From Rus to Russia, condensed

From Rus to Russia / L. N. Gumilev - "MTF", 1992 - (Historical Chronicles)

This is another condensed version which can be likened to the Yevtushenko book below. This is because the first half explains theory of ethnogenesis and the second part talks about Russian origins, including wide ranging causality as a background. It is just a taste of Ancient Rus, because it is so much shortened. But reading these 27 pages could be a preamble to reading the full Yevtushenko book. Come here first.

The outstanding Russian historian and geographer L.N. Gumilev's book is devoted to the history of Russia from the times of Rurik to the reign of Peter I in the full book, all events and deeds of historical persons are explained from the position of ethnogenesis passionary theory, developed by the author. The book is written in a lively, figurative language, very entertaining and understandable, so a huge amount of factual material is absorbed without any effort on the part of the reader. It is thanks to these qualities, the book was recommended by the Ministry of Education of Russia as a textbook for high school students. True lovers of Russian history will also enjoy reading this extraordinary work.

[I have also translated this full version of this book, but I have not yet edited it. This shorter version Rus to Rusia is 27 pages. The full book is over 500 pages, but it’s half that amount of text because it is fully illustrated with about 300 medieval woodcuts. Therefore it is a beautiful book, and the reason why I did it. I sincerely doubt that I will post it here though, because adding hundreds of images would be a daunting task.]

© Gumilev L. N., 1992 © MTF, 1992, UDC 94(47) BBC 63.3(2)

There are a few examples from the birth of the Russian state here in the 2nd half. But the full book has an unimaginable amount of details. Read this first, but for now if you want more detail of the period, I have uploaded this other book:

It is a fast paced run-through of 1,000 years of Russia.

Table of contents

(Page numbers are from the Russian, but I think I will omit them, for 27 pages.)

Instead of the Preface 1

Part One 12

Chapter I 12

Two Europe 12

Goths 13

Huns and “Huns” 14

Birth of the Kiev Power 18

Chapter II 20

In the Lower Volga 20

Aliens from the South 23

Power and Money 25

End of Introduction Fragment. 27

Lev Gumilev From Rus' to Russia Essays on Ethnic History

Instead of the preface.

Today in our country we observe an unprecedented growth of interest to history. What causes it, what is it based on? Often, we can hear that, confused in the problems of today, people turn to history in search of a way out of difficult situations. As they used to say in the old days, "for instructive examples”. True, but in this case the interest in history shows something else: modernity and history are perceived by most of our compatriots as fundamentally different, incompatible temporal elements. Often history and modernity simply collide: "We are only interested in modernity and only need to know about it!" Similar opinions can be heard in scholarly debates, over tea, and even in bazaar bickering.

There is indeed some basis for contrasting modernity and history. The word "history" itself implies "what came before," "what is not today," and so historical scholarship is inconceivable without taking into account the changes separating "yesterday" from "today”. The number and scale of these changes may be insignificant, but outside of them history does not exist.

By saying "modernity," on the contrary, we are referring to a certain familiar and seemingly stable system of relations within and outside the country. It is this habitual, familiar, almost unchanging and understandable, that is usually contrasted with history - something intangible, and therefore incomprehensible. And what follows is simple: if we cannot explain the actions of historical figures from a modern point of view, it means they were uneducated, had numerous class prejudices and generally lived without the benefits of scientific and technological progress. So much the worse for them!

And it doesn't occur to anyone that, at one time, the past was also modern. So the apparent permanence of modernity is a deception, and it is not different from history. All the lauded present is just a moment which immediately becomes the past, and it is no easier to return to this morning than to the age of the Punic or Napoleonic wars.

Paradoxically, it is modernity that is imaginary, and history that is real. It is characterized by the change of epochs, when the balance of peoples and powers suddenly breaks down: small tribes make great campaigns and conquests, and mighty empires are powerless; one culture replaces another, and yesterday's gods turn out to be worthless idols. To understand the patterns of history, generations of true scholars have worked, and their books are still read today.

So history is a constant change, a perpetual rearrangement of seeming stability. When we look at a certain territory at any given moment, we see a photographic image - a relatively stable system of interconnected objects: geographical (landscapes), socio-political (states), economic, ethnic. But as soon as we start to study not one state, but their multitude, i.e. the process, the picture changes dramatically and begins to resemble a child's kaleidoscope rather than a strict cartographic image with dry inscriptions.

Let us look, for example, at Eurasia at the beginning of the first century A.D. The western extremity of the great Eurasian continent was occupied by the Roman Empire. This power, which grew out of a tiny town founded by a tribe of Latins eight centuries B.C., absorbed a great many.

The empire was organically incorporated with Cultural Hellenes, who remained generally loyal subjects for a very long time, and were organically incorporated into the empire. With the Germans, who lived across the Rhine, the Romans, on the other hand, began to fight. Although their victorious commanders Germanicus and the future emperor Tiberius led their legions as far as the Elbe, by the middle of the first century AD the Romans had given up conquering the Germans.

