The Greatness and Fall of Ancient Tibet (part 2)

Lev Nikolayevich Gumilev, 1969 – (about 15,000 words, in two parts)

A continual power struggle was mirrored in the development and abandonment of Buddhism, many many times. In a way, this story is very similar to the Three Kingdoms of China, in that it is total dictatorial disaster of 100’s of years. There were indeed external wars, but the use of religion among the elites amounted to a long running civil war. The Tibetans destroyed themselves.

THE WAR FOR TOGON

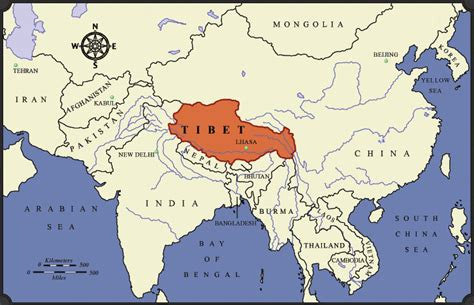

The most acute problem facing Tibet was the relationship with the Tang Empire. The interests of both great powers were directly opposite. It should be taken into account that Tibet in the VII century. it was locked from all sides. In the west stood the unconquered Dards; India was protected not so much by the Himalayas as by the climate, deadly for the inhabitants of the harsh highlands; in the north lay an impassable desert, and in the east — the most powerful world military power — Tang China. The only way out was to the northeast, through Amdo to Gansu, and to the expanses of the Hexi steppes and the "Western Edge" (Xinjiang). But this exit was blocked by the Togon Kingdom, although weakened, but strengthened by the patronage of China.

If it was necessary for Tibet to master Togon, it was no less necessary for China to prevent this. The victory over the Turkyuts, which was not cheap, could be nullified by the appearance of an anti-Chinese center of attraction in the steppe, as the nomads raved about rebellion and independence. Having escaped to the steppe, the Tibetans could cut off Chinese communications and, relying on rebellious elements among the Turkic tribes, drive the Chinese back behind the Great Wall. Therefore, the Chinese provided all possible assistance to Togon, despite the fact that this entailed a war. And in Togon itself, the alliance with China was extremely unpopular. The long-term wars with Zhou, Sui and, finally, Tang China could not pass without a trace.

The Chinese responded to the Togon raids with disastrous invasions, flooding Amdo with Turkuts, Uighurs and other allied troops. The final victory remained with China, but Tai-tsung's henchman, the well-known prince Muyun Shun, despite Chinese support, was killed by his subjects.[68] Tai-tsung installed on the khan's throne the son of the murdered Muyun Shun, a minor Nohebo, completely devoted to China. Nohebo introduced the Chinese calendar in Togon, married a Chinese princess, and sent young Togonians to Chang'an to serve at court. Naturally, the opposition that arose focused on Tibet, but the conspiracy of 641 it was disclosed and liquidated.[69]

The firm policy of Tai-tsung and the sharp turn of the Tibetan orientation under Srontsangambo secured Togon for a while, but when Dongtsang resumed the offensive to the east, and the short-sighted Gao-tsung refused Nohebo immediate help, the fate of Togon was decided.

The Togon nobleman Sodohui fled to Tibet and informed Dontsan of Gao-tsung's decision; Dontsan immediately started a war and in 663 completely defeated the Togonians at the upper reaches of the Yellow River.[70] Nohebo with the princess and several thousand caravans fled to Liangzhou — under the protection of China. Gao-tsung caught himself and sent an army to Togon, putting Su Ding-fan,[71] the hero of the western campaign against the last unconquered Turkuts, at the head of it, but it was too late. It was hard to imagine a less fortunate set of circumstances for the Tang Empire.

The cautious Dongtsang tried to negotiate with Gao-tsung, but his proposals for the division of Togon were rejected. Dongtsang died, leaving four sons who were not inferior to their father in their abilities; the eldest, Qinling,[72] became a "great adviser", and the younger ones led the troops, and the war began. The Imperial government found itself in an extremely difficult situation, since the best troops were engaged in Korea, the conquest of which was completed only in 668.[73] During this time, the Tibetans "defeated 12 Chinese regions inhabited by the Kyans",[74] and strengthened their army at the expense of the attached Dansyans (Tanguts) and choirs (Togonets). Around 670, the Tibetan army broke into the Tarim basin and, relying on the sympathy of the Turkuts and the alliance with Khotan, destroyed the walls of the Heap, as a result of which the entire "Western Region", except Xi-Zhou (Turfan), was in the power of the Tibetans.[75]

In an effort to regain what they had lost, the Chinese moved a large army to Tibet, but at Bukhain Gol [76] they were completely defeated. The Chinese commander Xie Jin-gui made peace with the Tibetans and only on this condition was able to retreat in 670. Another army sent against the Tibetans returned from the road because of his death, and this ended the first stage of the war. The Tibetans twice offered peace to the Tang Empire — in 672 and in 675, but Gao-tsung rejected these proposals, and in 676 the war resumed.”

THE TIBETO-CHINESE WAR FOR THE WESTERN EDGE

The intensification of anti-Chinese sentiments among Western and Eastern Turks in 679 was associated with the vicissitudes of the Tibeto-Chinese war, which reached its climax at that time. The Chinese government perfectly understood that there would be no order in the steppe until the Tibetans were driven back into the mountains. A huge army (180 thousand people) was sent for this purpose,[77] and it was headed by the "secretary of state" Li Jin-xuan, an educated and cunning Chinese, but who did not possess any military talents.

The Chinese chronicler even attributes the main role in this appointment to the evil will of Li Jin-xuan's rival Xie Jin-gui, who wanted to doom a competitor to defeat and royal disgrace.

At first, the Chinese were successful, but near Lake Kukunor they were surrounded by Tibetans. The Chinese vanguard, which broke away from the bulk of the troops, was exterminated, and the army itself was pressed against the mountains and blocked. The only thing that saved the Chinese from death was a bold night attack by Hechi Chang-ji, a Korean by origin; he was an athlete of high stature and unstoppable courage,[78] one of those "ilohe" (daredevils) who were attracted and cherished by Tai-tsung. At the head of 500 selected fighters, he wedged himself into the Tibetan camp, raised panic among the enemies and punched a gap in the blockade, through which the remnants of the recently formidable army fled.

In desperation, Gao-tsung called a council to decide what to do with the Tibetans, but the opinions of the courtiers were divided, and the council did not take any decisions — the Tibetan threat was already hanging over China itself. In the same year, 679, Manromanzan ("nameless") died, and his eight-year-old son, Dudsron, was elevated to the throne,[79] under whom Qinling and his brothers retained full power.

