Notes of the cavalryman. Memoirs of the First World War

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev, Lev Gumilev's father was in the Tzar's military

The most outstanding representative of the Silver Age poetry, Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev went to the front as a volunteer in 1914, despite the fact that in 1907 he was exempted from military service. The book "Notes of a Cavalryman" - a documentary story about the first years he spent in the ranks of the 1st Squadron of the Life Guards Lancer Regiment. Before us - vivid pictures of war, presented through the eyes not so much as the poet-acmeist, but as the cavalryman, who courageously shared the hardships of military life with the privates. It was a war of infantry, Artillery and scouts, maybe something like the present conflict. Many people were killed in WWI, not reported here. Then the Bolsheviks arranged a peace and left the war.

In 1921, Nikolai Gumilyov (the father) was accused of counter-revolutionary conspiracy by the Bolsheviks and shot. His son was 9 years old.

Contents

N.S. Gumilev p 5

Chapter 1 p 6

Chapter 2 p 8

Chapter 3 p 12

Chapter 4 p 15

Chapter 5 p 19

Chapter 6 p 24

The end of the introductory excerpt. 26

Chapter 1

As a free-rider-hunter in one of the cavalry regiments, the work of our cavalry appears to me as a series of separate, quite finished tasks, followed by a rest filled with the most fantastic dreams of the future. Whereas the infantrymen are the day laborers in the war, carrying the burden of the war on their shoulders, the cavalrymen are a merry band of travelers, singing and singing to the end of a long and arduous task in a few days. There is no envy, no competition. "You are our fathers," says the cavalryman to the infantryman, "you are like the stone wall behind you”.

I remember it was a fresh, sunny day when we were approaching the border of East Prussia. I was part of a detachment sent to find General M., whose detachment we were to join. He was on the battle line, but where that line stretched, we did not know exactly. Just as easily as on our own, we could have ridden out on the German territory. Already very close, like great sledgehammers, the German guns were thundering, and ours were roaring back at them with volleys. Somewhere convincingly fast in its childish and strange language the machine gun babbled incomprehensible. The non-private airplane, like a hawk above a quail hiding in the grass, stood over our line-up and began to descend slowly to the south. I saw its black cross through the binoculars. That day will forever remain sacred in my memory. I was a patrolman, and for the first time in the war I felt the tension of the will, right up to the physical sensation of some kind of petrification, when one must ride alone into the woods, where a hostile chain might be lodged, and gallop across a field, plowed and therefore impossible to retreat quickly, toward a moving column to see if it would fire on you. And on the evening of that day, a clear gentle evening, I heard for the first time behind a rare lane the growing roar of "hurrah" with which V. The fiery bird of victory that day lightly touched me too with its huge wing. The next day we entered the ruined city, from which the Germans were slowly retreating, pursued by our artillery fire.

Squelching in the black sticky mud, we approached the river, the border between the states, where the guns stood. It turned out that there was no point in pursuing the enemy in horseback: he was retreating unperturbed, stopping behind every cover and ready to turn every minute - quite a savage, accustomed to dangerous fights, like a wolf. It was only necessary to grope him to give directions as to where he was. There was enough separation for that. Over a shaky, hastily made pontoon bridge our platoon crossed the river.

We were in Germany. I have often thought since then about the profound difference between the conquering and defensive periods of war. Of course, both are necessary, only to crush the enemy and to win the right to a lasting peace, but the mood of the individual soldier is not only affected by general considerations - every trifle, the occasional glass of milk, the slanting sunlight illuminating a group of trees, and your own lucky shot are sometimes happier than the news of a battle won on another front.

These highways, running in all directions, these groves cleared like parks, these stone houses with red tiled roofs, filled my soul with a sweet thirst for advancement, and the dreams of Ermak and Perovsky and other representatives of Russia, conquering and triumphant, they seemed so close to me. Is this not the road to Berlin, the opulent city of soldierly culture, which must be entered not with a student's staff in hand, but on horseback and with a rifle behind his shoulders? We went lava, and I was a sentinel again. I rode past the enemy's abandoned trenches with broken rifles, tattered bandages, and piles of ammunition. Red stains were visible here and there, but they did not cause the embarrassment that comes with the sight of blood in peacetime.

There was a farm on a low hill in front of me. The enemy could be hiding there, and I took my rifle off my shoulder and cautiously approached it. An old man, long past the age of the Landsturmist, looked at me timidly out of the window. I asked him where the soldiers were. Quickly, as if repeating a lesson, he answered that they had passed half an hour ago, and showed me the direction. He was red-eyed, with an unshaven chin and gaunt hands. He must have been the kind of man who shot our soldiers with a Montecristo during our campaign in East Prussia. I did not believe him and drove on. Five hundred paces beyond the farm started the forest, which I had to drive into, but my attention was caught by a pile of straw, in which I guessed by my hunter's instinct something interesting to me. The Germans might be hiding in it. If they came out before I noticed them, they would shoot me. If I saw them come out, I would shoot them. I started circling the straw, listening carefully and keeping my rifle weighted down. The horse snorted, wagged its ears, and obeyed reluctantly. I was so absorbed in my exploration that I didn't immediately notice the occasional crackling sound from the woods. A light cloud of white dust, rising five paces away, caught my attention. But it was only when the whine of a bullet flew over my head that I realized that I was being shot at, and from the woods. I turned around to see what I should do. He was galloping back. I had to go too. My horse galloped at once, and as my last impression I remembered a big figure in a black overcoat and a helmet on his head, coming out of the straw on all fours with a bear-like grip. The gunfire had already subsided when I joined the dismount. The cornet was pleased. He had discovered the enemy without losing a single man in the process. In ten minutes, our artillery would take up the cause. And I was only painfully offended that some men had fired at me, challenged me with it, and I did not accept it and turned away. Even the joy of being out of danger did nothing to soften this sudden boiling thirst for battle and revenge. Now I understood why cavalrymen were so eager to attack. To come upon men who, hidden in bushes and trenches, are safely shooting at prominent horsemen from afar, to make them pale from the ever-increasing clatter of hooves, from the flashing of naked sabers and the menacing sight of bent pikes, to overturn, like a blow, three times as strong an enemy, is the only justification for a cavalryman's whole life.