To the east of the Germans lived Slavic tribes. The Romans called them, like the Germans, barbarians, but in reality, they were an entirely different people, not at all friendly with the Germans.

Farther east, in the vast steppes of the Black Sea and Kazakhstan, we find at this time a people which bear little resemblance to the European, the Sarmatians. And on the border with China, in what is now Mongolia, roamed a people of the Xiongnu (Huns).

The eastern edge of Eurasia, as well as the western edge, was occupied by a huge power - the Han Empire. The Chinese, like the Romans, considered themselves a cultured, civilized people living among the barbarian tribes surrounding them. The Romans and Chinese had little or no contact with each other, but there was still a connection between them. A thread between the two empires, invisible but strong, was the Great Silk Road. Chinese silk flowed along it to the Mediterranean, turning into gold and luxury goods.

However, the Chinese and Romans did not meet on the Great Silk Road either, for neither one nor the other went with caravans. It was the Sogdians - the inhabitants of Central Asia - and the Jews, who were engaged in international trade. Under their leadership, caravans crossed the vast expanses of the continent. And on its outskirts, in Roman fortresses and on the Great Wall of China, sentinels guarded the peace of "civilized" empires day and night. (Each trip took over 200 days.)

Let us ask ourselves a simple question: what has prevented this well-functioning static system of relations from surviving to our time? Why don't we see the Romans or the Great Silk Road today? At the end of the first and beginning of the second century A.D. the situation changed radically; many nations which until then had been living peacefully in their usual conditions, were on the move.

By sending the Goths, the inhabitants of Scandinavia, into the estuary of the Vistula River, the Great Migration of Peoples began which in the fourth century led to the fall of the unified Roman Empire. This is when the Slavs also began their migrations, leaving the area between the Vistula and the Tisza, and later spreading from the Baltic in the north, to the Adriatic and the Balkans in the south, and from the Elbe in the west to the Dnieper in the east.

The Dacian tribe that occupied the territory of modern Romania went to war with Rome and it took the Empire twenty years of fighting to defeat this people using the entire Mediterranean, with the military and statesmanship of Emperor Trajan.

From the Christian communities that had emerged in Syria and Palestine, a new ethnos had by this time emerged, an "ethnos according to Christ". The bearers of the once persecuted doctrine managed not only to preserve it, but to make it the official ideology in one part of the disintegrating empire. Thus a new, Christian power, Byzantium, emerged as a counterbalance to the dying Western Rome, Hesperia.

In the same Palestine a hotbed of resistance to Roman domination emerged. A small people, the Jews, left their historic homeland after two rebellions that were brutally suppressed by the Romans. But the emergence of a Jewish diaspora and the preaching of Christianity had the effect of strengthening Eastern religions in the heart of the Empire and its provinces.

Not only the Near East, but also the Far East became a source of trouble for Rome at this time. A branch of the Xiongnu left the steppes of Mongolia and ended up in Europe as a result of unparalleled migration. Already in the fourth century their descendants crushed the kingdom of the Goths and almost destroyed the Roman Empire itself.

Thus, if we try to imagine Eurasia in the 5th to 6th centuries, we will see a very different picture from the 1st century, with new empires on the outskirts of the continent, with very different peoples wandering the expanses of the Great Steppe.

The entire history of mankind consists of a series of such changes. Is it possible that the change of empires and kingdoms, faiths and traditions have no inner regularity, but is the chaotic inexplicable? Since ancient times, inquiring people (and there have always been those) have sought answers to this question, to understand and explain the origins of their history. The answers have naturally varied, for history is multifaceted: it can be a history of socio-economic formations or a military history, that is, a description of campaigns and battles; a history of technology or culture; a history of literature or religion. These are all different disciplines of history.

And so, some - historians of the legal school - studied human laws and principles of government; others - Marxist historians - viewed history through the prism of the development of productive forces; still others relied on individual psychology, and so on.

Is it possible to imagine human history as the history of peoples? Let us try to assume that within the Earth, space is by no means homogeneous. And space is the first parameter which characterizes historical events. Even primitive man knew the borders of his territory, the so-called nourishing and hosting landscape in which he, his family and his tribe lived.

The second parameter is time. Every historical event takes place not only somewhere, but sometime. The same primitive people were fully aware not only of "their place" but also of the fact that they had fathers and grandfathers and would have children and grandchildren. So, temporal coordinates exist in history along with spatial coordinates.