In 680, the Tibetans invaded China and inflicted a "perfect defeat" on Li Jin-xuan, but Hechi Chang-zhi with three thousand selected "cutting cavalry" (thu-ki) attacked the Tibetan camp at night and forced the Tibetans to retreat. Appointed after this victory as the head of the border line, Hechi Chang-ji built 70 signal points on the border and established government fields to supply the border troops with bread, but despite this, the Tibetans, with the help of border kyans,[80] broke through the defense line, entered Yunnan and subdued the semi-wild forest tribes known as Manei.[81]

The following year (681), the Tibetan commander Tsanbu, brother of Qinling, tried to break into inner China. Although it was repelled by Hechi Chang-ji, but it was a defensive success that did not lead the Chinese out of a situation that was becoming disastrous. It worsened even more in 689, when the Chinese troops stationed in the "Western Region" were defeated by the Tibetans. The Chinese government panicked and was ready to abandon the "Western Edge",[82] but the historiographer Cui-yun presented a report in which he proved the need to keep the Western possessions at all costs, since in the old days "they cut off the right hand of the Huns... If they did not keep garrisons in four inspections The Tufan (Tibetan) troops will not fail to visit the Western Edge, and when the Western Edge is shaken, the awe will extend to the southern Qians. When they start an alliance with them, then Hesi will come into imminent danger... If the north is adjacent to the Tufan, then the ten tribes (Western Turks) and Eastern Turkestan will perish for us."[83]

The performance worked: a new army was equipped, replenished with Western Turks, and in 692 she won a complete victory and liberated the "Western Region" from the Tibetans. At the same time, the Kyans and Mani, obviously disappointed in the Tibetans, returned to Chinese citizenship. Some Tibetans managed to capture, but the survivors, having received land inside China, strengthened the defense of the western border.

The Tibetans' attempt to restore their dominance in the west with the help of the Turkic prince Ashin Suizi was also unsuccessful, and the raid carried out by the Qinling brothers ended in defeat in 695. But Qinling was persistent. In 696 he attacked Liangzhou,[84] and, having won a complete victory, sent an ambassador with peace proposals. Qinling proposed to the imperial government to withdraw the garrisons from the "four inspections" and cede the Nushibi (Tianshan) region to Tibet, so that the Dulu (Semirechye) region would remain behind the empire. The Chinese also demanded the return of the former Togon territory and, given the internal situation of Tibet, deliberately delayed the negotiations.[85] The calculation turned out to be fair; intrigues and a coup d'etat in Tibet once again saved the Tang Empire.”

THE COUP IN TIBET

The protracted war exhausted Tibet and China equally with varying success, but this "fatigue" manifested itself in different ways in both states. Chinese public opinion was generally against the war for foreign possessions, which were needed not by the people, but by the imperial government, which was losing popularity at that time. The Chinese wanted to quietly engage in agriculture, crafts and the study of classical literature, and not go on long hikes on dry steppes and snow-capped mountains.

The imperial government was concerned about the abundance of enemies: the Arabs threatened the Central Asian possessions, the Turks seized the entire north, the Mukri and Kidani in the east were worried. Troops were needed everywhere, and reinforcements had to be sent against Tibet just to hold their positions. Therefore, the imperial government also wanted peace. There was also no unity within Tibet. Although every year booty was brought to the country from the borders,[86] but the lion's share of it went to the Gar family, i.e. relatives, Qinlin's nicknames.[87]

As is usually the case, the sympathies of the opponents of the ruling kind turned to the powerless tsengpo, who occupied the throne at that time. Dudsron turned 25 years old. According to the Dunhuang Chronicle, he had a clear mind and severely punished traitors.[88] He was supported, in addition to the Tibetans themselves, by brave Nepalese mountaineers and militant Western Turkyuts who escaped from the repression of the Tang Empire in Tibet.[89]

Qinling made a mistake by allowing imperial embassies to Tibet. Experienced Chinese diplomats, negotiating peace with the ruler and Tsengpo, stimulated the conspiracy with promises and gifts, which was headed by Tsengpo himself.

The struggle began in 695, when Dudsron executed one of the members of the Gar family. Immediately after the execution, tsengmo (tsengpo's wife) "called a lot of people,"[90] apparently her relatives, to secure the throne from the actions of the army subordinate to the Gar family. In 699, the conspirators, under the pretext of a round-up hunt, gathered soldiers and, capturing more than four thousand supporters of the government, and killed them. Then Dudsron summoned the ruler from the army to the capital, but he, knowing that he was facing certain death, he raised an uprising, hoping for the loyalty of his troops. But the warriors scattered, leaving their commander for their king (tsengpo). Seeing the hopelessness of the situation, Qinling committed suicide, and about 100 of his faithful companions lost their lives with him. Those who chose to stay alive, along with Qinling's son, defected to the Tang Empire. They were received with honor and enlisted in the border troops, since their return to Tibet was excluded.[91]

The situation has changed diametrically. Tibet has lost experienced generals and the best troops. China has acquired eight thousand seasoned warriors. Naturally, the imperial government interrupted peace talks with Tibet, and the war resumed on all fronts.

Now the advantage was definitely on the side of the empire. The Chinese themselves attributed their successes to the inexperience of the new Tibetan commanders. The raids of 700 and 702 were repulsed with heavy losses for the Tibetans.[92] Dudsron's request for peace and marriage with the Chinese princess was supported by tribute in gold and horses, but it did not give results. Chinese diplomats who penetrated into Tibet, despite the border war,[93] informed their government about new difficulties on the way of tsengpo Dudsron: "The dependent states on the southern border — Nepal, India and others — all rebelled." Dudsron died in a campaign against the Hindus in 703 .[94]

The victory remained with the empire, but it was too late. The Tibeto-Chinese war was used by the Turks conquered in 630, among whom discontent matured for 50 years, which led to an explosion of passions and bloodshed.[95]

After the death of tsengpo, tribal uprisings and feuds of nobles broke out again, and Dudsron's brother lost the throne of Nepal.[96] But by 705 The noble families of Ba and Dro restored order, and the Tibetan ambassador, who arrived in China, announced the accession of a new tsengpo — Meagtsom to the throne.[97] Under him, the Buddhists retained their positions; the construction of temples, translations of sacred books and invitations of Indian scientists continued.[98] Buddhism and Bon tried to get used to coexistence.”

THE TIBETO-CHINESE WAR

The Turks who rebelled in 689 tied up most of the forces of the Chinese army, and this made it possible for the Tibetans to return to an active foreign policy. To begin with, they conquered the Dardian principalities of Western Tibet and in 715 broke into Fergana, where no one was waiting for them. They failed to gain a foothold there, but, owning mountainous areas, they posed a constant threat to the Chinese garrisons of the "Western Edge".

On the eastern border, Tibet waged a war with the main forces of China with varying success, which from time to time subsided, but did not stop. On the plain, the regular cavalry of the Tang Empire had the upper hand, but in the mountains — Tibetan troops. This situation lasted until 755, when the rebellion of the commander An Lushan forced the Chinese government not only to withdraw troops from the Tibetan border, but also to accept the help of Tibet to suppress the uprising. The Tibetans took advantage of this and seized the western regions of China, and in 763 they plundered the Chinese capital Chang'an. After that, Tibet turned into a world empire capable of challenging the hegemony in Central Asia from China and the Arab caliphate.

It is not difficult to notice that not Buddhists, but supporters of the Bon cult fought in the ranks of the Tibetan army — horses and bulls or dogs, pigs and sheep were sacrificed at the conclusion of truces and treaties.[99] Aurel Stein discovered near Lobnor, on the left bank of the Khotan Darya, in Miran, Tibetan documents dating back to the VIII or the beginning of the IX century. They are by no means Buddhist, as evidenced by the following facts: a) Tibetan names are mostly not Buddhist in spelling and are not used today; b) some titles go back to the pre-Buddhist sagas; c) the swastika has a Bon form; d) the term "lama" and the prayer "Om mani padme hum" do not occur; in addition, the language and stylistic features of the documents are very different from the language and style of Buddhist literature.[100]

Black Faith regained the positions temporarily lost under Srontsangambo.[101]

So, a highly ambiguous situation was created: the victorious army, relying on broad strata of the people and the ancient religion — bon, found itself in opposition to the throne, because the monarch and a handful of foreign Buddhist intellectuals surrounding him sought peace, because only peace with their neighbors could save them from their own troops. But the aristocrats and Bon priests, having real military power in their hands, could not use it, since their own authority was based on the observance and preservation of traditions, namely, the power of the tsengpo was based on tradition, which thanks to this was, for all its impotence, invulnerable.