On the next day I also experienced shrapnel fire. Our squadron was occupying W., which the Germans were fiercely bombarding. We stood in case of their attack, which never happened. Only until evening, all the time long and not without pleasantness, shrapnel was singing, plaster was falling off the walls, and in some places, houses were on fire. We went into empty apartments and boiled tea. Someone even found a terrified resident in the basement who was more than willing to sell us a recently slaughtered piglet. The house where we ate it was pierced by a shell shortly after we left.

Chapter 2

The hardest thing for a cavalryman in war is waiting. He knows that it costs him nothing to flank the moving enemy, even to be in his rear, and that no one will surround him, cut off the escape route, that there will always be a saving path, along which an entire cavalry division will easily gallop away from under the very nose of the deceived enemy. Every morning, after dark, we would get out to our position and spend the whole day behind some hillock, either covering artillery or just keeping in touch with the enemy, tangled among ditches and hedges. It was deep autumn, the sky was blue and cold, the branches were sharply black with golden scraps of brocade, but there was a piercing wind from the sea, and we were dancing around the horses with blue faces and flushed eyelids, and sticking our stiff fingers under the saddles. Strangely, the time did not last as long as one might have expected. Sometimes we went platoon to platoon to get warm and floundered on the ground in silent heaps. At times we were amused by shrapnel bursting nearby, some were timid, others laughed at it and argued about whether the Germans were shooting at us or not. It was only when the lodgers left for their bivouac that we were really longing for twilight to follow them. Oh, low, stuffy hovels, with chickens clucking under the bed and a ram settled under the table; oh, tea! which you can only drink with sugar in a bite, but not less than six glasses; oh, fresh straw! spread all over the floor for sleeping; no comfort is ever dreamt of with such greed as you!!! And maddeningly daring dreams that when asked about milk and eggs, instead of the traditional answer, "Vschistko germany taken," the hostess would put a jar of thick cream on the table, and that a big scrambled egg and lard would sizzle happily on the stove! And the bitter disappointment of having to spend the night in haylofts or on sheaves of unmilled grain, with tenacious, prickly spikes, shivering with cold, jumping up and dismounting from the bivouac on alarm!

A detachment of Russian soldiers on their way to the front

We once undertook a reconnaissance offensive, crossed to the other bank of the Sh. River and moved across the plain to a distant forest. Our aim was to make the artillery speak.(8)

The cavalry was in the air, and it really began to speak. A deafening shot, a long howl, and about a hundred paces from us a white cloud of shrapnel burst. The second burst fifty paces away, the third at twenty. It was clear that some Ober-Lieutenant, sitting on a roof or in a tree to correct the firing, was bellowing into a telephone receiver: "Right, right!" We turned and galloped away. A new shell exploded right above us, wounded two horses and shot my neighbor in the overcoat. We could no longer see where the next rounds came from. We galloped along the paths of a well-groomed grove along the river under cover of its steep bank. The Germans had not thought to shell the ford and we were safe without casualties. Even the wounded horses did not have to be shot; they were sent to be cured. The next day the enemy withdrew somewhat and we found ourselves on the other bank again, this time as a lookout. The three-story brick structure, a ridiculous mix of a medieval castle and a modern apartment building, was nearly destroyed by shells. We took shelter in the lower floor on crumpled armchairs and couches. At first, we kept our heads down so as not to betray our presence. We looked quietly at the German books we found there, and wrote letters home on postcards with a picture of Wilhelm on them.

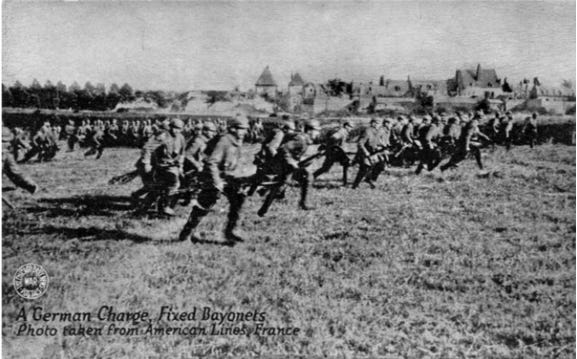

German soldiers

A few days later on a fine, not even cold, morning the long-awaited thing happened. The squadron commander assembled the non-commissioned officers and read the order for our offensive across the entire front. To advance is always a joy, but to advance on enemy ground is a joy heightened by pride, curiosity, and some immutable sense of victory. The men are getting fitter in their saddles. Horses pick up their pace.