But in history there is another, no less important parameter. From the geographical point of view, all humanity should be regarded as the anthroposphere - one of the Earth's shells, connected with the existence of Homo sapiens. Humanity, while remaining within this species, has the remarkable property of being a mosaic, that is, it is composed of representatives of different peoples, ethnoses in modern parlance. It is within the framework of ethnoses in contact with each other that history is made, for each historical fact is the heritage of the life of a particular people. The presence in the Earth's biosphere of these particular entities - ethnic groups - constitutes the third parameter characterizing the historical process.

Ethnoses, existing in space and time, are actors in the theater of history. Hereafter, when we speak of ethnos, we will refer to a collective of people that contrasts itself with all other similar collectives, not out of conscious calculation but out of a sense of complementarity - a subconscious sense of mutual sympathy and commonality between people that determines the "us versus them" opposition and the division into "insiders" and "outsiders.

Each such collective, in order to live on Earth, has to adapt to the conditions of the landscape within which it has to live. The ties of the ethnos with the surrounding nature give rise to the spatial relationship of the ethnos with each other. However, it is natural that the members of an ethnos, living in their landscape, can adapt to it only by changing their behavior and assimilating some specific rules of behavior - stereotypes. Learned stereotypes (historical tradition) constitute the main difference between the members of one ethnos and another.

In order to describe their historical tradition, members of an ethnic group need a system of time reference. The easiest thing to do is to consider time cycles. A simple observation shows that day and night form a repeating cycle, the day. Likewise, the seasons, when they alternate, make up a larger cycle, the year. Because of this simplicity and obviousness, the first-time people knew how to count time, and still use it today, was the cyclic count.

The very origin of the Russian word "time", (one of the roots of the words "twirl" and "spindle", is connected with the idea of the cyclic nature of time).

In the East, for example, was invented a system of counting time, in which each of the 12 years is the name of one or another animal, represented by a particular color (white - metal, black - earth, red - fire, blue-green - vegetation). But since the ethnos lives for a very long time, neither the annual cycle nor even the twelve-year cycle of the Oriental peoples was sufficient to describe the events stored in the memory of the people.

In search of a way out of this impasse, the linear measurement of time, which counts from a certain moment in the historical past, began to be applied. For the ancient Romans, this date was the foundation of Rome; for the Hellenes, it was the year of the first Olympics. Muslims count years from the Hijra, the flight of the prophet Mohammed from Mecca to Medina. Christian chronology, which we use, counts from the Nativity of Christ. All we can say about linear time is that, unlike cyclical time, it underlines the irreversibility of time.

In the East there is another way of knowing and calculating time. Here is an example of such a reckoning. A princess of the Southern Chinese Cheng dynasty, destroyed by the Northern Sui dynasty, was taken captive. She was given as a wife to a Turkic khan who wanted to become related to the Chinese imperial family. The princess was bored on the steppes and composed poetry. One of her poems goes like this:

Preceded by glory and reverence of trouble,

For the world's laws are circles on the water.

The tower and the pond Will be smoothed over in time,

The glory and the splendor will die.

Though now we have riches and luxuries,

The hour of serenity is always short-lived.

The cup of wine has not drunken us for ages.

The lute's strings ring and fade.

I was a tsar's daughter,

And, now I am in a nomadic horde.

I've wandered without shelter and alone at night,

I've had delight and despair within me.

The perversity reigns in the land from time immemorial,

Examples you meet, wherever you look,

And the song that was sung in the old years,

Exile's heart is always disturbed.

Here the passage of time is seen as an oscillating movement, and certain time segments are distinguished according to their eventfulness. At the same time, large discrete "sections" of time are created. The Chinese called all this with one easy word: "vicissitudes.

Each "vicissitude" occurs at some point in historical time and, having begun, inevitably ends and is replaced by another "vicissitude. This sense of discreteness (discontinuity) of time helps to record and understand the course of historical events, their interconnection and sequence.

But when speaking of discontinuous time, linear or cyclical time, we must remember that we are talking only about man-made reference systems. The single absolute time we calculate remains a reality, not a mathematical abstraction, and reflects the historical (natural) reality.

Thus, discontinuous time is equally applicable to both human history and the history of nature. Well-described historical geology operates with eras and periods, in each of which the Earth's biosphere had a particular character. These are either the "wet" Carboniferous, with its abundance of large amphibians, or the "dry" Permian, with large reptiles living near bodies of water. In the three periods of the Mesozoic era: the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous, new flora and fauna emerged each time.

The Ice Age altered the Earth's flora and fauna once again. Prior to that time, Africa was inhabited by Australoptic species that vaguely resembled modern humans. After the Ice Age, Neanderthal Man appeared, with his oversized head and strong, stocky torso. Under circumstances unknown to us, the Neanderthals disappeared, to be replaced by modern Homo sapiens. In Palestine there are material traces of a clash between two types of humans: Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. In the caves of Schul and Tabun on Mount Carmel the remains of mixtures of the two species have been discovered. It is difficult to imagine the conditions for the emergence of this hybrid, especially considering that Neanderthals were cannibals. In any case, the new, mixed species proved to be non-viable.