Both sides were looking for means to consolidate their position. The mayor tried to marry his heir to a Chinese princess in order to strengthen the throne by a dynastic marriage. The prince, who went to meet the bride, died under unclear circumstances.[102] Then the Mayor himself married a Chinese woman, who bore him a son. The son was immediately stolen and declared the son of a Tibetan, Tsengpo's concubine. They wanted to raise the prince in the Bon faith and finally get rid of Buddhism. But the Buddhists, who managed to explain to the child who his mother was, and inspire him with reverence for her beliefs, did not doze either. Such forms were acquired by the exercise of Buddhism and Bon, monarchical and aristocratic power. The only thing is that the intensity of hatred has not yet reached such an extent that blood flowed to the Tibetan land.

BLACK AND YELLOW

The Tibetan monarch was more powerful and formidable outside the borders of his country than in his own country. The Buddhist yellow faith he patronized could not in any way win the favor of his subjects. The major hospitably welcomed Central Asian Buddhists who fled from the Arab sabres, Chinese and Khotan monks who brought literacy and the preaching of humanity to Tibet, but "although tsengpo extolled the Teachings, Tibetans did not accept ordination as monks."[103] Buddhism was practiced only in the western regions of the country, not inhabited by Tibetans, but in Central Tibet there was not a single monastery, and both the people and the king were equally ignorant of the law of the Buddha.[104]

A decisive role in the brewing conflict was played by a natural disaster — the smallpox epidemic. The Bon priests did not fail to attribute the infection to the charms of foreigners and achieved their expulsion from the country. In 755, tsengpo Meagtsom died,[105] leaving the throne to the minor Tisrondetsan, and the power, until then divided, completely passed into the hands of the aristocracy, in other words, the supporters of the Bon faith. The government was headed by the grandees Mazhani Takralukon, irreconcilable enemies of Buddhism. "The king, although he was a believer himself, could do nothing, because his minister was too powerful,"[106] says the Tibetan chronicle of the Buddhist trend. Majan sent Chinese and Nepalese monks to their homeland, prevented the spread of Buddhist literature and destroyed two temples built in the previous reign.[107] The great Lavran shrine was turned into a slaughterhouse.

Apparently, at this time, the reform of bon was being carried out, which was transformed in the image and likeness of Buddhism. Natives of the near-World countries, called up to replace the Chinese, Khotans and Hindus, compiled a canon of two sections: one had 140, and the other 160 volumes.[108] Through the reform, bon strengthened his position so much that Tisrondetsan himself acknowledged the complete defeat of Buddhism in one of the decrees.[109]

Even Mazhan's political opponents, Tibetan dignitaries who competed with him in the struggle for power and therefore supported the king and Buddhism, proved powerless before the alliance of the aristocracy and the "black church". The monarch helped his supporters only by sending them to the outskirts of Tibet, where Mazhan could not kill them.[110]”

THE MASSACRE

Mazhan made only one mistake: he considered the cause of Buddhism hopeless, whereas there are no hopeless positions in history. His enemies, deprived of power and real power, turned to the tactics of a court conspiracy. They were brave people, and it cost them nothing to kill a person, but... Buddhist teaching categorically prohibits murder. By violating the religious prohibition, the conspirators would compromise their doctrine and thereby condemn their cause to failure. But they found a way out: having lured Mazhan into an underground tomb-cave, they closed the exit from it. At the same time, they believed, no one killed Mazhan, he himself died.

One must think that such sophistry could not convince anyone except the murderers themselves. Therefore, a version was invented for the people that the minister heard a divine voice ordering him to enter the tomb to protect the king from misfortunes, and the door closed itself.[111] Then a legend was composed explaining everything that happened as a chain of laws that arose in previous existences and reincarnations.[112] Obviously, the anti-Buddhist policy was popular among the people, and it was necessary to conceal the crime. Nevertheless, the coup succeeded: Mazhan's friends were sent into exile, to the deserts of Northern Tibet, and Buddhist preachers were returned to the capital.[113]

The king took power into his own hands, and the flourishing of Buddhism in Tibet began again. The idols were reopened, a dispute was arranged on Lhasa Square between supporters of the Bon cult and Buddhism, and the latter, of course, won, but treated the defeated mercifully — only part of the sacred books of the ancient religion were burned, and the other part was accepted by Buddhists.[114]

However, the agreement with the people reached by the new Tibetan king was incomplete. Supporters of the minister buried alive in 754 preferred to go with all their relatives to the side of China, where they were caressed and even received the imperial surname Li, which was the highest honor.[115] There were a lot of defectors, and this could have greatly influenced the course of events if everything had continued to remain the same in China itself. But the crisis in China broke out earlier than in Tibet. It was An Lushan's rebellion.”

LAMAISM AND ITS FOUNDER

The internal policy of Tisrondecan was aimed at strengthening the country. He finally managed to quell the open religious struggle between his subjects. Starting with the treacherous murder of his minister, Tisrondetsan realized that it was impossible to strengthen Buddhism only by violent measures. Therefore, he took care of inviting new teachers from India. Shantarakshita, who was called from India, turned out to be a modest and conscientious person. He refused to compete with sorcerers in conjuring demons, as he considered it the task of a hermit and a teacher to direct his spirit to saving reflections.[116] But another teacher, Padmasambava, who came from the Buddhist University of Nalanda, surpassed the most powerful sorcerers in the art of magic. A new direction of Buddhism, based on the use of magical formulas and magic, was called tantrayana.[117]

Padmasambava's disciples, ode, those in red cloaks abandoned the strict rules of Mahayanic Buddhism: asceticism and morality, but their spells and tricks made a much greater impression on Tibetans than the self-absorption and ecstasy of Mahayanists. Therefore, this time Buddhism had a much greater success. Tibetans enthusiastically looked at the "miracles" shown by a visiting Hindu, and the Bon sorcerers themselves were not averse to adopting magic techniques unknown to them from him, especially since celibacy was not obligatory for Padmasambava's students.[118]

Padmasambava brought a new faith to Tibet not only in form, but also in essence. It was Buddhist in terminology rather than in dogmatics and ethics. The concept of tantrayana developed in Udayan, present-day Kafiristan, a mountainous country west of Kashmir. Udayana has long been famous for its magicians, which was noted by Xuan Zang.[119] Buddhism in it merged with Shaivism [120] and the cult of dakinis, female deities, from whom Padmasambava, according to his fantastic biography, received his magical power.[121] Compromise with the ministers of the cult of Bon allowed to combine both systems, and a new concept. It was called Lamaism; however, this word is used only in European scientific terminology and is unknown in Tibet itself.[122] The Tibetans themselves consider their faith to be real Buddhism — another example of how a familiar word acquires a new content.

Since the reform of Tisrondetsan, Lamaism has become the official ideology of Tibet. To strengthen this doctrine, around 770, the Samye monastery was built not far from Lhasa, which became a school of magic,[123] and Tisrondetsan was declared the embodiment of bodhisattva wisdom — Manzhushri. The monarchy became a theocracy, and the king turned into a guardian deity of the law (darmapala).

