Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Abusive leaders were humiliated and made to apologize publicly. Mao called them “capitalist roaders” within the party. Some (or many), may have been beaten or even killed. It is a very big phenomenon and there were major differences between the villages and the large cities.

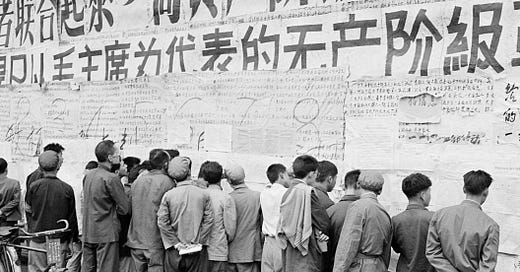

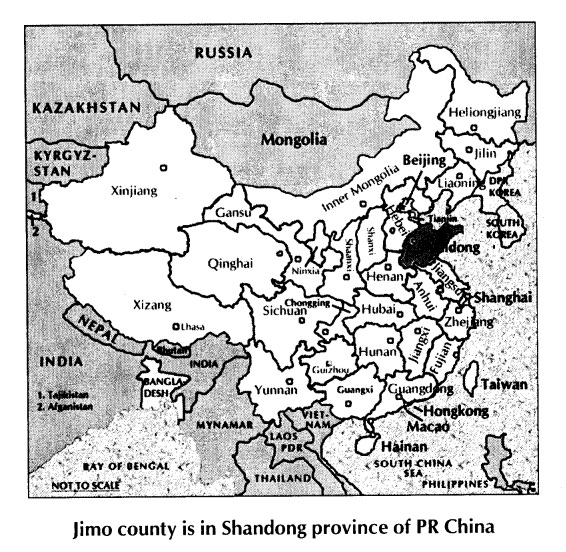

This book opens a window only on what happened in the rural villages of Jimo County, Shandong Provence, and near the major port city of Qingdao. Dongping Han is a native of the area and returned there for a study on his Doctorate Degree. He writes of NO killings and I think no beatings. The main tool of this revolution in the villages where the “sida” (big character posters, the great debate, the great airing and great political freedom). Peasants were allowed to air their grievances about the village leaders on public walls with these posters. They probably did demand public apologies. The county administrators still held their power positions, but lost their excessive privileges. (I chose the title graphic to show big character posters, but in the villages I think they would have been smaller, and focused on certain individuals.)

The Review

Dongping Han 2008. The Unknown Cultural Revolution: Life and Change in a Chinese Village, New York: Monthly Review Press. Reviewed by Munir Ghazanfar.

Soviet Union and China were two major revolutions of the twentieth century. However now, both have changed course from socialism to market economy. It is generally believed it happened because the revolutions proved inefficient and unsustainable in economic terms. According to Mao it was because of class war and the question of who would win had still not been decided in China even by the mid-1970s. Han’s book is an investigative record of class struggle and the changes that occurred in the rural areas during that final period class struggle which overturned the revolution in China. It is not an account of what transpired at the Central Committee level but of what happened at the village and commune level. The Cultural Revolution was ten-year epic battle fought to keep China on revolutionary track. It was lost with the death of Mao Zedong in 1976.

Two phases of recent Chinese history

China today competes with US in most indicators at variable level including economic, scientific, technological, agriculture, education and defense. It may not be at par but in many areas it is very close behind. At the time of liberation in 1949 it was as low as India and Pakistan if not lower on most indicators of development. It is not even endowed with such huge river basins like the Indus Basin of Pakistan. Yet today it is able to feed its 1.35 billion population without taking a begging bowl around.

The Chinese post-liberation history is divided into two nearly equal periods of 30-35 years each. During the first period, 1949-1978, educational and technical transformation occurred without the outside manifestation of development in the form of glamorous infrastructure, comfort in homes or urbanization. The Chinese made many breakthroughs and scientific innovations in the fields of nuclear and space technology, aeronautics, petroleum exploration, setting up steel, chemical, electromechanical, metallurgic, refining and consumer industry. People received their basic needs but their life remained simple and austere. The last ten years of this earlier period was the period of Cultural Revolution.

The next 35 years from 1978 onwards have been a period in which a different model of development was initiated under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. It was a period of reaping the fruit of earlier social investment. China now gradually changed course to a capitalist model of development in which production units started to be privatized, relations were monetized, work was incentivized, and people were encouraged to compete against each other. The capacity built during the earlier phase was now being reaped in the form of modern infrastructure, improved housing, cars and consumer goods. China today has become the workshop of the world. It is manufacturing most consumer goods used by millions of people all around the world, especially in the West. Such amazing production capacity has been achieved on the basis of social and human capacity transformation that took place in the earlier phase.

The last 10 years of this early revolutionary period, 1966-1976, were a period of great social and human transformation. It is this period of Cultural Revolution about which the book under review has been written.

Dongping Han, the author, grew up in Chinese village during the Cultural Revolution. In 1966, when the Cultural Revolution started, there were many illiterate people in his village. Many children would not go to school or would drop out after one or two years. During the educational reforms of the Cultural Revolution, villages set up their own primary schools and hired their own teachers. Every child could go to the village school or to the joint village middle school free of charge.

However, while Han was in college, the Cultural Revolution together with its educational reform was denounced by the government and the educational style and methodology disapproved.

In 1986 while teaching at Zhengzhou University Han had a chance to visit rural Henan where he was surprised many children could not read newspaper headlines because they were not in school. It was the same story everywhere he went. It could not be because of poverty. Why were children of villagers able to finish high school during the Cultural Revolution when ostensibly the rural areas were poorer than in 1986. He decided to study the issue.

In 1990 when he went to study in the History Department at the University of Vermont, he decided to write his thesis on the Cultural Revolution. He felt there was need to go beneath the surface structure of events that occurred at that time. After he entered the doctoral program at Brandeis University he continued his research on the same topic. For this he was to return to China a number of times to research in depth the evolution and consequences of educational policy and other changes during the Cultural Revolution.