So, the Neanderthals disappeared, and in our time, the Earth is populated by people, although of five different races, but belonging to the same species. Consequently, we have the right to consider that there is no direct continuity between Neanderthals and modern humans. But in the same way there is no continuity between Cro-Magnon mammoth hunters and ancient Celts, between Romans and Romanians, between Huns and Magyars.

In the history of ethnoses (peoples), as in the history of species, we are confronted with the fact that from time to time there is an absolute breakdown in certain parts of the Earth, when old ethnoses disappear and new ones appear. The Philistines and Chaldeans, the Macedonians and the Etruscans belong to antiquity. They are gone now, but once there were no Englishmen and Frenchmen, Swedes and Spaniards. So, ethnic history consists of "beginnings" and "endings.

But where and why do these new communities arise, suddenly beginning to separate themselves from their neighbors? "Eh no, we know you: you are Germans and we are French!"? It is clear that any ethnic group has an ancestor, not even one, but several. For example, for Russians the ancestors were ancient Russians, people from Lithuania and the Horde, and local Finno-Ugric tribes. However, the establishment of an ancestor does not exhaust the problem of the formation of a new ethnos. There are always ancestors, but ethnoses are formed quite rarely, both in time and in space. It would seem that there is no answer to this question, but let us remember that a hundred years ago there was no answer to the question about the origin of species.

In the last century, during the heyday of evolutionary theory, both before and after Darwin, it was believed that particular races and ethnic groups evolved out of a struggle for existence. Today, this theory is of little use to anyone, since a great deal of evidence points in favor of a different concept, the theory of mutagenesis.

According to this theory, every new species emerges as a consequence of a mutation - a sudden change in the gene pool of living beings that occurs under the influence of external conditions in a certain place and at a certain time. Of course, the presence of mutations does not cancel the intraspecific process of evolution: if the traits that appeared increase the viability of the species, they reproduce and are fixed in the offspring for a long enough time. If this is not the case, their carriers die out after a few generations. The theory of mutagenesis agrees well with the known facts of ethnic history. Let us recall the already mentioned example of migrations in the I-II centuries A.D. The powerful movement of new ethnic groups was relatively short-lived and took place only in a narrow band from southern Sweden to Abyssinia. But it was this movement that destroyed Rome and changed the ethnic map of the entire European Mediterranean.

___________________

Consequently, we can also hypothetically relate the beginning of ethnogenesis to the mechanism of mutation, which results in an ethnic "push" that then leads to the formation of new ethnoses. The process of ethnogenesis is connected with a quite definite genetic trait. Here we introduce a new parameter of ethnic history - passionarity. Passionarity is a trait that arises as a result of a mutation (a passionate impulse) and forms within a population a certain number of people with an increased propensity for action. We will call such people passionarians.

Passionaries strive and are capable of changing things around them. They are the ones who organize distant campaigns from which few return. They fight for the conquest of the peoples surrounding their own ethnos, or, conversely, fight against the invaders. Such activities require an increased capacity for exertion, and any effort by a living organism involves the expenditure of some kind of energy. This type of energy was discovered and described by our great compatriot Academician V.I. Vernadsky and called by him the biochemical energy of living matter of the biosphere.

The mechanism of the connection between passionarity and behavior is very simple. Usually people, as living organisms, have as much energy as they need to sustain life. If the human body is able to "absorb" more energy from the environment than it needs, it forms relationships with other people and connections that allow it to use this energy in any of the chosen directions. It is possible to create a new religious system or scientific theory, build a pyramid or the Eiffel Tower, etc. Passionaries act not only as direct doers, but also as organizers. Putting their surplus energy into the organization and management of fellow tribesmen at all levels of the social hierarchy, they develop, albeit with difficulty, new stereotypes of behavior, impose them on everyone else, and thus create a new ethnic system, a new ethnos visible to history.

But the level of passionarity in an ethnos does not remain unchanged. Ethnos, having emerged, goes through a series of regular phases of development that can be likened to different ages of man. The first phase is the phase of the ethnos' passionary rise, caused by a passionary impulse. It is important to note that old ethnoses, on the basis of which a new ethnos emerges, join together as a complex system.

Subethnic groups that are sometimes dissimilar create a new whole, fused by passionary energy, which expands and subjugates territorially close peoples. This is how an ethnos emerges. A group of ethnic groups in one region creates a super-ethnos (for example, Byzantium is a super-ethnos which appeared as a result of the shock in the 1st century A.D. and consisted of Greeks, Egyptians, Syrians, Georgians, Armenians, Slavs and existed till the 15th century). As a rule, the life expectancy of an ethnos is the same: from the moment of the shock to its complete destruction it lasts about 1,500 years, except for those cases when aggression by foreign tribesmen disrupts the normal course of ethnogenesis.