A time to be breathless with happiness, a time of sparkling eyes and unaccountable smiles. On the right in three’s, we gallop down Germany's white, tree-lined roads in a long serpentine formation. The inhabitants were removing their hats, the women were hurriedly bringing out their milk. But they were few in number, most of them fleeing for fear of retribution for their betrayed outposts and poisoned spies.

I especially remember an important old gentleman sitting in front of an open window of a large manor house. He was smoking a cigar, but his eyebrows were furrowed, his fingers nervously rubbed his gray mustache, and in his eyes was read mournful amazement. Soldiers passing by glanced at him timidly and exchanged whispers: "A serious gentleman, probably a general... "Well, he must be mean when he's swearing..."

Here behind a wood was heard shotgun fire - a party of the backward German scouts. A squadron rushed there and everything was silent. Here a few shrapnels exploded over us one after another. We scattered, but kept moving forward. The fire had stopped. We could see that the Germans were retreating with determination and irrevocability. No signal fires could be seen anywhere, and the wings of the mills were hanging in the position of the wind, not where German headquarters had given them. We were therefore greatly surprised when we heard frequent gunfire in the distance, as if two large squads were fighting each other. We went up the hill and saw an amusing sight. There was a burning wagon on the tracks of the narrow-gauge railroad, and it was making these noises. It turned out to be filled with rifle ammunition, the Germans in their retreat had abandoned it and ours had set it on fire. We laughed when we found out what it was all about, but the retreating enemy must have spent a long, hard time wondering who it was that was bravely fighting the advancing Russians. Soon we began to see batches of freshly captured prisoners.

One Prussian lancer was very amusing, always marveling at how well our cavalrymen rode. He galloped around every bush, every ditch, slowed down on the downhill gait, ours galloped straight ahead and, of course, caught him easily. By the way, many of our residents assure us that German cavalrymen cannot mount a horse themselves. For example, if there are ten men in a rider, then one of them first rides the nine and then sits down from the fence or stump himself. Of course, this is a legend, but a very distinctive one. I myself once saw a German fallen out of his saddle and run away, instead of getting back on his horse.

It was evening. The stars had already pierced the light mist in some places and we put out a guard and set out for the night. Our bivouac was an extensive manor house with cheese houses, an apiary, and model stables with very fine horses. Chickens and geese walked around the yard, cows mooed in closed rooms, and there were no people, not even a cattle-herder to let the tethered animals, drink. But we didn't look at it. The officers took a few front rooms in the house; the lower ranks got the rest. I had no difficulty in getting my own room, which belonged to some housemaid or lady's maid, judging by the cast of women's dresses, gaudy novels, and cheerful postcards; I chopped some wood, stoked the stove, threw myself on the bed in my overcoat, and fell asleep at once. I woke up in the middle of the night from the freezing cold. My stove went out, the window opened, and I went into the kitchen, dreaming of getting warm by the glowing embers.

And to top it off, I received some very valuable practical advice. To keep warm, I should never lie down in an overcoat, but only cover myself with it. The next day I was a patrolman. I rode in the fields, about three hundred paces from the highway, and it was my duty to look in many villages and farmsteads to see if there were any German soldiers, or even Landsturmists, that is men of seventeen to forty-three years of age. It was quite dangerous, somewhat complicated, but very exciting. At the first house I met an idiotic-looking boy, his mother assured me that he was sixteen, but he could just as easily have been eighteen or even twenty. Still, I left him, and in the next house, while I was drinking milk, a bullet slammed into the doorjamb about two inches from my head. At the parson's house I found only a Polish-speaking Litvinian maid, who explained to me that the owners had fled an hour before, leaving a cooked breakfast on the stove, and she urged me to take part in destroying it. In general, I often had to enter completely deserted houses, where coffee was boiling on the stove, on the table there was the beginning of knitting, an open book; I remembered about the girl who walked into the bear house, and kept waiting to hear a loud: "Who ate my soup? Who lay on my bed?"

Wild were the ruins of the town of Sh. Not a living soul. My horse shuddered as it made its way through the brick-strewn streets, past buildings with their insides torn out, past walls with gaping holes, past roofs ready to collapse at any moment. On the shapeless pile of rubble was the only surviving sign that read "Restaurant. What happiness it was to escape again to the expanse of fields, to see the trees, to hear the sweet smell of the earth.

In the evening we learned that the offensive would continue, but that our regiment would be transferred to a different front. Novelty always captivates a soldier but when I looked at the stars and breathed the night wind, I suddenly felt very sad to leave the sky, under which, after all, I had received my baptism of fire.

Chapter 3

Southern Poland is one of the most beautiful places in Russia. We drove eighty versts from the railroad station to the contact with the enemy, and I had time to admire it to my heart's content. There are no mountains there, a tourist attraction, but what does a plain dweller need mountains for? There are forests, there are waters, and it is quite enough. The forests are pine and sazhens, and passing through them, suddenly you see narrow, straight as arrows, the alleys full of green gloom with a shining gap in the distance, - like temples of gentle and thoughtful gods of ancient, still pagan Poland. There are deer and roe deer, golden-crowned pheasants with a hen's habit, and in the quiet nights you can hear the clucking and the breaking of the bushes by the wild boar. Rivers meander lazily among wide shoals of eroded banks; wide, with narrow isthmuses between them, lakes shine and reflect the sky like polished metal mirrors; near old mossy mills quiet dams with gently murmuring streams of water and some pink-red bushes, strangely reminding a man of his childhood. In such places, no matter what you do, whether you love or fight, everything seems significant and wonderful. Those were the days of great battles.