The new system met resistance from two sides. Firstly, not all Bon's supporters compromised, and secondly, real Buddhists refused to recognize Padmasambava's teaching as Buddhism. Disputes and discord stimulated the study of the doctrine and translations of Indian writings into Tibetan, and both sides were equally zealous in the latter lesson. Supporters of the "black", i.e. irreconcilable, bon, also joined this fight. Instigated by them, one of the wives of Tisrondetsan, a Tibetan by origin, achieved the exile of a young but learned lama-translator of Vairochana, doing the same as the wife of Pentephria.[124] But after a serious illness befell her, she relented, and the young lama was returned from exile. Nevertheless, this woman in the history of Tibet was declared the incarnation of the "red devil" (the deity of the bon religion).

This essentially three-sided war was the result of a clash of Eastern and Western cultural influences. The inclusion of Dardistan in the Tibetan kingdom opened access to such Hindus as China did not know, who kept the principles of Mahayana rejected in India itself. Tisrondecan himself was the son of a Chinese woman, but he had to make a choice between East and West, which also meant peace or war with China.

THE CATHEDRAL IN LHASA

The bitterness that arose during the long and difficult war between the Tibetans and the Chinese forced the ruler of Tibet to reconsider his attitude to Buddhism. He could not and did not want to refuse to patronize this teaching, but he was even less satisfied with the penetration of Chinese into Tibet, at least in the rags of Buddhist monks. However, it was not easy to get rid of these "holy people", and they themselves tried not to give a reason for exile.

Tisrondetsan found a way out by arranging a public dispute between Buddhist schools: the Chinese defended Mahayana and the principle of "non-doing"; the Indian teacher Kamalashila defended the theory of Sarvastivadins (Hinayanists) and proved the possibility of salvation by "good deeds", i.e. prayers, the construction of idols, alms to monks, preaching, etc. To this, the leader of the Chinese Buddhists, Heshan, objected: "Good and sinful deeds are truly like white and black clouds that equally cover the sky. Liberation from all thoughts, desires and times. Thinking entails a lack of awareness of the reality of individual being… This is the only way to achieve (nirvana).[125]

The decisive circumstance in this dispute was not the arguments of the parties and not the sympathy of the listeners, but the opinion of the monarch, which was biased. Even before the beginning of the dispute, Tisrondetsan expressed himself as follows: "I invited scientists from India to translate the Tripitaka, explain it, establish a community of monks and unite the faith into a single system. Heshan came from China, whose teaching does not correspond to faith. We invited Sage Kamalashila in order not to have two teachers, we will arrange a dispute to unite the teachings of the Buddha. I won't interfere."[126] With this remark, no matter how accurately it was conveyed, the king predetermined the outcome of the dispute, and also revealed the purpose of the dispute — the introduction of unanimity in Tibet. Nevertheless, the debate was far from academic. Several of Heshan's supporters were stoned such that they soon died; for this, the other four Chinese sent by Heshan killed Teacher Kamalashila.[127]

Even promises "not to interfere" the Tibetan monarch did not keep back, because after the dispute, a special decree banned the preaching of all schools of Buddhism, except for the triumphant Sarvastivadin school. The Chinese monks suffered the most, who were not allowed to repent and reconsider their views, but were simply expelled from Tibet. One can think that the whole thing was started just for this. This event is extremely important in its consequences. Now Tibet has become an enemy not just of the Chinese government, but of the entire Chinese culture in any of its manifestations. Hence, the incredible bitterness and tenacity of both sides become clear, because the platform for a possible agreement has disappeared:

Tisrondetsan is considered the successor of the Srontsangambo case, but in fact he is its destroyer. The marriage of the founder of Tibetan Buddhism with a Chinese woman led to an alliance with China and a campaign against India. The half-Chinese Tisrondetsan leaned on the Pamiris and Hindus and took up arms against China. Undoubtedly, religious events in Tibet were closely connected with the turns of its foreign policy. The combination of both was the cause of the brutal seventy years' war, which we can classify as religious wars.

WE WILL ALSO LISTEN TO THE OTHER SIDE

According to Buddhist historiography, the reign of Tisrondetsan was a golden age. The harvests were good, the population increased, the enemies were defeated, the laws both secular and spiritual were strengthened, and the teachings of the Buddha spread, bringing with them a high culture. An attempt was even made to collect chronicles and, by comparing them, create a reliable history.[128] The main role in these reforms is attributed to the Indian sages Shantarakshita, Padmasambava and Kamalashila, and their patron, the king, is declared the incarnation of Manzhushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom and enlightenment.

But the tradition of the rejected Bon religion interprets the epoch in a completely different way. The secondary introduction of Buddhism is attributed to a group of nobles who persuaded the king to become like the kings of India, who, professing Buddhism, are "free from diseases, durable and possess enormous wealth." Here we see the true reason for the union of the throne and the Buddhist community: King Tisrondetsan, like Charles I Stuart, wanted to get rid of the guardianship of his subjects.

However, Buddhism was strengthened only in middle Tibet: upper Tibet remained faithful to the ancient Bon creed, and both religions were professed in lower Tibet. After the above-mentioned dispute, Tisrondetsan legislatively banned the bon religion. The motive of this law is quite clear: "The king gathered the bonpo (sorcerers) and said: "You bonpo are too powerful, and I am afraid that you will make my subjects unfaithful to me. Either convert to Buddhism and become monks, or leave the Tibetan state, or become service people and pay the tax."[129]

The priests accepted the first offer, and many of them became monks, hiding their shrines and manuscripts in mountain caves. The latter circumstance shows how insincere their forced conversion was. The shrines and manuscripts were hidden so that bon could be resurrected when the king, ministers and the Buddhist community will be ruined because they forbid the Bon religion, when the royal family will go to collect alms in the villages and beg for rags from the people, and the bon doctrine will spread to all corners of the world."[130]

One can imagine what a hodgepodge of views began to reign in the Buddhist community and how much the effectiveness of the organization decreased after it absorbed its sworn enemies. At the same time, it should be taken into account that unprincipled people who are not shy about anything have become Buddhists, while the best part of the supporters of the black faith refused to compromise and fled to the mountains. Tisrondecan found himself in a bad environment.

Bon resisted desperately. Natural disasters, such as a flood, the defeat of a prince by lightning, the tsar's illness, etc., were interpreted by the people as punishment for apostasy. The tsar was forced to make an agreement and allocate areas where the confession of the Bon religion was allowed. At the same time, the army still adhered to the black faith, [131] and this forced Tisrondetsan to even greater concessions.

The ruler said: "In order for me to hold on, the Bon religion is needed just like Buddhism; in order to protect my subjects, both are necessary; in order to find bliss, both are necessary. Bon is terrible, Buddhism is venerable; therefore, I will preserve both religions."[132]

So, Bon's vocation was to protect the life of the people (of course, from external enemies), and the task of Buddhism was to achieve bliss (i.e. enlightenment). But they did not come to such a separation of functions immediately. During the life of Tisrondetsan, there were three periods of persecution of bon.