The greatest rise of passionarity, the acmatic phase of ethnogenesis, causes people to strive not to create integrity, but, on the contrary, to "be themselves": not to obey the common rules and to reckon only with their own nature. Usually, this phase in history is accompanied by such internal rivalries and massacres that the course of ethnogenesis is temporarily halted.

Gradually, the massacre causes the passionary charge of the ethnos to diminish, as people physically exterminate one another. Civil wars break out, a phase that we will call the fracture phase. It is usually accompanied by an enormous dissipation of energy, crystallized in monuments of culture and art. But the highest blossoming of culture corresponds to the decline of passionarity, not to its rise. This phase usually ends in bloodshed; the system wipes out excessive passionarity, and apparent equilibrium is restored in society.

Ethnicity begins to live "by inertia," thanks to acquired values. Let's call this phase Inertia. Once again, people are mutually subordinated to one another, large states are formed, and material wealth is created and accumulated.

The passionarity gradually dries up. When the energy in the system becomes scarce, the leading position in society is taken by sub-passionarians – (destroyers, the anti-system), people with reduced passionarity. They seek to destroy, and profit by, not only restless passionaries, but also hard-working harmonious people.

The phase of obscuration in which the processes of disintegration in the ethno-social system become irreversible. Everywhere people are dominated by sluggish and selfish people, guided by a consumerist psychology. And after the sub-passionarians have eaten up and drunk everything of value that has survived from heroic times, the last phase of ethnogenesis - the memorial phase - begins, when the ethnos retains only the memory of its historical tradition. Then memory also disappears: a time of equilibrium with nature (homeostasis), when people live in harmony with their native landscape and prefer to the great intentions of everyday life. In this phase, people's passionariness only suffices to maintain their ancestral economy.

A new cycle of development can only be triggered by another passionate push, in which a new passionate population emerges. However, this new population does not reconstruct the old ethnos, but creates a new one, giving rise to another round of ethnogenesis, a process thanks to which, Mankind does not disappear from the face of the Earth. (See if you can make sense out of this chart? But it just means that in the different stages he mentions, the level of personal energy (passionarity), rises and falls.)

Rki is the level of the system's passionary tension. The qualitative characteristics of this level ("sacrifice," etc.) should be regarded as a kind of averaged "evaluation" of ethnos representatives. At the same time there are people within the ethnos who have other characteristics noted in the figure, but one type of people dominates.

i is the index of the level of the system's passionary tension, corresponding to a certain imperative of behavior: i = -2, -1, -6; when i = 0 the level of the system's passionary tension corresponds to homeostasis;

k is the number of sub-ethnoses that make up the system at a certain level of passionary tension; k = n + 1, n + 2... n + 21, where n is the initial number of sub-ethnoses in the system. (Not so easy to understand exactly.)

Note: This curve is a generalization of forty individual ethnogenesis curves that we have constructed for various ethnic groups. The dotted line indicates a drop in passionarity below the homeostasis level, coming as a result of ethnic displacement (external aggression).

Part One Kievan Power.

Chapter I The Slavs and their neighbors. - Two Europeans

Let us try to look at the ethnic history of our country from the point of view of what has been said above. In those ages, when the history of our homeland and its peoples began, the human population was extremely uneven. Some peoples lived in the mountains, others in the steppes or deep forests, and still others on the shores of the sea. And all created very special cultures, different from each other, but related to the landscapes that fed them. Understandably, the forest-dwellers could engage in productive hunting, for example, to harvest furs and, by selling them, get all that they lacked. But it could not be done neither by the inhabitants of sultry Egypt, where fur-bearing animals did not exist, nor by the inhabitants of Western Europe, where ermines were so rare that their fur went only for royal robes, nor by the steppe herders.

But the nomads had milk and meat in abundance, and made a delicious and nutritious non-perishable cheese that they could sell. To whom? To the forest dwellers, who made wooden carts for the steppe dwellers to ride on. And most importantly, the inhabitants of the forests made tar, without which the wheels of the steppe carts would not turn. The inhabitants of the Mediterranean coast had excellent fish and olives, and goats grazed on the slopes of the Apennines and Pyrenees. So, each people had its own way of doing things, its own way of sustaining life. So, we must begin our study of the history of peoples by describing the nature and climate of the territories they live in.

The division into geographic areas is often arbitrary and does not always coincide with the division into climatic areas. For example, Europe is divided by an air border corresponding to the isotherm of January, which runs through the Baltics, Western Belorussia and the Ukraine to the Black Sea. East of this boundary the average temperature in January is negative, winters are cold, frosty and often dry, while west of this boundary wet, warm winters prevail, with slush on the ground and fog in the air. The climate in these regions is completely different.