From morning till late at night we could hear the clatter of cannons, the ruins were still smoking, and here and there piles of inhabitants were burying the corpses of men and horses. I was assigned to the flying post at K station. Trains were already passing by it, though mostly under fire. Only the railroad workers remained there; they greeted us with marvelous cordiality. Four machinists fought over the honor of sheltering our small group. When at last one of them prevailed, the others came to visit him and exchange impressions. You should have seen their eyes burn with delight as they told us that shrapnel had exploded near their train and that a bullet had struck the locomotive. One could sense that only a lack of initiative prevented them from signing up as volunteers. We parted as friends, promising to write to each other, but are such promises ever kept?

Russian troops in Warsaw

On the next day, amidst the sweet idleness of the late bivouac, while reading the yellow books of the Universal Library, cleaning the rifle, or simply chatting with the pretty panniers, we were suddenly commanded to saddle up, and just as suddenly, at a variable gait, we passed fifty versts at once. One by one we passed sleepy little places, quiet and stately farmsteads, and old women in shawls thrown over their heads on the thresholds, murmuring: "Oh, Mother Bozka." As we rode out occasionally onto the highway, we listened to the thudding of countless hooves, like the surf of the sea, and guessed that other cavalry units were ahead and behind us, and that we had a big job ahead of us. The night was well past the halfway point when we bivouacked. In the morning we were replenished with ammunition and moved on. The place was deserted: some gullies, low spruces, hills. We formed a fighting line, assigned who would dismount and who would be the horse-driver, sent a detachment forward and waited. As we climbed the hill, hidden by the trees, I could see a space about a mile in front of me. Our outposts were scattered across it here and there. They were so well concealed that I only got a good look at most of them when, shooting back, they began to withdraw. Almost following them were the Germans. Three columns came into my sight, moving about five hundred paces apart. They were marching in thick crowds and singing. It was not any particular song or even our friendly "hurrah," but two or three notes alternating with fierce and sullen energy. I didn't immediately realize that the singers were dead drunk. It was so strange to hear this singing that I did not notice the roar of our guns or the gunfire or the frequent, pounding of the machine guns. The wild "ah... а... ah..." overpowered my consciousness. I could only see the clouds of shrapnel rising over the very heads of the enemy, the front ranks falling, the others taking their place and advancing a few paces to lie down and give room for the next. It was like the flood of spring water-the same slow and steady pace.

But now it was my turn to join the fight. The command was heard: "Get down... "sight eight hundred... squadron, fire," and I didn't think about anything else, just shot and loaded, shot and loaded. Only somewhere in the back of my mind I felt sure that everything would be all right and at the proper moment we would be ordered to attack or to mount the horses, and that we would make the blinding joy of the final victory closer.

Late at night we camped at the big manor. His wife boiled a quart of milk for me in the gardener's room, I roasted a sausage in lard, and my supper was shared by my guests: a freemen, who had just had his leg crushed off by a horse that had just killed him, and a vahmister with a fresh abrasion on his nose, who had been so scratched by a bullet. We were smoking and talking peacefully when a noncommissioned officer who happened to wander in informed us that a squadron was sending out a detachment. I examined myself carefully and saw that I had slept, or rather had slept in the snow, that I was well fed and warm, and that there was no reason for me not to go.

True, it was unpleasant at first to leave the warm and comfortable room for the cold and desolate courtyard, but this feeling was replaced by an exhilaration as we plunged the invisible road into the darkness, the unknown and the dangerous. The journey was a long one, and so the officer let us take a nap, for about three hours, in some hayloft. Nothing is so refreshing as a short nap, and in the morning, we were on our way quite awake, illuminated by a pale but still lovely sun. We were instructed to observe an area of four versts and report anything we noticed. The terrain was perfectly flat, and three villages were visible in front of us as if in the palm of our hands. One was occupied by us, the other two were unknown. We drove cautiously into the nearest village with our rifles in our hands, drove all the way through, and without finding any enemy, drank the steaming milk which was given to us by a pretty, chatty old woman. Then the officer took me aside and told me that he wanted to give me an independent assignment to be in charge of two sentries in the next village. A trifling errand, yet a serious one, considering my inexperience in the art of warfare, and above all the first in which I could show my initiative.

Who does not know that in any case, the initial steps are more pleasant than all the rest. I decided to march not in a lava line, that is, in a row, at some distance from each other, but in a chain, that is, one after the other. This way I put less danger to the men and had a chance to tell the trailhead something new quickly. We drove into the village and from there noticed a large column of Germans moving about two versts away. The officer stopped to write a report, and I drove on to clear my conscience. A steep bend in the road led to a mill. I saw a group of quiet inhabitants standing near it and, knowing that they were always running away, anticipating a clash in which they might get a shawl bullet, I trotted up to ask about the Germans. But as soon as we exchanged greetings, they scattered with distorted faces, and a cloud of dust rose in front of me and the distinctive crack of a rifle behind them. I looked back at the road I had just taken, and there was a bunch of horsemen and footmen in black, eerily alien overcoats staring at me in astonishment. Obviously, they had just spotted me. They were about thirty paces away. I realized that this time the danger was really great. The road to the turnoff was cut off for me, with enemy columns moving on the other two sides. I had no choice but to gallop straight at the Germans, but there was a ploughed field far out there that I could not gallop across, and I would be shot ten times before I left the range of fire. I chose the middle one and, rounding the enemy, raced in front of his front to the road our detachment had taken. It was a difficult moment of my life. The horse stumbled over frozen clods, bullets whizzed past my ears, exploded the ground in front of me and beside me, one scratched the bow of my saddle. I stared at my enemies. I could see their faces clearly, confused as they loaded, focused as they fired. A short, elderly officer was shooting at me with a revolver, strangely outstretched. The sound stood out in some kind of dissonance among the others.