All this brief, dry information gives only a faint idea of the intensity of passions that were tearing Tibet apart at that time. But how this intensity is felt when describing the palace intrigue that preceded the death of Tisrondetsan! His wife, a Tibetan who professed Bon, was the mother of three sons, but the king left her for concubines associated with the Buddhist community. The abandoned queen invited three exiled sorcerers and asked them to bewitch the king. They demanded his dirty undergarments, which could be obtained only by removing them from the body. The queen entrusted this task to her seventeen-year-old son. The tsar was at the palace at that time and was having fun with his entourage. The gatekeeper refused to let the prince in, but he broke down the door and stabbed the gatekeeper. He appeared in front of his father and, hiding nothing, demanded a shirt, which the tsar immediately gave him.

One can imagine what the prince looked like if the king preferred to become a victim of witchcraft than to talk to his own son and heir, who stepped over the corpse of a faithful servant. Tisrondetsan turned to Padmasambava for protection, and he took up the enchantment, but after 14 days Bon witchcraft overcame, as a result of which the exiled priests were returned, and the king died, returning to bon.[133]

According to other sources, Tisrondetsanne died of witchcraft, and renounced the throne in favor of his son.134. Perhaps an incurable disease played a major role in his abdication. This hypothesis reconciles both versions. But one way or another, his policy of religious compromise suffered a complete defeat.

The jealous queen simply poisoned her husband, but her son repented of the patricide and justly accused his mother of it. The fact is that, despite his love for his mother and complicity in the crime, he was a Buddhist.[135] When he became king and took the name Muni Zenbo in 797, he "sent madness upon his mother," which apparently means that he drove her to madness by his conversion. Then the queen poisoned her son, and the power was transferred to his younger brother, Jujie Zenbo.

The short reign of Muni Zenbo was marked by two events that greatly influenced the further course of events. First, he invited lay Buddhists from India and China to his house and ordered them to read the Vinaya Sutra and the Abidarma Tripitaka.[136] These were classical Buddhist treatises, and the followers of Tantrayana had a fair number of rivals from among the Hinayanists and Mahayanists, which could not but cause a split in the camp of Buddhism. The state confession was divided into a number of philosophical schools, which fiercely polemized with each other. Secondly, he forced the rich to share with the starving population three times in a year and a half.[137] This shows that the prosperity of Tibet was very relative: wars and reforms exhausted the people. But more importantly, Muni Zenbo declared himself an enemy of the rich. One can think that he was preparing a social reform,[138] which did not come to fruition due to regicide and a palace coup; very many people were interested in the latter: rich people, nobles, supporters of the Bon religion, Tantrists and the dowager queen who poisoned him.

Perhaps it was the need to hide the intentions of this king from the people that caused some confusion in chronology and inconsistency in the sources. E. Schlagintveit's Muni Zenbo merged with his younger brother Jujie Zenbo into one person, bearing the name Mukri Zenbo. According to the "Blue Notebook", King Tisrondetsan died in 780, but in the "Tang History" indicates 797. Lathasa's entry mentions King Muni Zenbo, whose name is absent in the "Tang History", but is constantly mentioned in the Tibetan chronicles, the "Blue Notebook" reports that King Muni Zenbo ruled from 780 to 797. This seems to be a mistake, since most Tibetan chronicles establish that this king was poisoned by his mother after a short reign (one year and seven months or three years). According to the chronicles, the throne passed into the hands of the heir of Mutug Zenbo, the younger brother of Muni Zenbo. According to Buston, Muni Zenbo was succeeded by his younger brother Creed Zenbo, also called Sadnaleg. Dr. Petoch believes that Juzi Zenbo of the "Blue notebook" is transcribed as Jiuji-jian of the "Tang History", and identifies him with Muni Zenbo, whose years of rule thus fall to 797-804.[139] Yu. N. Roerich considers the question open.

Let's try to approach the problem in a different way: in 797, the Chinese could not know the details of the internal history of Tibet, since the war was in full swing. Therefore, the brief reign of Muni Zenbo not only could, but should have escaped their attention. Then a comparison of the dates of the "Blue Notebook" and the Chinese chronicle shows that the Tibetans lost one and a half or two years from the chronology, i.e. the very time that falls on the reign of Muni Zenbo. Thus, it is possible to find a place for his reign — 797-798,[140] which corresponds to most chronicles, and by shifting the chronology of the "Blue Notebook" by these two years, bring it into agreement with the Chinese chronology, in this case correct.”

THE AGE OF REVENGE

Under Jutze (aka Mutigtsanbo), who reigned until 804, internal contradictions in Tibet did not weaken. The struggle of the court cliques and intrigues, previously restrained by the iron hand of Tisrondecan, began to have a negative impact on the army. One of the Tibetan military leaders, the great-grandson of a Chinese emigrant, bitterly complained to a captured Chinese officer that he would like to, but could not return to the homeland of his ancestors. Another military commander, "fearing that he would not be blamed for unsuccessful actions, submitted to China."[141]

But these were only symptoms of decay, not the decay itself. The next tsar, Sadnaleg (804-816), successfully ended the war, bringing the matter to a truce. He had three sons by his first wife: Jangma, who became a monk, Langdarma, "a friend of sins and an enemy of religion," and a very devout Ralpachan. Since Langdarma quite definitely gravitated towards bon, he was removed from the throne, to which in 817 Ralpachan joined in.[142]

The era of Buddhism's attack on Bon and even Tantrism has come, as the king was surrounded by Indian Hinayanist monks. "It was an era of accumulating merit."[143] The fact is that the Hinayanists recommended the "slow way of salvation" through the accomplishment of "good deeds", while the Mahayanists preferred the "fast way", i.e. asceticism and "non-doing". Mahayana was more profitable for the people, since it is easy to feed a hermit sitting in a cave, but the payment for good deeds, i.e. the construction and decoration of idols, translations and correspondence of prayers, etc., fell on the shoulders of the draft class. Many monasteries were built under Ralpachan, and Buddhism turned into an expensive religion. Lamasery acquired the character of an organization divided into three degrees: novices, contemplatives and "perfect", and the latter were ranked among the highest estate.

Each "perfect" received seven serfs for maintenance and services. The Lamaist organization was released from its duties, and it was granted its own court. Grateful lamas declared Ralpachan to be the incarnation of Vajrapani, the master of lightning, incorporated by Buddhism of the ancient god Indra.[144]

The people who built monasteries and fed many foreign lamas treated the tsar's policy quite differently. The economy of the country fell into decline, general impoverishment began, and murmurs arose. "Who benefits from our impoverishment and oppression?" — people asked. And pointing contemptuously at the lamas, they said: "Here they are." The tsar issued a decree: "It is strictly forbidden to look contemptuously at my clergy and point fingers at them, whoever allows himself to do this in the future will have his eyes gouged out and his index finger cut off."[145]

But not only that: the Hinayanist Buddhists quite consistently from their point of view decided to do "good deeds" in the political life of Tibet. Already under Tisrondetsan, Buddhist monks Yonten from the Trank clan and Tinjin from the Nyang clan were appointed as advisers, "authorized to draw up a great decree", which was lower in rank than the "minor lords", but higher than the "great advisers".[146]

Under Ralpachan, the Buddhists formed their own government; at its head stood Yonten, who received the title of "Commissioner for drafting the great decree, head of external and internal affairs, governor of the state, great monk, Most Illustrious Yonten."[147] This government performed "good deeds" incredibly cool: "Thieves, robbers, deceivers, schemers were exterminated, and those subjects who were hostile to the Teaching or dissatisfied with it were severely punished, their property was confiscated, and they found themselves in deep poverty."[148]

Not only the masses of the people suffered from these "good deeds", but also the aristocrats, who were ousted from power and became the victim of any informer who could almost sincerely accuse a Tibetan nobleman of loving his wife more than the Buddha. But denunciation is a double—edged phenomenon: the "great monk" Yonten experienced it for himself. He was slandered and executed, and after that the conspirators strangled Ralpachan himself and enthroned Prince Langdarma, a supporter of the black faith, to the throne in 839. The Buddhist offensive against Tibet has collapsed.