The great scholar, Academician A.A. Shakhmatov, who began a practical study of the Russian annals, studying the history of the Russian language and its dialects, came to the conclusion that the ancient Slavs originated in the upper Vistula, on the banks of the Tisza and on the slopes of the Carpathians.1 These are present-day eastern Hungary and southern Poland. So, our Slavic ancestors appeared and left their trail in history on the borderline of two climatic regions (Western Europe - humid, and Eastern Europe - dry with a continental climate), and this territory is especially interesting to us.

1 There are also other versions of the origin of the Slavs. However, the corrections they make do not change the overall picture of our understanding.

Goths:

During the Great Migration, the Slavs advanced west, north and south to the shores of the Baltic, Adriatic and Aegean Seas. From the west, their neighbors were Germanic tribes. In northeastern Europe, the so-called Balts were in contact with the Slavs: Lithuanians, Latvians, Prussians, and Jatvians. They are very ancient peoples who settled the Baltic territory when the glacier left. They occupied almost all empty areas and spread out quite widely, from about today's Penza to Szczecin. To the northeast lived Finnish tribes. There were many of them: the Suomi, the Esti, and the "white-eyed Chud" (as one of these tribes in Russia was called). Then lived Zyrians, Chud Zavolotsk and many other peoples.

Everything was, as already mentioned, quite stable until the II century A.D., when, as a result of the passionary push the Great Migration of Peoples began. And it started like this. From the coast of southern Sweden, then called Gothia, three Gothic squadrons with their brave men-of-war, the Ostgoths, the Visigoths, and the Gepids departed. They landed at the mouth of the Vistula, ascended to the upper reaches of the Vistula, reached the Pripyat River, passed the Dnieper steppes and reached the Black Sea.

There the Goths, a people accustomed to seafaring, built ships and began raiding Greece, the former Hellas. The Goths captured cities and plundered them and took the inhabitants captive. Greece belonged at that time to the Roman Empire, and the Emperor Decius - a terrible persecutor of Christians, a very good general and a brave man - acted against the Goths, who had already crossed the Danube and invaded Byzantium. The excellent Roman infantry, well trained, armed with short swords that were more comfortable in battle than long swords, faced the Goths, dressed in skins, who were armed with long spears. It would seem that the Goths had no chance of victory, but, to the surprise of contemporaries, the Roman army was completely defeated because the Goths, skillfully maneuvering, drove it into a swamp where the Romans were bogged down to their ankles. The legions lost their maneuverability; the Goths stabbed the Romans with their spears, preventing them from engaging. Emperor Decius himself was also killed. This happened in 251 A.D.

The Goths became masters of the mouth of the Danube (where the Visigoths settled) and modern Transylvania (where the Hepidians settled). To the east, between the Don and the Dniester, the Ostgoths reigned. Their king Hermanaric (4th century), a very bellicose and brave man, had conquered almost all of Eastern Europe: the lands of the Mordva and Mery, the upper reaches of the Volga, almost all of the Dnieper, the steppes up to the Crimea and the Crimea itself.

The mighty state of the Goths perished, as it often happened, because of the treachery of their subjects and the ruler's cruelty. Hermanarich was abandoned by one of the leaders of the Goth tribe of the Dews-Somons. Intolerant of treason, the old king, terrified in his fury, ordered the wild horses to tear apart the chief's wife. "So terrible to kill our sister!" - the brothers of the dead, Cap and Ammius, were indignant. And so one day at a royal reception they approached Hermanarich and, drawing their swords from under their clothes, pierced him. But they did not kill him: the guards had managed to stab them before. But Hermanarich did not recover from his wounds, he was ill all the time and lost his reins. And at that time from the East came the terrible enemy - the Huns.

Huns and “Huns” (eastern and western Huns, very different)

The ancestors of the Huns, the “Huns”, were a small people, formed in the IV century BC in the territory of Mongolia. In the 3rd century B.C. they were experiencing hard times, as the Xianbi nomads pressed on them from the east, and the Sogdians, whom the Chinese called Yuezhi, pressed on them from the west. The attempts of the Xiongnu to take part in Chinese internecine strife were also unsuccessful. The unification of the country, known in Chinese historiography as the "War of the Kingdoms", was then underway in China. One of the seven kingdoms remained, and two-thirds of the population perished.

The Chinese, who did not take prisoners, were not to be messed with. The Xiongnu turned out to be allies of the defeated, and it turned out that the first Xiongnu shanyu (ruler) paid tribute to both eastern and western neighbors, and ceded the southern fertile steppes to China. But here the consequences of the passionary push that forms the ethnicity were telling.

A Xiongnu prince named Mode was not loved by his father. His father, a shanyu, like all Huns and all nomads, who had several wives, was very fond of his younger wife and her son. He decided to send the unloved Mode to the Sogdians, who demanded a hostage from the Huns. Next, the king planned to raid Sogdiana to push the Sogdians to kill his son. But he guessed his father's intentions, and when the shanyu began the raid, the prince killed his guardian and fled. His escape made such an impression on the Xiongnu warriors that they agreed: Mode is worthy of much. The father had to put his unloved son in charge of one of the state's fiefdoms.