Jimo County is where Han grew up. For his research he decided to study the history of a single county in depth in an effort to ground social science theory in the reality of people in a small place over time. He chose Jimo because he felt he could get at local knowledge best by going back into local society of which he had been a part, and where he had an intimate connection with the local people. Jimo County is on the eastern part of the Shandong Peninsula near the port city of Qingdao. It covers an area of 1780 square kilometers, and is composed of 30 townships (formerly communes) within these townships there are 1033 villages.

The context of the Cultural Revolution

The title of the book is apt. Of all the recent Chinese history the ten years 1966- 1976 of the Cultural Revolution remain the least known and misunderstood period. This was a period of intense struggle within the ruling Chinese Communist Party. In mid 1960s though Mao Tse Dong remained the Chairman of the party and commanded great respect throughout China and abroad, the Communist Party had split into two clear factions over the future direction of the revolution and party policy. Mao’s faction wanted to continue the revolution under the banner of class struggle both outside and within the Communist Party. The other faction led by Liu Shaoqi and later Deng Xiaoping considered it chaos and disruptive for production and development. They wanted to replace the engine of class struggle now with the engine of incentive. While Mao wanted to uplift the whole of Chinese society together by mobilizing the lowest classes to lead the revolution through the process of class struggle his opponents wanted to unleash the individual’s potential by providing economic incentive and breaking his bond with the much larger project of class or national uplift. The goal of national uplift was to be achieved by the much smaller project of the individual’s personal uplift. In the words of Adam Smith, the effort resulting from the greed of some, ultimately leads to the benefit of all. Deng Xiaoping summarized it well: “Let some people get rich first”. Mao called it the capitalist approach and its proponent’s capitalist roaders within the party.

The objectives of the Cultural Revolution

In 1966 the vast majority of Chinese people lived in rural areas and although the communist ideology considered urban proletariat as the vanguard Mao wanted the rural peasants to lead the revolution from behind. More concretely he defined closing the three gaps of the Chinese society as the aim of the next phase of the revolution. These three gaps were between ✓urban and rural areas, between ✓mental and manual labor and between ✓workers and farmers. It was easy to talk about them but to get serious about eliminating them meant trouble with the very party which had led the revolution in the previous phase.

Three major achievements of the revolution prior to 1966 had been liberation from imperialism, abolition of feudalism and the creation of collectives. These were no mean tasks and had taken off the burden of expropriation from the backs of the peasants and created conditions for accumulation of capital to undertake large scale projects in the rural areas.

However, from feudal domination the Chinese peasantry had now moved under the domination of the Communist Party hierarchy which gradually changed from being the voice of the people to assuming the role of a bureaucratic apparatus. Within the villages and the communes the Chinese peasants were still not fully liberated. He could not rise, rebel and freely air his views and say things out aloud fearlessly. The Cultural Revolution now aimed to do that.

The Cultural Revolution was not aimed at the old feudal and bourgeois elements. It was aimed at the new emerging bourgeoisie, the Communist Party local cadre and their patrons right up into the Central Committee. Mao believed people’s potential could only be realized if they could pick courage to rebel against their new oppressors many of which unfortunately happened to be the same local party leaders who had led their struggle against the feudal and the bureaucrat capitalists in the previous phase.

It was indeed essential to mobilize the people because the future of socialist China lay in the collective ownership structure, the communes, in the rural areas. The collective could not be successful without active participation and ownership of a liberated people. Such active participation, sense of ownership and mobilization could only be achieved through a democratic struggle leading to cultural equality.

In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution when masses and especially the youth were invited by Mao to rise and rebel against their class enemies the local Communist Party leaders successfully deflected their anger to the relicts of the old feudal and bourgeois classes who thus once again became the target of class hatred. The newly formed Red Guards under the local party leadership used the campaign attacking the Sijiu: (the four olds): ✓old thoughts, ✓old culture, ✓old traditions and ✓old habits to burn old books, old paintings, and destruction of old temples over several weeks. Many excesses were committed in this phase. It has become the dark side of the Cultural Revolution and has been projected as its principal character to condemn the Cultural Revolution as a whole.

It was in this situation that Mao presided over the drafting of the “16 points” in August 1966 which made a distinction between the Communist Party as an institution and the party bosses as individuals in a definitive manner and which stressed the target of the Cultural Revolution were the capitalist roaders inside the party. The old educated bourgeois classes and cultural heritage were not the target. The ‘chaos’ that attacks on local party leaders would cause was the price Mao was willing to pay in order to create opportunities to empower the masses. On many occasions Mao had to make more and more direct references to the target: “The enemy is within”, “Bombard the headquarters”.

Rural areas contribution to the Communist Victory

The Chinese Communist Party owed its survival and eventual victory in October 1949, to the rural poor. In the face of Chiang Kai-shek’s slaughter in 1927, a small and defeated Chinese Communist force was able to survive and grow quickly in the Jinggang Mountain region and other remote places because of the support of the rural poor.

In 1946, in order to mobilize the rural poor to join the Communist war effort against the Nationalists during the Chinese Civil War, the CCP sponsored the land reform in part of rural Jimo that was under its control.

But as the military situation shifted in favor of the Nationalists during the course of the Civil War, CCP forces retreated, and landlords who had fled returned to their hometowns with the Nationalist forces. With the support of the Nationalist forces some Jimo landlords organized small military groups, which villagers called “huan xiangtuan” or “returning home regiments.” They committed tremendous atrocities. Nie Yinhua, the head of the village Women’s Association, was only eighteen years old at the time. The landlords tortured her, then buried her alive. They sawed her palm with a string, and burned her breast with a gasoline lamp. In addition, Nie’s parents, grandfather, and two younger brothers were all killed. They killed Gu Xiuzhong, the head of the village Women’s Association, first. Then they killed her mother and three younger brothers and threw their bodies into a well. Her youngest brother was only eight years old at the time. The landlords held his legs and tore him apart before they threw him into the well.