It is all the more important that Bon, having obtained an edict of tolerance from Tisrondetsan, retained his position under Ralpachan. At the ceremony of concluding a peace treaty in 822, the rite of the black faith even preceded the Buddhist one.[149] The new tsar had on his side an organized party, whose will he willingly carried out.

LANGDARMA

The first act of the new king was the confiscation of the property of monasteries, as a result of which many Hindu Buddhist scholars immediately left Tibet, but Tibetan Buddhists had nowhere to go, and persecution fell upon them, not inferior in ferocity to the tragedies of Louis XIV. By the decree of the king, in violation of the Buddhist doctrine prohibiting killing, half of the monks were obliged to become butchers, and the other half — hunters; those who refused were beheaded. Buddhist books and art objects were destroyed. It was forbidden to pray; worldly goods were declared the meaning of life. But even a Buddhist source notes that "people did not regret that the laws were violated."[150]

The Buddhists developed a frenzied anti-government propaganda: Langdarma was accused of drunkenness,[151] and even for the original hairstyle (the king did not braid a braid, as was customary at that time, but collected hair on the crown, and a rumor was spread that he was hiding horns that grow on his head and prove his demonic nature),[152] called him the rebirth of a rabid elephant tamed by the Buddha.

These conversations did not bother the tsar, who believed that people who turned away from murder were safe for him. However, one lama decided to sacrifice his soul for the sake of common salvation. He dressed in a cloak, black on the outside and white on the inside, and, hiding a bow and arrow under the cloak, appeared at the reception to the king. The black clothes allowed him to pass by the guards, who mistook him for a priest. At the first bow he put an arrow on the bow, at the second — pulled the string, at the third — shot at the king.[153] The confusion that arose allowed him to run for the nearest shelter, where he turned his clothes inside out and thanks to this he escaped from persecution and fled to Kam, where Buddhists found shelter and protection.[154] It was in 842[155]”

THE COLLAPSE OF THE TIBETAN MONARCHY

Langdarma's short reign was marked by the last success of Tibetan foreign policy: in 839, i.e., in the year of the accession of Bon's protege to the throne, the Kyrgyz, who were at war with the Uighurs, went on the offensive and dealt a fatal blow to the Uighurs. It is difficult to assume that these events did not have an internal connection. In the Kyrgyz inscription from Altyn-Kel it is reported that "the hero Eren Ulug ... for the sake of valor (i.e. on military matters) went to the Tibetan Khan as an ambassador and returned."156. The Uighur people were on the verge of death, and if the death of the Tibetan king had been delayed, the Uighurs would have disappeared from the face of the earth, like the Turks, a hundred years earlier. But the Tibetans could not take advantage of the long-awaited success, as internal hostility turned into an open war.

This is the most "dark period" in the history of Tibet, and Tibetan sources, touching on it, sharply differ from Chinese ones. According to the Tibetan chronicle, Odsrun, the son of Langdarma, returned to Buddhism, as did his heir Delalkhrontsan, under whom the uprising and the complete disintegration of the state began.[157] According to Chinese history, Langdarma's three-year-old nephew was elevated to the throne and the queen mother became regent, which caused an immediate civil war.[158]

However, when analyzing the events, it is clear that the Tibetan version complements and clarifies the Chinese one: after the murder of Langdarma, the government capitulated to the Buddhist community. This follows from the fact that the opponents of the queen mother were the ruler of the Gaduno affairs and the commander Shan Kunjo, the closest employees of the Langdarma, and their opponent Shan Bibi, known for his bookish scholarship, was appointed military governor by Ralpachan himself.[159] Not only that, Gaduno, objecting to the new king, said: "After the late gambo (tsengpo), many youths remained, and the son of the Linskis (i.e., from the family of the queen) was elevated to the throne. Which of the nobles will obey him? Which of the spirits will smell his sacrifices? The kingdom will inevitably perish."[160]

The reference to the nobles shows the social background of the protest, and the appeal to the spirits shows its ideological orientation. The uprising was raised by supporters of the aristocracy and the black faith. Gaduno was executed, but Shankunjo took up arms, declaring himself the avenger of Langdarma. In 843 "the first ranks in the state rebelled because of the unfair construction of gumbo" (tsengpo).[161] The "first ranks" were the proteges of the Langdarma. The opponent of the rebels, Shang Bibi, lulled the vigilance of Shang Kunjo with negotiations, inflicted an unexpected sensitive defeat on him, and the civil war flared up.

The second attempt of the offensive of the army (consisting, as already mentioned, of supporters of the Bon faith) against the well-organized army of Shan Bibi, undertaken in 845, also ended in failure. Only by 849 Shang Bibi was pushed out of the borders of Tibet proper, to the northern side of Nanshan.

Shankunjo, pursuing the enemy, devastated the whole country from the Chinese border to the Karashara. He tried to negotiate with China and get them to agree to recognize himself as the Tibetan king, but the emperor refused him, after which Shankunjo tried to gather troops for a war with China. The supply of the army was so poorly organized that it forced the Tibetan warriors to flee from the devastated country, and the Shankunjo army melted away. The Chinese used this in order to occupy part of the territory taken from them by the Tibetans in previous wars, and in 851 The Tibetan governor of the Hexi region (north of Nanshan) was transferred to China. In Dunhuang since 847 The Uighurs were established, with whom the supporters of Shanbibi made an alliance.[162]

Shankunzho tried to restore the power of Tibet in the fallen areas, but in 861 he was defeated first by the rebels, and then by the Uighur prince Bugu Jun and in the last battle lost his head, which was sent to Chang'an.[163] The Tibetan kingdom ceased to exist. The heir of the last Tibetan king fled from the usurper with only a hundred horsemen. The whole of Tibet was engulfed by the uprising of "people dressed in cotton clothes,"[164] i.e. the poor. Suffering hunger and deprivation, the prince made his way to the Ngari region, where in about 850-853 he found shelter and safety for himself and his Buddhist supporters.165. In the rest of Tibet, the cause of Buddhism was lost.

But Bon didn't win either. The expulsion of the Buddhists, i.e. the most cultured force within Tibet, had such a negative impact on the state of the administration, the organization of the national economy and even the discipline of the army that the throne fell. And without the support of the authorities, the bon organization could not exist; it turned into a sect, i.e. it did not bind, but divided the country.

Tibet has disintegrated into its component parts. Every castle, every monastery, Bon or Buddhist, was fenced off with walls, every tribe put out patrols on their pastures to kill strangers. The remnants of Tibetan culture, which took more than 200 years to revive, were drowned in the streams of blood shed hourly.”

NOTES AND REFERRENCES.

1 Kozlov P. K. Tibet and the Dalai Lama, II, Pg., 1929, pp. 8-10; Roerich Yu. N. Nomadic tribes of Tibet//Countries and peoples of the East. Issue II, M., 1961, pp. 8-9.