Mode set about training the warriors. He began to use a whistling arrow (a hole was made in its tip and it whistled when shot, giving a signal). One day he told the warriors to watch where he shot the arrow and to shoot their bows in the same direction. He did so and suddenly shot an arrow at... his favorite horse. Everyone gasped, "Why kill a beautiful animal?" But those who didn't shoot were beheaded. Then Maudet shot his favorite falcon. Those who did not shoot the harmless bird also had their heads cut off. Then he shot his beloved wife. Those who did not shoot were beheaded. And then, while hunting, he met the shanyu, his father, and he fired an arrow at him. The shanyu turned instantly into the likeness of a hedgehog - the way Mode's warriors pierced him with arrows. No one took the risk of not shooting.

Mode became king in 209. He negotiated peace with the Sogdians, but the eastern nomads, who were called dun-hu, demanded tribute from him. First they wished for the finest horses. "A thousand-legged horse" (li is a Chinese measure of length, roughly equal to 580 m) was the beautifully named fast-footed stallion. Some Huns used to say, "You can't give up a racehorse." "It is not worth fighting over horses,"

Maude did not approve of them, and to those who did not want to give up their horses, he cut off their heads, as was his custom. Then the dun-hoos demanded beautiful women, including the king's wife. To those who said, "How can we give up our wives!" - Mode cut off his head, saying: "Our lives and the existence of the state are worth more than women. Finally, the Dun-hu demanded a piece of barren land that served as the border between them and the Huns. It was a desert in the east of Mongolia, and some thought, "This land is unnecessary, for we do not live on it." But Mode said: "The land is the foundation of the state. Land must not be given away!" And he cut off their heads. Then he ordered his warriors to march on the dun-hu immediately. He defeated them, because the Huns obeyed him unconditionally.

Then Mode went to war with China. It would seem that this war was unnecessary. The nomads lived in the steppe and the Chinese lived to the south, beyond their Great Wall in the humid and warm mossy valley. But the Xiongnu had reason to attack China.

Mode's army surrounded an advance party of Chinese with which Emperor Liu Bang himself was present. The Xiongnu all the time shelled the Chinese detachment with bows, not giving it a break. The Chinese emperor asked for peace. Some of Mode's nobles offered to kill the enemy, but Mode replied, "Fools, why should we kill this Chinese king - they will choose a new one. Let him live. After all, the main forces of the Chinese are in the rearguard; we have not yet fought them." And Mode concluded a treaty of "peace and kinship" (198) with this emperor, the founder of the Han dynasty. This meant that both sides would live without encroaching on each other's lands. The Xiongnu were accustomed to roaming the steppes and were not deterred by the cold. The Chinese liked the mild climate of the Huang He valley and had no intention of going out into the steppe.

At that time, the Chinese had already learned how to make silk, a precious commodity of antiquity. An agreement was reached that the Huns would give the Chinese horses, and the Chinese would pay for the horses in silk. Silk in those days was badly needed by both sedentary peoples and nomads. The people were tormented by parasitic insects, from which only silk clothes were a refuge. And if some hunka received a silk shirt, she no longer had to scratch all the time.

With the help of Sogdian merchants, the Romans also bought Chinese silk. They had the same problem. There was no soap in those days so Romans used to rub their bodies with oil, then scrub them with scrapers together with dirt and afterwards steamed in a hot bath. However, the nasty parasites would reappear after a while.

Roman beauties, seductive and powerful, demanded silk tunics from their husbands and admirers. These tunics were insanely expensive, almost as expensive as gold. The Romans spent vast sums of money on silk, buying it from intermediary merchants in Iran and Syria, giving it to their wives and lovers, and... They had no means to pay their soldiers. Soldiers revolted because of non-payment of wages. Emperors and nobles died in the fire of revolts, but this terrible policy that ruined Rome lasted another two hundred years (I-III centuries).

A very unpleasant situation was also in China. The Chinese received for silk either horses from the steppe people or luxury goods from the Mediterranean. Corals, purple dye, precious jewels went to the nobility, and silk was taken from the peasants. Everyone wanted as much of the precious goods as possible so that they could sell them and to please their wives and daughters. Naturally, the Chinese developed a system in which everything was done, as we would say today, "through blat”. All the wives and concubines of the emperor (and the emperor was entitled to a harem) began to sneak their relatives into the positions of rulers and chiefs. These relatives, getting the right to rule any region, immediately began to clamp down on the peasants to get money for bribes. Their crimes, of course, were a secret from the government: the Chinese wrote denunciations on each other all the time, thanks to the large number of literates among them. The governors were executed from time to time. They have, anticipating their bitter fate, buried treasures in the ground, and let their children know where they came from. So the government, knowing well the habits of its people, began to execute not only the criminal, but also his whole family.