In the final confrontation between the Communists and the Nationalists, the Communists were outnumbered, and their weaponry was inferior. The Nationalist army was armed with American weapons and had logistical support from U.S. Support of the rural people for the Communists changed the equation. They rushed to fill the ranks of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). They pushed wheelbarrows to transport supplies for the PLA and carried stretchers to take the wounded PLA soldiers to safety. In Shandong Province alone, several million peasants were on the road transporting supplies with wheelbarrows for the PLA during the Civil War.

1966: Situation on the eve of the Cultural Revolution

No doubt after the revolution the Communist Party fulfilled its promise of land reform and liberation of peasants from the oppression and serfdom of the feudal lords. Yet the peasantry continued to lag far behind the urban population. In the next phase through agricultural collectivization, the communists sought to promote production and improve the living standards of the rural residents through better organization and institution building. But these efforts were not enough to change the peasants’ relative position vis-a'-vis the urban population. Compared to urban residents, rural residents were still second-class citizens in China. The peasantry was still treated as stupid and ignorant xiangbalao (a derogatory term for rural residents) under Communist rule. Rural people’s incomes lagged behind those of the urban residents.

Urban workers enjoyed a much better diet and free medical care, and their family members could get fifty percent refund for their medical expenses from the state. Farmers had to pay for their own medical bills. There was no medical insurance in China’s rural areas and little access to modern medical care before the Cultural Revolution. Urban workers had paid holidays, weekends, paid sick days, insurance against injury and retirement pensions. Farmers had none of these benefits. The government rapidly expanded educational opportunities in urban areas. But in the rural areas like Jimo many rural children were denied a formal education for lack of space in schools.

Corruption and abuse of power became widespread among the rural Communist leaders soon after the CP came to power, even though CCP cadres were supposed to be different from the old type of officials, (for 1,000’s of years), they were supposed to be servants of the people.

In reality, the collectivization of the means of production did not transform everybody into equal owners of the collective, and did not empower the farmers politically or economically to the extent expected. The collectives pooled manpower, production and resources and assigned some to larger and common infrastructural projects, health, education and special needs like experimentation, which individual households could never dream of. But because the collective assigned work, determined wages and distributed grain it turned farmers into dependents of the collectives the same way it turned factory workers into dependents of modern industry. It created a management structure and concentrated authority in the local Communist Party cadre.

Prior to collectivization, village leaders’ power was limited. They were essentially managers of the public affairs in the village. Their basic functions were those of tax collectors and arbitrators of disputes among villagers. Collectivization gave village leaders more tantalizing power. When ordinary villagers who worked in the fields did not have enough to eat during the years of grain shortage following the Great Leap Forward, village leaders and their families were well-fed.

Rural Education: unfulfilled promises

Before the Communist Party came to power it had vigorously opposed educational inequality between urban and rural areas and proposed free universal education throughout China. At that time the fruits of the poor peasant’s labor enabled a small privileged group to enjoy the benefits of education. But that small privileged group then turned around to deceive and bully the rural poor, and to label them as ‘ignorant and stupid’.

The aim of the education had been social mobility and because of the rural urban gap parents educated their children with the hope they would ultimately leave the village for the power, comfort and culture of the urban upper classes.

Since few high school students returned to rural areas upon graduation high school education in rural Jimo made little direct contribution to rural development in the 17 years from 1949 to 1966. Instead of contributing to rural development, the educational system served as a drain on rural talent. Consequently, the countryside lacked the educated personnel capable of absorbing new knowledge and new techniques.

While the students’ success was measured by test scores, teachers’ success was measured by students’ success. After 7am to 5pm school, students were given heavy homework. Added to this crazy workload was parental pressure to bring glory to their family. There were frequent quizzes and tests and no time to play and exercise.

Historical data such as which emperor did what and when, mathematical formulas and language compositions and many other things needed to be memorized. Exposed to pressure to succeed and worried about failure from very early on in life the children endured a lot of mental stress but had little experience of real life. Creativity and imagination suffered. The struggle for success in examinations and fear of teachers and exams helped to create loyal and obedient civil servants not creative thinkers for society. A lot of this memorization was useless in later life.

The educational inequality between the rural and the urban areas after the revolution was justified by the beneficiaries of the urban key schools who argued that since there wasn’t enough money for all, some key schools must be kept if the nation was to compete in science and technology and keep its freedom. Mao and his supporters argued that only when vast majority of China’s rural people enjoyed adequate educational opportunity could China’s overall educational level be raised. So what was the revolution about if not about equality; somehow it didn’t occur to the Communist Party leadership.

Collectivization: Generating a new bureaucracy

Communism is first and foremost about sharing and collectivization. It is not about development through any means possible.

In the rural areas, the CCP’s first move after land reform in the early 1950s was to organize individual farmers into mutual aid groups and later into agricultural cooperatives. With better coordination, agricultural collectivization was supposed to make better use of the large pool of labor force in the countryside to improve the agricultural infrastructure, like soil improvement and huge irrigation projects. This labor force could not be mobilized without collective ownership.

Communes pooled resources from production brigades to invest in industrial enterprises and engage in gigantic irrigation projects for the benefit of an entire commune. With the improvement of the agricultural infrastructure, farmers were less dependent on rainfall for a good harvest, and production was expected to increase greatly.

Consequent upon the formation of rural communes 1958-1961 were the years of the Great Leap Forward, a crash program initiated by Mao Tse Dong for the creation of widespread agricultural infrastructure and industry in the rural areas under local initiative. The very success of the program in building agricultural infrastructure and setting up industry in rural areas under local initiative meant large scale diversion of infrastructural capital formation and as a result production of food suffered. It was compounded by a severe drought during the same years. Opponents of Mao’s radical initiative in the Communist Party used the situations to dismantle the communes and roll back the spread of rural industry.