Two riders jumped out to block my way, I drew my saber, they hesitated. Maybe they were just afraid of being shot by their own comrades. I remembered it all at that moment only with my visual and auditory memories, but I realized it much later. Then I only held my horse and muttered a prayer to the Mother of God, which I had immediately composed and immediately forgot when the danger had passed.

But here is the end of the arable field - why did people invent farming? - Here is the ditch which I take almost unconsciously, here is the smooth road on which I catch up at full speed with my passing-track. Behind him, unconcerned with the bullets, an officer is holding his horse. As he waits for me, he too moves to the quarry and says with a sigh of relief: "Well, thank God! It would have been awfully silly if you had been killed. I quite agreed with him. We spent the rest of the day on the roof of a lonely hut, chatting and looking through binoculars. The German column we had spotted earlier was hit by shrapnel and turned back. However, the trains were darting in a variety of directions. Occasionally they would collide with ours, and then the sound of gunfire would reach us. We ate boiled potatoes and took turns smoking the same pipe.

Chapter 4

The German offensive was suspended. It was necessary to investigate what points the enemy occupied, where he entrenches, where he simply places outposts. A number of patrols were sent out for this purpose, and I was part of one of them. On a gray morning we trudged along the main road. Entire convoys of refugees were pulling toward us. Men looked at us with curiosity and hope, children reached out to us, women wailed, sobbing: "Oh, Panichi, don't go there, you will be killed by the Germans". In one village the detachment stopped. I and two soldiers were to drive on and find the enemy. Our infantrymen were now at the roundabout, and a field of shrapnel stretched on, where the fighting had broken out and the Germans had withdrawn; a small folvar was black further on. We trotted toward it. To the right and to the left, on almost every square mile there were German corpses. I counted forty in one minute, but there were many more. There were wounded too.

Somehow, they suddenly began to move, crawled a few paces, and froze again. One was sitting at the very edge of the road, holding his head, rocking and moaning. We wanted to pick him up, but decided to do it on the way back. We rode safely to the folvarque. Nobody shot at us. But now we heard the blows of the spade on the frozen ground and some unfamiliar voice. We dismounted, and I, rifle in hand, crept forward to look out from behind the corner of the outermost barn. There was a small hill in front of me, and on the ridge of it the Germans were digging trenches. I could see them stopping to rub their hands and have a smoke, and I could hear the angry voice of a noncommissioned officer or an officer. To the left there was a grove to the dark, from behind which came the gunfire. That was where the field I had just passed was being fired upon. I still don't understand why the Germans didn't put up any picket in the fieldhouse itself. But there are more wonders in war than that. I was peering around the corner of the barn, taking off my cap to be mistaken for a curious "free man," when I felt a light touch from behind. I turned around quickly. A Polish woman with a haggard and sorrowful face was standing in front of me. She was handing me a handful of small, shriveled apples: "Take it, Mr. Soldier, I mean Dobrze, Zukerno". I could have been spotted every minute, shot at; bullets would have flown at her, too. Understandably, it was impossible to refuse such a gift. We made our way out of the folwark. Shrapnel burst more and more and on the road itself, so we decided to gallop back on our own. I hoped to pick up the wounded German, but a shell exploded low, low over him, and it was all over.

German military equipment

It was getting dark the next day, and everyone was scattered in the haylofts and barns of the big manor, when suddenly our platoon was ordered to assemble. Hunters were summoned to go on a night scouting patrol, a very dangerous patrol, as the officer insisted. Ten men came out at once; the rest, after stomping around, announced that they also wanted to go and were only ashamed to ask to go. Then it was decided that the platoon leader would appoint the hunters. And so, eight men were chosen, who were, again, more perky. I was one of them. We rode the horses to the Hussar guard. We dismounted behind trees, left three men as horsemen, and went to ask the Hussars how things were going. A moustachioed footman, hidden in a heavy shell crater, told us that enemy scouts had come out of the nearest village several times, sneaking across the field to our position, and had already fired twice.

We decided to venture into the village and, if possible, take some scouts alive. The full moon was shining, but fortunately for us it was hidden by clouds. We waited for one of these eclipses and, crouching down, ran towards the village, but not along the road, but in a ditch that ran alongside it. We halted at the roundabout. The detachment was to remain here and wait. The two hunters were to go through the village and see what was behind it. I and one of the reserve non-commissioned officers, formerly a courteous servant in some public office, now one of the bravest soldiers in a squadron considered to be in combat, went. He on one side of the street, I on the other. On the whistle we were to go back.