2 Francke A. History of Western Tibet, L., 1907, p. 19-39.

3 Gumilev L. N. Efthalites and their neighbors in the IV century. //VDI, 1959, No. 1, p. 135.

4 Grumm-Grzhimailo G. E. Materials on ethnology Amdo and the regions of Kukunor, St. Petersburg, 1903, p. 3.

5 Terrien de Lacouperie, Les langues de la Chine avant les chinois //Le Museon, 1888 p. 28-29.

6 Ibid, p. 335.

7 Grumm-Grzhimailo G. E., pp. 41 and 43.

8 Chavannes E. Les pays d'Occident d'apres Wei-lio //T'oung Pao. Ser. II, 1905, vol. VI.

9 Uspensky V. The country of Kuke-nor or Qing-hai //IIRGO notes on the Department of Ethnography. 1880, vol. IV, St. Petersburg. (otd. ott., p. 51).

10 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin). The History of Tibet and Khukhunor, vol. I, St. Petersburg, 1833, pp. 110-111.

11 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), pp. 124.

12 Kozlov P. K. Mongolia and Kam, M., 1947, pp. 215.

13 Gumilev L. N. Hunnu, M., 1960, pp. 205-207, 225-231.

14 Bogoslovsky V. A. An essay on the history of the Tibetan people, M., 1962, p. 24.

15 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 127

16 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 26

17 V. A. Bogoslovsky believes that this is only a male population, warriors ("Essay of history ...", p. 128). But then the total number would be about 15 million, which is impossible, given the natural conditions of Tibet.

18 The literature of the question is very extensive. Here are just some of the most important works: Francke A. A History of Western Tibet; Bell Ch. The Religion of Tibet, Oxford, 1931; Laufer B. Uber ein tibetisches Geschichtswerk der Bonpo //T'oung Pao. Ser. II, 1901, vol. II; Hoffmann H. Quellen zur Geschichte der Tibetischen Bon-Religion, Wiesbaden, 1950; Tucci G. The Tombs of Tibetan Kings, Rome, 1950; Labou M. Les religions du Tibet, P., 1957.

19 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 29

20 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 31.

21 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 127; Grumm-Grzhimailo G. E. Western Mongolia and the Uriankhai Region. Vol. II, L., 1926, pp. 184-185.

22 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), pp. 125-126 and 234.

23 Bogoslovsky V. A., pp. 140-143.

24 Iakinf (N. Ya. Ya. Bichurin), pp. 127-128.

25 Gumilev L. N. Legend and reality in the ancient history of Tibet //Bulletin of the History of World Culture, 1960, No. 3, p. 107.

26 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 94.

27 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 97 and 172.

28 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 128-130.

29 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 131.

30 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 172.

31 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 79-80.

32 This practice persisted in Tibet until the twentieth century . It was observed by Rockhill and Grenard in Northeast Tibet and likened to feudal (Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 84)

33 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 101-104

34 See: Engels F. The origin of the family, private property and the state // Marx K., Engels F. Essays, ed. 2. Vol. XXI, p. 129.

35 "... the workers were conquered" (Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 35). See: Gumilev L. N. Biography of the Turkic Khan in the "History" of Theophylact Simokatta and in reality // Byzantine Time, 1965, XXVI, p. 76.

36 Let's remember "Odyssey": the people defend the king, insulted by the nobility.

37 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 36.

38 According to the Tibetan version of the royal family tree, Srontsangambo was the thirtieth tsenpo to inherit his position. Consequently, during the period from 420 to 580, that is, over 160 years, 29 rulers were replaced and for each, on average, 5.5 years. This could only be the case when the throne was in the hands of the frond nobility, who changed their henchmen at will. The Chinese version (Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 130) considers him the sixth tsengpo, probably due to less awareness. The chronology in both cases is missing until the VII century . Even the date of birth and accession to the throne of Srontsangambo cannot be established. See: Kuznetsov B. I. The Tibetan Chronicle "The Bright Mirror of Royal pedigrees", L., 1961, pp. 73-74.

39 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 36.

40 The spelling of Tibetan names has not yet been established by Tibetologists. Different translators spell the same name differently. Sometimes the basis is transliteration, sometimes transcription, sometimes phonetic notation from a particular dialect, and sometimes even Chinese transliteration. So, the name we mentioned is written by E. Schlagintweit (Schlagintweit E. Die Konige von Tibet, Munchen, 1886) Srong-btsan sgam-po; in A. Franke (Francke A. A History of Western Tibet) — Shrong tsan sgampo; at Demieville (Demieville P. Le Concile de Lhasa, Paris, 1957) — Sron-bcan-sgam-po; at B. I. Kuznetsov (The Tibetan Chronicle "The Bright Mirror of Royal Pedigrees") — Srontsangambo; V. A. Bogoslovsky ("Essay on History ...") — Songtsen-gam-po and, finally, Bichurin, who translated from Chinese (The History of Tibet and Huhunor), — Qizong Longjian. Not all pronunciation and spelling variants are given here, and the difficulty of quoting numerous authors increases in the absence of a single spelling principle due to the need to quote accurately. Therefore, one or another system of name reproduction will not be sustained in our narrative. In the most critical cases, the footnotes will contain discrepancies that are important for understanding the text and verifying it with the source-translation.

41 Shcherbatskoy F. I. Buddhist philosopher on monotheism //Notes of the Eastern Department of IRAQ. 1906, vol. XVI.

42 Bongard-Levin G. M. Agrams — Ugrasena — Nanda and the accession of Chandragupta //VDI, 1962, No. 4, p. 15.

43 "After the victory, he (Chandragupta) turned the slogan of freedom into slavery, because, having seized power, he himself began to oppress the people whom he freed from foreign domination" (Justin XV, 4, 13-44) (Bongard-Levin G. M. Agrams —Ugrasena—Nanda and the accession of Chandragupta //VDI, 1962, No. 4, p. 19).

44 Getty A. The Gods of Nonhern Buddhism, Oxford, 1914, p. 163.

45 Legge J. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms being an account by the Chinese Monc Fahien, Oxford, 1886.

46 Julien St. Histoire de la vie de Hiouentsang et des voyages dans l'Inde... //Memoires sur les contrees occidentales traduits de sanscrit en chinois en l'an 648 par Hiouentsang. T. I–II, Paris, 1857– 1858.

47 Grigoriev V. V. Eastern or Chinese Turkestan. Vol. II, St. Petersburg., 1873, p. 153.

48 Chavannes E. Les religieux eminents par I-tsing, Paris, 1894, p. XV.

49 Ibid, p. XVII.

50 Bell Ch. The Religion of Tibet, p. 10.

51 Ibid, p. 19

52 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 132.

53 The alliances of Tibet with Nepal and China were sealed by marriages with a Nepalese princess in 639 and a Chinese princess in 641.

54 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 41, 48, 89.

55 Cordier H. Histoire generate de la Chine, I, p. 416.

56 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 41.

57 This is how he can be called after the reforms he carried out, although the process of formation of the monarchy in Tibet was delayed and not completed.

58 This was the second attempt at Buddhist preaching in Tibet. The first, under Latotori, was not successful, and the Indian missionaries returned home. See: Roerich O. N. The Blue Annals, Calcutta, 1949, p. 38.

59 Popov I. Lamaism in Tibet, its history, teachings and institutions, Kazan. 1898, p. 143.

60 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 40.

61 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 135.

62 Bell Ch. The Religion of Tibet, p. 34.

63 Roerich G. N. The Blue Annals, p. 40.

64 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 135.

65 aka — Tong-tseng (according to V. A. Bogoslovsky), kit. Ludong-tsan (by I. Bichurin).

66 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 136.