Rural industry was nonexistent in Jimo before 1958. With the establishment of the communes, farmers set up many industrial projects with very little capital. Two thousand eight hundred and fifty-four enterprises had been set up by August 1959, employing a total of 47,932 people.

Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping's readjustment policy following the failure of the Great Leap Forward closed down the new rural industrial enterprises. Only ten rural enterprises (10 out of 2,854), in Jimo survived the initial readjustment. These ten enterprises employed only 253 people and their annual output was estimated at only 170,000 yuan. By 1963, all commune-run industrial enterprises came to a stop.

Communes not only helped create large scale capital projects but also substantial social security guarantees were enabled by the collective distribution system in Jimo. No matter whether a villager could work or not, the collective undertook to provide him and his family with “five guarantees”, (wu bao) - food, clothes, fuel, education for his children and a funeral upon death.

Seventy percent of the collective harvest was divided on a per capita basis, and only thirty percent of total production was divided according to the input of labor. In the short run, those who contributed more labor to the collective seemed to be shortchanged.

The main weakness of rural collective organizations was political: ordinary members were not politically empowered and were dependent on village and commune officials. The Communists had not fundamentally changed the rural political culture of submission to authority and had not significantly remedied the lack of education in the countryside.

Criticizing a sacred cow: Cultural Revolution and political empowerment

The Communist Party had fought and given supreme sacrifice for the cause of the people. So, after the revolution no one was better qualified to lead the people. The Communist Party thus was granted the supreme authority by the Chinese Constitution to rule. But without appropriate supervision from the people, the party bosses at all levels possessed the human tendency to become arrogant and corrupt. The corruption of an increasing number of individual party leaders would eventually lead to corruption of the party as an institution – from a quantitative change to qualitative change.

If the revolution was not to be taken over by a bureaucratic apparatus, increasing the marginalization of the people with eventual restoration of capitalism the new emerging bourgeoisie within the ranks of the Communist Party had to be confronted and defeated giving a boost to the power of the masses in the process.

The power of the old ruling class stood discontinued but their cultural hegemony continued in many ways and they had powerful external backers. The party leadership thus needed to be protected and so had often been presented as a “sacred cow” by CCP leaders at various levels. This by itself led to many distortions. Challenges to their personal authority and criticism of the mistakes of party leaders could be labeled “anti-party,” and challengers subjected to severe punishment. Party committees and their work teams continued to use this mechanism to suppress challengers during the early phase of the Cultural Revolution. In other words, official work teams, sent out by party authorities in the name of leading the Cultural Revolution, were used to suppress the very activity – independent criticism of Party authorities – that Mao was trying to encourage by launching the movement.

In some other ways, the opening stanza of the Cultural Revolution in Jimo also looked like a second land reform because the traditional enemies of the Chinese Revolution – former landlords, capitalists and rich peasants – were again targeted. In order to deflect criticism of their own behavior, local party officials encouraged renewed attacks against the old class enemies.

Of course, from the point of view of local party officials, campaign the official Red Guards’ was to destroy the four olds and attack on former landlords, capitalists and political enemies were convenient ways to divert attention from themselves and protect themselves from attack.

It was in this situation that Mao presided over the drafting of the “16 Points” in August 1966, which made the distinction between the Communist Party as an institution and party bosses as individuals in a definitive manner, and which stressed that the targets of the Cultural Revolution were the capitalist roaders inside the party.

Strategies adopted by people to criticize the corrupt cadre

Mass associations and political empowerment

Before the Cultural Revolution for ordinary villagers there were no channels to air their grievances. Their expression therefore was violent whenever happened. After the Cultural Revolution villagers no longer felt shorter before the village party leaders.

In the past people were made to bribe the party officials, they suspected embezzlements and foul play but they did not question for fear of reprisal. With the start of the Cultural Revolution the big character posters appeared as one strategic tool which gave them courage to know and raise these issues.

Big character posters, debate and political empowerment

The big character posters were a simple but ingenious device to promote free expression. Whoever wanted to criticize or raise a question didn’t have to do it in person. He/she could just write a big character poster or get it written and put it up in the village. Big character posters more than made up for the absence of a free press while the ordinary people were empowered the party bosses hated it. Even if you had nothing important to say it created a habit of speaking your mind.

Big character posters which expose and challenge local practice and authority are far more potent and effective in a local area like a village, than in a larger setting like a district, province or a country. In a village they can threaten and change the power relations.

Chuanlian and political empowerment

Chuanlian was the term for the students and young peoples’ journey to and from Beijing to learn from Beijing and other places on the way.

In Jimo County, the Cultural Revolution took a dramatic turn after young people returned from trips to Beijing where they gained new perspectives. The independent mass associations emerged, and destruction of the sijiu (four olds) based on wrong interpretation stopped.

In 1966, one group of twenty rural youth between fourteen and sixteen years old left their rural middle school in Jimo County on foot for Beijing. At reception centers on the way they met students from other places and discussed the developments of the Cultural Revolution with them. They read and copied big character posters. They collected and read large quantities of the political pamphlets published by different Red Guard associations in cities and towns. As they saw the world, and exchanged ideas with others, they felt politically empowered.

In Beijing and in other cities along the road to Beijing they had some eye opening experiences. The school classrooms in the cities were much better equipped than those in their own school. They had glass windows, electric lights, and better desks and chairs. The city people ate mostly wheat flour breads, with vegetable and meat dishes. Back home their families grew wheat and raised pigs and poultry. But not just wheat flour and meat were luxuries, even most vegetables were too much of a luxury for them.

The outrages of village tuhuangdi (local emperors), the villagers’ term for the unaccountable corrupt local leaders, who stole collective grain, slept with other people’s wives and suppressed those who dared to challenge them angered the Jimo high school rebels and fired their determination to sustain the Cultural Revolution.