Here I am all alone, in the middle of a silent, lurking village, from the corner of one house I run over to the corner of the next. Fifteen paces to the side, I see a figure creeping in. It is my companion. I try to walk ahead of him out of ego, but I am too afraid to rush. I am reminded of the game of stealing sticks, which I always play in summer in the countryside. There is the same bated breath, the same cheerful awareness of danger, the same instinctive ability to sneak up and hide. And you almost forget that here, instead of the laughing eyes of a pretty girl, a playmate, you can only meet a sharp and cold bayonet pointed at you. Here is the end of the village. It's getting a little lighter, the moon breaking through the loose edge of the clouds; I see the low, dark mounds of trenches in front of me and immediately remember, as if photographing them. After all, that's what I came here for. At the same minute in front of me looms a human figure. It is looking at me and whistling softly, in some peculiar, obviously conventional way. It is the enemy, a clash is inevitable. There is but one thought in me, living and powerful as passion, as frenzy, as ecstasy: I am his or he is mine! He hesitantly raises his rifle, I know I must not shoot, there are many enemies nearby, and I rush forward with my bayonet down. In a moment there is nobody in front of me. Maybe the enemy has crouched on the ground, maybe he has bounced away. I stop and stare. Something is black. I move closer and touch it with my bayonet, no, it's a log. It's black again. Suddenly there is an unusually loud shot from my side and the bullet knocks hurtfully close to my face. I turn around, a few seconds at my disposal while the enemy changes the cartridge in the rifle magazine. But already from the trenches I hear the nasty snarl of tra-tra-tra shots, and the bullets whistle, whine, screech. I ran to my squad. I was not afraid.

I knew the night shot was not valid and I just wanted to do the right thing and do it better. So, when the moon lit up the field, I threw myself to nothing, and so crawled away into the shade of the houses, it was almost safe to walk there. My comrade, the non-commissioned officer, returned at the same time as me. He had not yet reached the edge of the village when the shooting started. We returned to the horses. We exchanged impressions in the lonely hut, ate bread and bacon, the officer wrote and sent a report, and we went out again to see if anything could be arranged. But alas! - The night wind had torn the clouds to shreds and the round, reddish moon was down over the enemy's positions, blinding our eyes. We were visible as if in the palm of our hands; we could see nothing. We were ready to cry in frustration and, in spite of fate, crawled towards the enemy. The moon might have hidden again, or we might have run into a stray scout! None of this happened, we were just shot at and we crawled back cursing the moon effects and the cautiousness of the Germans. Nevertheless, the information we got came in handy, we were thanked, and I received the George Cross for that night.

The next week was comparatively quiet. We saddled up while it was still dark, and on the way to the position I admired every day the same wise and bright doom of the morning star against the water-colored, snowy dawn. In the afternoon we lay at the edge of a large pine forest and listened to the distant cannon fire. The pale sun was warming slightly, and the ground was thickly strewn with soft, strangely smelling needles. As always in winter, I longed for the life of summer nature, and it was so sweet, peering very closely into the bark of the trees, to notice in its rough folds some nimble worms and microscopic flies. They were hurrying somewhere, doing something, despite the fact that it was December.

Life smoldered in the forest, just as a timid, smoldering light smolders inside a black, almost cold firebrand. Looking at it, I felt with all my being that big, strange birds and small birds with crystal, silver and crimson voices would come back here again, that stuffy-smelling flowers would bloom, and that the world would be filled with stormy beauty for the solemn celebration of the witchy and sacred Ivan's Night.

Sometimes we would stay in the woods all night. Then, lying on my back, I would gaze for hours at the innumerable stars, clear from the frost, and amuse myself by connecting them in my imagination with golden threads. At first it was a series of geometric drawings, like an unfolded Kabbalah scroll. Then I began to distinguish, as on a woven golden carpet, various emblems, swords, crosses, and chalices in incomprehensible combinations that made no sense to me, but were full of inhuman meaning. Finally, the celestial beasts of heaven loomed up distinctly. I could see the Big Dipper, muzzle down, sniffing at someone's trail, and the Scorpion moving its tail, looking for someone to sting. For a moment I was inexpressibly afraid that they would look down and see our Earth there. Because then it would immediately turn into a huge piece of matte white ice and fly out of orbit, infecting other worlds with its horror. Then I would whisper to my neighbor for some tobacco, roll up a cigarette and smoke it in my hands with pleasure: to smoke otherwise would be to give away our goodwill to the enemy.

At the end of the week a joy awaited us. We were taken to the army reserve, and the regimental priest held a service. There was no compulsion to go to it, but there was not a single man in the whole regiment who did not go. In the open field a thousand men lined up in a slender rectangle, in the center of which the priest in a golden robe spoke eternal and sweet words, serving a prayer service. It was like the field prayers for rain in remote, distant Russian villages. The same immense sky instead of a dome, the same simple and native, focused faces. We prayed well that day.

Chapter 5

It was decided to equalize the front by withdrawing thirty versts and the cavalry was to cover this withdrawal. Late in the evening we approached the position, and at once the spotlight from the enemy's side descended upon us and slowly froze, like the gaze of an arrogant man. We pulled away; it, gliding across the ground and through the trees, followed us. Then we galloped in loops and started for the village, while he poked here and there, hopelessly looking for us. My platoon was sent to the headquarters of the Cossack division to serve as a liaison between it and our division. Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace makes fun of staff officers and gives preference to drill officers. But I have not seen a single HQ that left before shells started tearing over its premises.