67 Kuznetsov B. I. The Tibetan Chronicle "The Bright Mirror of royal pedigrees", p. 50 Bell Ch. The Religion of Tibet, p. 10.

68 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 93.

69 A certain nobleman wanted to capture the khan and his wife, a Chinese princess, and take them to Tibet (Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 94).

70 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 95, 135.

71 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 95, 136.

72 Tibetan reading is not established. Possible options: "Tri-dring", "Con-Ling", "ThimLing". See: Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 49.

73 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin). Collection of information about the peoples who lived in Central Asia in ancient times. Vol. II, M.-L., 1950, p. 120 and sl.

74 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 136-137.

75 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 138; Chavannes E. Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux, St. Petersburg, 1903 ("Collection of works of the Orkhon expedition", vol. VI), p. 281.

76 Bukhain-Gol is a small river flowing into Lake Huhu—Nor from the west, it crosses a wide valley and is surrounded by a rare coastal forest. See: Kozlov P. K. Mongolia and Amdo, M.-L., 1923, pp. 312-313: Kuner N. V. Description of Tibet. Part I, issue 2, p. 30.

77 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 142.

78 Grumm-Grzhimailo G. E., p. 292

79 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 143; Du-song (according to V. A. Bogoslovsky, p. 50); Gun-Sron-do-rzhe (Schlagintweit E. Die Konige von Tibet, p. 50), kit. Qinu-Sinun (Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 143).

80 Dansyans, i.e. Tanguts, who inhabited the right bank of the Yellow River south of Lake Huhu-Nor. See: Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 237.

81 Man — the common name of the southern forest tribes. See: Grumm-Grzhimailo G. E., p. 27

82 Army sent against the Tibetans in 690, it was returned from the road. See: Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 146.

83 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 147-149.

84 Liangzhou-fu in Alashan

85 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 153.

86 Schlagintweit E. Die. Konige von Tibet, pp. 50-51.

87 This is clearly indicated by a quote from the Dunhuang Chronicle: "In the small Chapu Valley, a subject aspires to become a ruler, the son of Gar aspires to become a ruler." See: Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 52.

88 See: Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 52

89 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 50

90 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 51.

91 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 154.

92 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 155.

93 In 703, the Chinese ambassador Kam Kang even honored tsengpo. See: Bogoslovsky V. A., pp. 52-53.

94 This date should be preferred. See: Kuznetsov B. I., p. 75, and Sinha N. K., Banerjee A. C. History of India, M., 1954, p. 100; cf.: Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 53.

95 For more details about this, see: Gumilev L. N. Ancient Turks, ch. XXI, M., 1967.

96 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 54.

97 When he ascended the throne, he was 7 years old. This means that the power was again in the hands of noble families who put a child on the throne to rule the country on his behalf. His full name is Tridetsukten Meagtsom

98 Kuznetsov B. I., p. 25

99 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 189.

100 Bell Ch., p. 44.

101 For a detailed description of the wars of Tibet in Central Asia, see: Gumilev L. N. Ancient Turks.

102 Kuznetsov B. I., p. 25.

103 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 58.

104 Demieville P. Le Concile de Lhasa, Paris, 1957, p. 18.

105 See: Kuznetsov B. I., p. 82. Yu. N. Roerich proposed the date — 745 See: Roerich G. N., p. XIX.

106 Bell Ch., p. 35; Roerich G. N., p. 40–41.

107 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 59.

108 Roerich G. N. Trails to Inmost Asia..., New Haven, 1931, p. 357

109 Tucci G. The Tombs of Tibetan Kings, p. 98

110 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 60.

111 Roerich G. N., p. 42.

112 Gumilev L. N. Legend and reality in the ancient history of Tibet //Bulletin of the History of World Culture, 1960, No. 3, pp. 103-114.

113 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 61.

114 Popov I., p. 154.

115 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), I, p. 175.

116 I. Popov calls him Kanbo-bodhisattva (Lamaism in Tibet, p. 155)

117 Grousset R. Histoire de l'Extreme-Orient, I, P., 1929.

118 Ibid, p. 361.

119 Waddel L. A. The Buddhism of Tibet or Lamaism, L, 1895, p. 26.

120 Popov I., pp. 157.

121 Grunwedel A. Mythologie du Buddhisme, Leipzig, 1900, p. 52

122 Waddel L. A., p. 28.

123 Grunwedel A., p. 56-57.

124 Waddel L. A., p. 29

125 V. A. Bogoslovsky (pp. 65-66) suggests that the Indian point of view won because it was clearer to the people and suited the ruling class. It seems that both concepts were equally exotic and alien to Tibetans, but the decisive role was played by the blood shed in the battles with the Chinese, and the hopes of receiving material assistance from Indian possessions, for which a compromise with Indian scientists was necessary.

126 Kuznetsov B. I., p. 43-44.

127 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 66.

128 Schlagintweit E., p. 55.

129 Laufer B., p. 22-44, 38-39.

130 Ibid, p. 40.

131 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), I, pp. 189-191.

132 Laufer B., p. 42-44.

133 Ibid.

134 Schlagintweit E., p. 56

135 Tucci G., p. 73.

136 Schlagintweit E., p. 56; Popov I., p. 158.

137 Schlagintweit E., p. 56; Popov I., p. 158.

138 Gold, silver, pearls, turquoise and clothing were seized from the population. Monasteries were not subject to taxation. The population did not believe in the redistribution of property, believing that it would remain in the treasury and would not fall into the hands of the poor. Even the Buddhist priests themselves were against the equation of property, explaining to the tsar that poverty comes from sins in a past life and therefore cannot be eliminated (see: Kuznetsov B. I., pp. 45-46).

139 Roerich G. N., p. XX

140 B. I. Kuznetsov came to a similar conclusion, although in a different way (p. 78).

141 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), I, pp. 208-209.

142 According to B. I. Kuznetsov (Tibetan Chronicle) — Tidesrontsan, according to G. Tucci (The Tombs of Tibetan Kings) — Denti.

143 Schlagintweit E., p. 58

144 Griinwedel A., p. 181.

145 Schmidt 1.1. Geschichte der Ost-Mongolen und ihres Furstenhouses, St.-Pbg., 1829, p. 345.

146 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 71

147 Bogoslovsky V. A., p. 71.

148 Schmidt I. J. Geschichte der Ost-Mongolen

149 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), I, pp. 220-221.

150 Schlagintweit E., p. 60.

151 Roerich G. N., p. 53.

152 Francke A. A History of Western Tibet, p. 56-60; cf.: Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), I, p. 232.

153 Kuznetsov B. I., p. 56

154 Kuznetsov B. I., p. 57.

155 On Chinese chronology

156 Malov S. E. Yenisei writing of the Turks, M. — L., 1952, pp. 56-58. Even if we assume that this embassy was before, the inscription shows the nature of Tibetan-Kyrgyz relations.

157 Schlagintweit E., p. 62.

158 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), I, p. 226 and sl.

159 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 228

160 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 227.

161 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin)

162 The fate of Shang Bibi himself is unknown; after 849, his assistant Tobahuai-guan commanded the army.

163 Iakinf (N. Ya. Bichurin), p. 233.

164 Schlagintweit E., p. 62.

165 Two idols were built in the Ngari region — in the year of the horse and in the year of the sheep (ibid, p. 63), which corresponds to 850 and 851, or 862 and 863. In the 50s, the usurper Kunjo was at the head of Tibet, so early dating should be preferred.