The campaign to study Mao’s works and use his words for political empowerment

Mao’s books became available and directives from Mao and Central Govt were read and explained to villagers much against the dominant traditional philosophy that “ordinary people should be lead but kept ignorant”. Mao’s writing and his words started to be used in a variety of ways to bulldoze the local corrupt party leaders and demolish their bureaucratic ways.

For the educated elite today, songs based on Mao’s quotations and a banxi constitute a personality culture. But ordinary villagers used Mao’s words to promote their own interest. Mao’s works had become a de facto constitution for rural people and his words became an important political weapon for ordinary villagers. They used Mao’s words in their debates with abusive village leaders.

Mao’s essay “Serve the People,” one of the three essays, people were encouraged to memorize during the Cultural Revolution, is less than three pages long, but it contains several straightforward messages. First, it states that the CCP and the People’s Army have no other goal than to serve the people. This message undermines the legitimacy of selfish and corrupt behavior on the part of officials. Second, it states that the CCP and CCP officials should not be afraid of criticism, and if the criticism is correct, they should accept it and act on it. On the one hand, this principle provided ordinary villagers with the right to criticize their superiors. If a leader was afraid of criticism and forbade people to criticize him, he was unqualified to lead the masses. Third, it says that everyone in the revolutionary ranks is equal regardless of rank or position. Implicitly, this criterion denounced all practices of beating and cursing by village leaders and other officials. Today farmers still say that “Chairman Mao said what ordinary villagers wanted to say” (shuo chu liao nongmin de xinli hua).

Rural education reforms during the cultural revolution

Education is normally not considered part of the political process but it happened to be, deeply so. No wonder it was the most contested terrain of the Cultural Revolution.

Challenging the Jimo education system

The rebels raised specific questions about how the school should be run. What should be the admissions policy? What kind of teaching materials should be used? And what kind of students should be produced? They challenged the system because they felt it contradicted the ideological belief in social equality with which they had been indoctrinated by the Communist Party.

The challengers demanded an overhaul of the existing educational system to make it open to the disadvantaged segments of Chinese society, children of the so-called poor and middle peasants and the workers. Since the beginning of the Great Leap Forward, the Chinese Government had been talking about eliminating the three gaps: between urban and rural areas between mental and manual labor, and between workers and farmers. For the eighty percent of the Chinese population living in rural areas, the slogan of eliminating these gaps was very powerful and appealing. But a slogan was only a slogan. It was only during the Cultural Revolution that some students took it so seriously that they adopted it as a concrete goal of their struggle. They believed that the government’s educational policy, instead of helping eliminate these gaps, was actually perpetuating them. They saw with their own eyes that a very small number of educated youngsters from elite middle schools entered college and never returned. Those high school graduates who did not enter college became government employees and urban workers; few ever came back to the rural areas.

Village schools operated on a flexible schedule. During the busy season, teachers would take students to the fields to help with the harvesting in whatever ways they could, like gleaning wheat fields, or sometimes singing songs for villagers at breaks.

Jimo’s experimental village primary schools during the Cultural Revolution offered solutions to the various problems that had caused many children not to attend school. First of all, it provided enough school space for every child in the village. There was no need to reject any child for lack of space. Second, the school was free. Parents did not need to pay tuition for their children’s education. Third, children went to school in their own village and school hours were flexible, which meant children could have more time to help their parents with household chores. During busy seasons when parents needed their children’s help most, the school was closed.

The enrollment of school aged children in Jimo County reached 90.5 percent in 1968, 98.3 percent in 1973, and 99.1 percent in 1976. Between 1969 and 1976 (7 years) high schools increased from 17 to 84 and enrolment from 3,020 to 13,172. From 1969 to 1976 there were 19,130 high school graduates 13 times more than in the 17 years before the Cultural Revolution. An entrance examination was not needed to keep anybody out.

Combining education with productive labor

The old curricula and text books were divorced from the real lives of rural children and put rural children at a disadvantage. The math, physics and chemistry text books had little relevance for daily life, while concepts and formulae useful for rural life were not taught.

What constitutes good education? A more rounded education which in Jimo context combined academic study with some industrial and farming skills. Jimo Teachers Training School students rotated working in school’s plastic workshop and vegetable garden, 3 hours a week. Students and teachers from Jimo number one Middle School spent three months in different factories and compiled text books on the operating principles of internal combustion engines, crops, fertilizers and farming machines. Over time schools also set up their own workshops and farms to experiment and to generate income.

Apart from opening the school doors wide to rural children a farmer teacher of South River joint Middle School cited 3 major achievements of the educational reform during the Cultural Revolution. ✓First rural schools trained members of local youth in practical industrial and agricultural skills and knowledge which had long term impact on the development of rural areas. ✓Second, the education debate began to alter the views of teachers who had previously looked down upon farmers. ✓Third, the struggle empowered villagers. Farmers no longer viewed the educated elite with mystic feelings after having worked with them. The educational reforms during the Cultural Revolution served the historical needs of the rural areas extremely well.

Many teachers began to encourage students to ask questions in the classroom, and to engage in discussion among themselves and with teachers. Some teachers made extra efforts to involve students in preparing new lessons.

Educated youth in the countryside

Instead of educating the rural population, the pre-Cultural Revolution educational system was depleting the countryside of talent. The few students who were able to attend high school went on to college or got a job in the city. Few ever returned to the villages.

In June 1966 institutions of higher education suspended the scheduled national entrance examinations. From the perspective of the advantaged individual, it was dream-shattering, but from the perspective of rural development, it was like a blood transfusion to a sick person and brought knowledge and skills that revived rural areas. Going to college immediately after high school graduation was no longer an option. Every student had to work in a rural area or in a factory for at least two years before becoming eligible for college. Academic performance was not the sole criterion for the selection of candidates for college. Students had also to prove themselves good workers or farmers before going to college. Starting in 1976 college students from rural areas were required to go back to their original villages after graduation to serve the villages that sent them to college. The Shangshan Xiaxiang (going up the mountains and down to villages) movement was intensified following the suspension of college entrance examinations. The graduating high school students returned to their home villages. Even high school graduates with urban hukou (household registration) went to settle down in rural communes. Most stayed there for two years before they got jobs in town. The influx of educated youth of both rural and urban origin, into rural areas changed he educational structure and talent base of the rural population. These students became the new teachers, medical personnel, and skilled workers and technicians on which rural development depended. The movement of encouraging educated rural and urban youth to go to the rural areas restored the ecological closed cycle of the Chinese education.