The Cossack HQ was stationed in a large place called R. The inhabitants had fled the day before, the carts were gone, the infantry too, but we sat for more than a day listening to the slowly approaching firing - it was the Cossacks holding up the non-commissioned chains. The colonel, tall and broad-shouldered, ran to the telephone every minute and shouted merrily into the receiver: "Well... fine... "Hold on a little longer... it's going well..." And from these words the confidence and calmness, so necessary in a fight, poured out over all the folvarks, ditches and copses, occupied by the Cossacks. The young divisional commander, the bearer of one of the loudest surnames in Russia, occasionally went out on the porch to listen to the bullet-meters and smiled at the fact that everything was going as it should. We lancers conversed with the sedate, bearded Cossacks, with that exquisite courtesy with which cavalrymen of different units treat each other.

By noon word had reached us that five men of our squadron had been taken prisoner. By evening I had seen one of these prisoners, and the others had piled out in the hayloft. That's what happened to them. There were six of them in the guard. Two stood on the watch and four sat in the hut. The night was dark and windy, and the enemies crept up on the sentry and overturned him. The sub-chasok gave a shot and rushed to the horses, they toppled him too. At once fifty men burst into the yard and started shooting through the windows of the house where our picket was located. One of ours jumped out and, working his bayonet, broke through to the woods, the others followed him, but the one in front fell, stumbling on the threshold, and his comrades fell on him. The enemy, who were Austrians, disarmed them and under escort of five men also sent them to headquarters. The ten men found themselves alone, without a map, in complete darkness, among a jumble of roads and paths. On the way, an Austrian non-commissioned officer kept asking us in broken Russian where the Cossacks were. Our men were frustrated and finally announced that "kozi" was where they were being led, away from enemy positions.

This had an extraordinary effect. The Austrians stopped and began to argue animatedly about something. It was clear that they did not know the way. Then our non-commissioned officer tugged at the sleeve of the Austrian and said encouragingly "Never mind, let's go, I know where to go." Let's go, slowly bending toward the Russian positions. In the whitish twilight of the morning, gray horses flashed among the trees - the Hussars' detachment. "Here come the goats!" - exclaimed our noncommissioned officer, snatching his rifle from the Austrian. His comrades disarmed the others. The hussars laughed a good deal when the lancers, armed with Austrian rifles, approached them, escorting their newly captured prisoners. Again, they went to headquarters, but this time to Russian headquarters. On the way they met a Cossack. "Well, uncle, show yourself," ours asked. He pulled his hat over his eyes, shook his beard, shrieked and let his horse gallop. I had to encourage and reassure the Austrians for a long time afterwards.

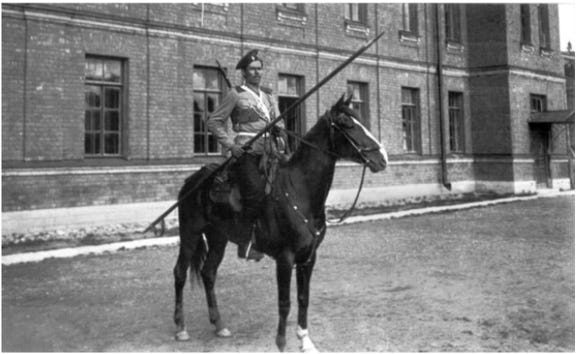

Lower ranks of the Life Guards Hussar Regiment in full dress uniform, 1910s.

Uryadnik of Siberian fifteen-hundred of the 3rd Hundred Life Guards of the Free Cossack Regiment. 1914 г.

The next day at the headquarters of the Cossack division, and he and I moved four versts away, so that we could see only the factory chimneys of the place R. I was sent with a report to the headquarters of our division. The road was through R., but the Germans had already approached it. But I took the road anyway, in case I could get through. The officers of the last of the Cossack detachments coming towards me stopped me with a question - freedman, where to? - and when they recognized me, they shook their heads in doubt. Behind the wall of the outermost house stood a dozen hasty Cossacks with rifles at their tops. "You can't go through," they said, "that's where they're firing. Just as I moved forward, shots rang out, bullets jumped. Crowds of Germans were moving toward me along the main street, and the noise of others could be heard in the alleys. I turned, and the Cossacks followed me, firing several volleys. On the road an artillery colonel, who had already stopped me, asked:

- Well, haven't you passed?

- No, the enemy is already there.

- Did you see it yourself?

- Yes, I saw it myself. - He turned to his lieutenants: "All guns are firing on the place.

Kuban Cossacks in May 1916

I drove on. However, I still had to make my way to headquarters. Looking over an old map of the county that I happened to have, consulting with a comrade, who always sends two men with a report, and asking the locals, I took a circuitous route through the woods and swamps to my destination village. We had to move along the front of the advancing enemy, so it was no surprise that as we left a village where we had just drunk milk, we were cut off at right angles by an enemy patrol. He evidently mistook us for sentries, for instead of attacking us in a mounted formation he began to dismount to fire. There were eight of them, and we turned behind the houses and started to leave. When the firing ceased, I turned around and saw riders galloping behind me at the top of the hill; they were following us; they realized there were only two of us. At that time gunshots were heard from the side again, and three Cossacks - two young, bony fellows and one bearded man - rushed straight at us. We ran into each other and held our horses.

- What have you got there? - I asked the bearded man.

- Foot scouts, fifty or so. What about you?

- Eight mounted.

He looked at me, I looked at him, and we understood each other. We were silent for a few seconds. - Shall we go? - He said suddenly, as if reluctantly, and his eyes lit up.

The cheekbones of the fellows who had been looking at him anxiously shook their heads and started at once to get the horses ready. We had barely climbed the hill we had just left when we saw the enemy coming down the opposite hill. My ears were burned by a screech or a whistle that at times sounded like the sound of an engine and the hiss of a large snake, and I saw the backs of the rushing Cossacks and dropped the reins and worked my spurs furiously, remembering only with the exertion of my will that I should draw my sword. We must have looked very determined, for the Germans were on the run without any hesitation. They drove desperately, and the distance between us hardly decreased. Then the bearded Cossack put his sword in its scabbard, raised his rifle, fired, missed, fired again, and one of the Germans raised both hands, shook himself, and flew out of the saddle like a tossed-up man. In a minute we were rushing past him. But everything comes to an end! The Germans turned abruptly to the left and bullets were pouring towards us. We ran into the enemy's chain. But the Cossacks had not turned before they had caught the dead German's horse that had been running around in disarray. They chased after it, disregarding the bullets, as if in their native steppe. "Baturin will need it," they said, "he had a good horse killed yesterday. We parted behind the bump, shaking hands amicably. I found my HQ only five hours later, and not in the village, but in the middle of a forest clearing on low stumps and piled tree trunks. They, too, had already withdrawn under enemy fire.

I returned to the headquarters of the Cossack Division at midnight. I ate cold chicken and went to bed, when suddenly there was a commotion, the order to saddle up was heard, and we took off from the bivouac on alarm. It was pitch-black darkness. Fences and ditches loomed up only when the horse bumped into them or fell through. In my sleep I couldn't even make out the direction. When branches bruised my face, I knew we were in the woods, and when water splashed at my feet, I knew we were wading through rivers. At last, we came to a halt at a large house. We parked the horses in the courtyard, went into the shed, lit the lamps... And we were startled when we heard the thundering voice of a fat, old xeno, who came out to meet us in his undergarments and a brass candlestick in his hand.

"What is this," he shouted, "I have no rest even at night! I haven't slept, I still want to sleep!" We mumbled a timid apology, but he jumped forward and grabbed the sleeve of the senior officer: "This way, this way, this is the dining room, this is the living room, have your soldiers bring straw. Yuzia, Zosya, get the pillows for the pans and get clean pillowcases. When I woke up, it was already light. The staff in the next room was going about their business, taking reports and sending out orders, while in front of me the master was raging: "Get up quick, the coffee will get cold, everybody has been drunk for a long time!" I washed my face and sat down to my coffee. The priest sat against me and questioned me sternly:

- Are you a volunteer? - A volunteer.

- What did you do before?

- I was a writer.

- A real one?

- I can't tell. I used to publish in newspapers and magazines and books. - Do you write any notes now?

- I do.

His eyebrows drew apart, his voice soft and almost pleading:

I do. - So, please, write about me, how I live here, how you get to know me.

I sincerely promised him that.

- No, you will forget. Yuzia, Zosya, a pencil and paper!

And he wrote down for me the name of the county and the village, his first and last name. But is there anything to hold on to in the cuffs of the sleeve where cavalrymen usually hide all sorts of notes, business, love, and just like that? In three days, I had lost everything, including this one. And now I am deprived of the opportunity to thank the Honourable Father (I do not know his last name) from the village (I forget its name), not for a pillow in a clean pillowcase, not for coffee and delicious muffins, but for his deep tenderness under his stern manners and for the fact that he reminded me so vividly of those wonderful old hermits who quarrel and make friends with the night travelers in the forgotten but once beloved novels of Walter Scott.

Chapter 6.

The front was leveled. Here and there the infantry was repulsing the enemy, who imagined he was advancing on his own initiative; the cavalry was engaged in intensive reconnaissance. Our detachment was assigned to observe one of these battles and report developments and incidents to headquarters. We caught up with the infantry in the woods. Small gray soldiers with their huge bags were walking at random, lost against the background of bushes and pine trunks. Some were snacking, others were smoking, and the young warrant officer was waving his cane merrily. It was a tried and glorious regiment that went into battle as if it were an ordinary field work, and one felt that at the right moment everyone would be in their places without confusion, without turmoil, and everyone knew perfectly well where he ought to be and what to do.

The battalion commander, riding on a shaggy Cossack horse, said hello to our officer and asked to know if there were any enemy trenches in front of the village he was advancing on. We were very glad to help the infantry, and a non-commissioned officer's detachment was sent out at once, which I led. The terrain was surprisingly comfortable for the cavalry: hills from behind which one could show oneself unexpectedly, and ravines through which one could easily evade. As soon as I reached the first hill a shot rang out - it was only the enemy's secret. I took a right and drove on. Through the binoculars I could see the whole field up to the village; it was empty. I sent one man with the report and myself and the other three were tempted to scare the secret that fired at us. In order to find out exactly where it lay, I peeked out of the bushes again, heard another shot and then, marking a small hill, raced to it, trying to remain invisible from the village. We rode to the hill - no one there. Was I mistaken?

No, one of my men dismounted and picked up a brand-new Austrian rifle; another spotted the freshly chopped branches on which the Austrian secret had just been laid. We climbed the hill and saw three men running as fast as they could. They must have been mortally frightened by the unexpected mounted attack, because they did not shoot or even turn around. It was impossible to follow them, we would have been fired upon from the village, and besides, our infantry was already out of the forest, and we could not stay in front of its front. We went back to the crossing and, sitting on the roof and the rambling elms of the old mill, watched the fight.

Cossack of the Life Guards Cossack Regiment

(end of this fragment.)

.