From the perspective of the village, the Cultural Revolution decade, far from being a disaster for education, as it is routinely presented by Chinese education officials today, it was period of unprecedented development.

Development model and achievements of the Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution decade agricultural production more than doubled in Jimo county. At the same time, rural industry, which had been negligible before 1966, grew to become nearly 36% of the Jimo economy.

The author argues that two key factors were products of the Cultural Revolution—a change in political culture, which empowered ordinary villagers and enhanced collective organization and rapid improvement in education, which provided literacy, numeracy and technical knowledge that made the adoption of modern technique possible. In the new political culture of the Cultural Revolution decade political campaigns remained an important component. The Cultural Revolution consolidated the collective economy. The “socialist” line of development was promoted and contrasted with so-called “bourgeois” line of development. In rural Jimo, the “socialist” line of development was understood to mean cultivating and encouraging loyalty to the collective.

In 1968, the South River Production Brigade began a major irrigation project. During the day, a special group of people worked on the project. At night, villagers who worked on other projects during the day all came out to put in a couple hours of work. During the crucial stage of the project, schoolteachers, students, and local government employees all came to help. They worked from 7:00 p.m to 10:00 p.m. each day for several days until the crucial stage was completed. While the villagers got paid in work points and would benefit directly from the irrigation project, government employees’ and school teachers’ neither got work points nor direct benefit. Nevertheless, they volunteered to work on the project at night.

Second, the education reforms led to the adoption of more practical curricula tailored to the local needs. School children learned agricultural, mechanical and industrial skills in school, which they could make good use of upon their return to their villages. Village middle schools and commune high schools quickly trained thousands of rural youths with technical know-how.

The changing political culture together with rural educational reforms broadened villagers’ minds and horizons. They began testing new farming methods and new crop seeds. In 1966, 244 of 1,016 production brigades in Jimo set up experimental teams to cultivate new seeds, and test new farming methods. By 1972, the number of experimental teams had increased to 695, employing 4,043 people, and by 1974, the figure had increased to 851. At the same time, about 1,015 production teams, (industry), had set up experimental groups.

The average total unit yield in Jimo county was 69.1 kilos in the period between 1949 to 1965. Grain production per mu of land in 1976 reached 180 kilos, 2.16 times that of 1965. In the early 1960s, in the entire Jimo county there were only ten rural industrial enterprises which together employed only 253 people.

By 1976, there were 2,557 rural industrial enterprises in Jimo with an average of 2.5 enterprises per village. These rural industrial enterprises employed a total of 54,771 people and annual output amounted to 91,360,000 yuan (1970 constant value). By then, rural industry accounted for 35.8 percent of the total income of the thirty communes in rural Jimo.

While incomes of rural Jimo residents rose substantially during the Cultural Revolution decade, the incomes of urban residents in the town of Jimo stagnated or actually fell. The average annual income of a worker in a state-run factory in Jimo decreased from 480.7 yuan in 1956 to 427.8 yuan in 1976. If a state worker had four dependents to support, then his family per capita income in 1976 would have been 85.4 yuan, only a little higher than a typical peasant family’s per capita income.

This fact coupled with the significant increase in rural incomes, however, led to a closing of the gap between urban and rural living standards, a communist goal that Mao particularly emphasized during the Cultural Revolution.

Medical care comes to rural Jimo

Before the Cultural Revolution there was a general lack of medical care in the rural areas and care of the sick was a responsibility of the family. Many families hated to go to the County People’s Hospitals. The fee was too high and they could not stand the arrogant attitudes and careless handling of the doctors and nurses in the hospitals.

The reintroduction of collectivization during the Cultural Revolution introduced “Barefoot doctors” in the rural areas. The rural barefoot who staffed village clinics were mostly returned educated rural youth, who had received rudimentary medical training sometimes as internees during their high school years. Each village then sent two or three young people to receive regular medical training. The barefoot doctors then provided villagers free medical care. In case a villager needed to be hospitalized at the county hospital the village would pay for his medical bills. If the bills were too big for the village and the commune; the hospital would waive it. The barefoot doctors were paid for by the local collective the same wage as the other peasants.

The value of the barefoot doctors cannot simply be measured by the formal training they received. They were from the same village as their patients. They were available 24 hours a day in all weather conditions, even during the Chinese New Year or during a big snowstorm. Their medical training was adequate to treat common problems and for bigger problems they would get help from regular doctors from the commune or the county hospitals. Life expectancy in Jimo County increased from 35 years in 1949 to 70.54 year in 1986. This healthcare system was made possible only by collectivization.

Reversing the Cultural Revolution

Political empowerment is a long process. In China, where officialdom had been dominant for thousands of years, this process, of necessity, was not only long but tortuous. The Cultural Revolution was one of the first attempts to empower ordinary rural Chinese against officialdom. It only succeeded to a limited extent. The complete negation of the Cultural Revolution following 1978 was like a quick deep frost on tender spring crops. It rolled back and, in many respects, destroyed the process of political empowerment in China—at least this seemed to be the case for rural Jimo.

The emerging democratic culture of da ming, da fang, da bianlun and dazibao (great airing of opinions, great freedom, great debate and big character posters) of the Cultural Revolution empowered the rebels and ordinary people. They began to challenge aspects of China’s traditional culture of officialdom, demanding that party leaders conform to the ascetic Maoist code of official conduct.

However, the political situation in China changed rapidly following Mao’s death. Following the arrest of the ‘Gang of Four’ at the center, old party officials at different levels of government around the country rounded up former rebel leaders. In Luoyang, an industrial city in Henan Province, for instance, hundreds of former rebel leaders were arrested and paraded in public and then disappeared. Farmers referred to these acts as the new Huan Xiangtuan (the returning home regiments) a title they had given to the revengeful military bands of the landlords against the peasants who had taken part in the land reform movement during the civil war. In the early 1980s, the government mounted an even larger and more extensive campaign of retaliation against the former rebels. Government departments, factories, schools, universities, research institutions all set up special offices to investigate charges against former rebels.

Deng Xiaoping promoted the changzhang fuzezhi (manager responsibility) system, which put all authority in the hands of the managers. Under the new system, managers decided how much they would get paid and how much workers would get paid. They could dispose of public assets without being accountable to anybody.

And now while many enterprises cannot even find funds to pay workers, managers are getting fatter and fatter with their control of state resources. Press accounts have dubbed this phenomenon: “qing miao fu fangzhang” (poor temples with wealthy abbots).

Dismantling the Collective Organization

The “household responsibility system,” which was promoted by the Central Government in the early 1980s, was considered by many to be a reactionary measure imposed on Jimo farmers. Villagers said: “xinxin kuku sanshi nian, yi yie huidao jiefang qian” (we worked hard for thirty years to build up the collectives, but overnight we returned to the status quo before the liberation). Many farmers in Jimo did not want to change their way of life. In fact, they were shocked by the government decision to disband the collectives on which important rural social security measures, education, and medical care depended.

Government officials all enjoy job security, medical insurance, and retirement pensions, and their children have easy access to education. They take these things for granted. But they never put themselves in the farmers’ shoes. Before they were disbanded, collectives had become an important institution in rural life. Job security, medical insurance, old age safeguards and education in rural areas had all been built around this one institution.

Before Deng Xiaoping’s rural reforms, Jimo’s rural industrial enterprises were all owned and operated by the collectives. Workers in these industrial enterprises were paid in work points, the same way as farmers working in the fields and profits from these enterprises were distributed among farmers the same way crops were distributed. Managers and village party secretaries were paid the same amount of work points for a day’s work as ordinary villagers. It was a very equitable system.

But with the division of land, the collectives did not exist anymore. Management of these industrial enterprises were left in the hands of village party secretaries and the managers of the collective industrial enterprises. Frequently, these collective enterprises were rented to their managers for fixed rents decided by village party secretaries and managers of the collective industrial enterprises themselves. South River village, for example, rented its collective enterprises to the managers, Zhao Licheng and Guan Dunxiao, after 1984 for a fixed amount. In some other villages, the enterprises were sold to the managers. Despite the strong resistance of villagers, Yaotou Village sold its village enterprise to its managers.

This practice changed the nature of rural industrial enterprises. Whether through renting or outright buying, the managers took complete control of the formerly collective enterprises. They had the right to hire or fire workers and to decide how much to pay workers. Workers lost their job security, medical insurance and job-related injury compensation. The managers of South River Village enterprises gradually replaced most village workers with outside workers.

The power relationship in the rural areas was reshuffled by the dissolution of the collective. Unlike during the collective years when villagers worked together and shared common bonds because of their collective interests, villagers are now fragmented by issues concerning their own families as they farm their land separately. The division of land eliminated the production team leaders – the most important check on village party secretaries – and also fragmented the village population, concentrating power in the hands of the village party secretaries.

The decline of rural education

After 1978, the Central Government denounced the educational reforms introduced during the Cultural Revolution. Key schools at various levels were again established and resources were channeled to these key schools, which cater largely to the advantaged segments of urban Chinese society. Many rural schools, especially middle schools and high schools, were eliminated in the name of streamlining and quality control.

Rural education had largely been supported by the collective structure. Village schoolteachers were paid in work points the same way as villagers working in the fields. The burden of financing rural education thus was born collectively by the community. With the dissolution of china’s rural collectives, rural teachers had to be supported by tuition, and the costs of education are now borne by those who go to school. Most villages have little resources to support village schools.

During the Cultural Revolution decade, 98.5 percent school-age children in Jimo were in primary school, 90 percent were in middle school and over 70 percent were in high school.

Rising tuition, the remote location of the remaining schools and the demands of family farming caused many rural families to decline to send their children to school. Rural middle and high school education suffered most as a result of the rural reforms. The number of middle schools in Jimo decreased from 256 in 1976 to 106 in 1987. Many joint village middle schools were eliminated, because villages no longer had the resources to support the schools. The size of the middle school first year class dropped from 29,660 in 1976 to 15,734 in 1987. The number of high schools dropped from eighty-nine in 1977 to eight in 1987.

In 1977, the national college entrance examination was reintroduced and since then it has once again systematically drained talent from China’s rural areas, in the same manner as before the Cultural Revolution. Talented rural children leave home to go to college and few return. The educational reforms of the Cultural Revolution had made serious effort to link education with the needs of rural Jimo. The reinstitution of the college entrance examination system once again fundamentally changed the nature of rural high schools. Instead of being oriented to serve rural development, schools became an avenue to joining the urban elite.

The reinstitution of the college entrance examination had ramifications in other areas of rural life. As soon as the national entrance examination resumed, textbooks had to be standardized nationally, since students had to sit for the same examination. Since national standard textbooks are compiled mostly by experts from urban areas, local knowledge relevant to agriculture and rural development were scarified.

The divorce of school curriculum from rural life has put rural children in a disadvantaged position because it is harder to study subjects that have no connection with their lives. This in turn has also contributed to the change of orientation of education for rural children. For each individual family, education is a big investment. The family has to pay for the children’s tuition, books, and other costs.

There is great pressure on the schools to pay more attention to only the brightest children who have the greatest potential to succeed in the examination. Thus in order to achieve high success rates in the college entrance examination, schools and teacher often devote their energy to preparing the better students for the college entrance examination while ignoring the needs of other students.

The collapse of the rural medical care system and the “five guarantees”

The rural medical care system has suffered a fate similar to that of rural education. In 1983, after the collectives were dissolved, barefoot doctors in rural Jimo were renamed “rural doctors”. Their service was no longer free, since the collective organization that supported these doctors was no longer there and they could no longer be paid in work points. Village clinics became private medical practices. Villagers who fell ill and used the services of rural doctors had to pay the bills. The community medical insurance that was part of the previous barefoot doctor system was eliminated, so each rural family was left on their own.

The “five guarantees” (wu bao) – food, clothes, fuel, education and a funeral – the collective had provided for old villagers and others who had no other support also disappeared with the dissolution of the collective. The economic foundation for the five guarantees had disappeared. Jimo farmers had never had formal pensions, as urban workers did. When the collective disappeared in 1983, many farmers who had worked for the collective for 25 years during their prime years found themselves having to depend on themselves for everything in their old age.

There are only a few cases of childless villagers in each of Jimo’s village, but their difficulties serve as a warning for other villagers. Witnessing the plight of these childless old folks, some farmers have defied the government’s one-child policy and continued to have two or three children. They want to have at least one, better two, male children, not just to continue the family line but as security for their old age. What if something happens to their only male child? Jimo farmers have learned from their experiences that nothing provides a better economic security for old age than their own flesh and blood, and the removal of collective guarantees has prompted them to accentuate this safeguard.

If the government does not provide farmers any security, farmers will have no other choice but to find their own security. This is why despite the extreme family planning measures in the rural areas, including cutting off supplies of electricity and water, dismantling houses, heavy fines and physical punishment, Chinese farmers continue to have more than one child. Farmers’ desire to have more children under today’s private farming is completely justified.

Assessing the Cultural Revolution

It is common belief that rapid economic growth in rural China began with the political ascendancy of Deng Xiaoping in 1978 and the ensuing market reforms. It is also believed that the Cultural Revolution was an economic disaster, which resulted from an overemphasis on the collective economy, vengeful political campaigns that persecuted party officials and intellectuals, contempt for educational standards and institutions, and an overzealous pursuit of egalitarian goals. Han’s meticulous investigation of the history of Jimo County has definitely challenged this official account.

Rural transformation could not have taken place in China without the role of communes. But one of the author’s central arguments is that a collective economy becomes dysfunctional without a democratic political culture and institutions that empower ordinary farmers and workers. This is as much true of a commune as of a joint family, a community or of state. The Chinese Communist Party was able to transform the ownership of the land and other means of production in China in the course of a few years. The transformation of political culture proved to be a more intractable problem.

The Cultural Revolution was an attempt to address this problem. It was an intensive and extensive social revolution aimed at changing people’s social consciousness, the parallel of which is hard to find in history. It attempted to enhance collective organization by challenging autocratic political authority within the collective. Big character posters widely used by villagers proved to be an important medium of political communication between villagers and village leaders. The mass associations, public debate and mass meetings provided important public forums to put matters of public interests onto the agenda. The political culture in the rural area was significantly changed. Farmers were no longer timid, submissive as they used to be. They were empowered by the experience of the Cultural Revolution to constantly keep village leaders in line. Social vices like official corruption, prostitution, drug abuse, fake products and others that plague Chinese society today were completely absent at the end of the Cultural Revolution.

As soon as Deng Xiaoping came back to power, he denounced the Cultural Revolution and reversed its reforms. Deng had the power to do whatever he wanted. But more important, he was supported by the persistence of traditional philosophies and practices that had been challenged during the Cultural Revolution, and by people who stood to benefit by the restoration of the old way, or thought they would.

One of the first things Deng Xiaoping did was to outlaw the sida (big character posters, the great debate, the great airing and great political freedom). He also announced that there would be no more political campaigns, which was giving the officials a guarantee that they would not be harassed by the masses even though they were corrupt. Many officials slipped into their corrupt old ways very quickly.

During the ten years of Cultural Revolution the Chinese peasants and the workers had waged their struggle at the local level. They had found support and encouragement from Mao representing the central level of the Communist Party. At the end of the Cultural Revolution the battle was lost not at the local level but at the central level. They had always loved and respected the central party. It was difficult for them now to take a stand against the central level of the Communist Party.

As soon as the political climate changed, officials ceased to participate in physical work with farmers, and they began to look after their own families. They found their children better jobs, and put them in important positions. That was how the present official corruption started in China since the reform.

Deng revived the old education philosophy. Education reforms introduced during the cultural Revolution were wiped out overnight. He was supported by an educated elite who clung to the old educational philosophy and practices.

Confucian ideas that a good education should pave the way for an official career, and that schooling is above everything else, and have proven very resilient. Many old intellectuals did not like the idea that the educated should interact with society. Many farmers and workers also cherished the idea that their children might one day become members of the elite through education. Therefore, Deng’s denunciation of the Cultural Revolution’s educational reform initially struck a responsive chord among these elite people.

The official evaluation of the Cultural Revolution serves to underline the idea, currently very much in vogue around the world, that efforts to achieve development and efforts to attain social equality are contradictory. The remarkable currency of this idea in China and internationally is due, at least in part, to the fact that such an idea is so convenient to those threatened by other’s efforts to attain social equality. This study of the history of Jimo County has challenged this idea. During the Cultural Revolution decade and in the two decades of market reform that followed, Jimo experienced alternative paths, both of which led to rural development. The difference in the paths was not between development and stagnation but rather between different kinds of development. The main conclusion the author hopes readers will draw from the experience of Jimo County during the Cultural Revolution decade is that measures to empower and educate people at the bottom of society can also serve the goal of economic development. It is not necessary to choose between pursuing social equality and pursuing economic development. The choice is whether or not to pursue social equality. Grass root democratic political culture and institutions that empower ordinary farmers and workers lift the whole people and the whole economy.

.