Thus, the silk trade proved disastrous for both Roman and Chinese empires.

Meanwhile, the confrontation between the Xiongnu and China continued. Although China had a population of fifty million and the Xiongnu had about three hundred thousand, the struggle caused by the nomads' need for silk, flour and iron objects was on an equal footing. The horses of the Chinese were much worse than those of the steppe. Expeditions to the Hunnish steppes usually ended in the death of Chinese horse units. When the Chinese learned that Central Asia had "heavenly stallions" - thoroughbred horses similar to those of the Arabian breed - they sent a military expedition there. Having besieged the city of Guishan (in what is now Fergana), the Chinese demanded the best of the stallions. The besieged conceded and the Chinese, coming back with the loot, began to breed a new breed. Having succeeded in that, they began to make successful raids on the Xiongnu. Not only that, they persuaded their nomad neighbors from the east, north and west to oppose the Huns.

In 93, the Xiongnu shanyu lost a decisive battle, fled to the west, and disappeared without a trace. The power of the Xiongnu fell apart. Some tribes dispersed to the South Siberian steppes, others went to China, for at that time in the Great Steppe came drought. The Gobi Desert in the north of China began to expand, and the Huns could move into the dried-up Chinese fields, where they formed sweet-hearted dry steppes. Part of the Xiongnu went to Central Asia and reached Semirechye (the area of modern Alma-Ata). Here and settled the "weak" Huns.

The most desperate moved west. They went through all of Kazakhstan, and in the 50s of the second century came to the banks of the Volga, losing most of their women. Those physically unable to endure such a transition, and of the men survived only the strongest.

The Xiongnu quickly settled in new, comfortable places for cattle breeding, where no one touched them. They acquired women when they raided the Alans, and when they united and intermarried with the Vogul (Mansi) people, the Huns created a new ethnos, the Western Huns, as little like the old Asian Huns as Texas cowboys are like English farmers. These Western Huns (for simplicity we shall call them Huns) went to war with the Goths. (Back to where we left the Goths.)

First, the Huns completed the defeat of the Alans by exhausting their forces with endless warfare. The state of the Huns expanded and occupied the expanse between the Ural (Yaik) and Don rivers. The Goths tried to hold on to the frontier of the Don, but they were exhausted by the grueling battle with the Slavs. So when the Huns came to the rear of the Goths through the Kerch Strait, the Crimea and the Perekop, the Goths fled. The Ostgoths submitted to the Huns, the Visigoths crossed the Danube and ended up in the Roman Empire. The loss of Gothic power gave the Slavs freedom of action. But the memory of the former domination of the southern Russian steppes by the Goths, who once captured the Slavic leader Bozha and crucified 70 Slavic elders, was preserved.

Let us return to those Goths, who took refuge in Byzantium. They professed Christianity according to the Arian rite2, while in the Eastern Roman Empire Nicene orthodoxy prevailed. Union and friendship did not work out. The Romans demanded that the Goths crossing the Danube surrender their weapons, and they agreed. However, when imperial officials began to rob the Goths, demanding bribes from them, taking their wives, children and possessions, it turned out that the Goths retained enough weapons to revolt. In 378 at Adrianople, the rebels fought the Romans, defeated them, killed Emperor Valentus and came to the walls of Constantinople. Although the city was well fortified, the Goths had every chance to take it. However, the Romans were helped by a strange event.

The Roman army had a detachment of mounted Arabs. The horsemen circled around the Goths on foot. One of the Goths fell behind, and an Arab rider overtook him, struck him with his spear, and knocked him down. Then, jumping off his horse, cut his enemy's throat, drank blood, threw his head back and ...howled. The terrified Goths thought it was a werewolf. They retreated from Constantinople and set out to plunder Macedonia and Greece. Even Theodosius the Great could not easily subdue them. But we shall remain ready to settle accounts with the Roman empire and return to Eastern Europe to the Slavs and Ruses3.

The Slavs took part in the Gothic-Hunnian war and were naturally on the side of the Huns. Unfortunately for the Huns and Slavs, the great leader and conqueror Attila fell ill and died in 453. He was left with 70 children and a young widow who had not even lost her innocence. The question of an heir arose: all Attila's sons laid claim to their father's throne, and the conquered tribes supported different princes. Most of the Huns sided with the leader Ellak, but the Hepidians and Ostgoths opposed him. In the battle of Nedao (the Slavic name of the river is Nedava) the Huns were defeated, and Ellak died (454). Attempts by the Huns to fight the Byzantines led to their defeat on the Lower Danube. To the east, in the Volga region, the Huns were defeated (463) and subdued by the Saragurs. Part of the surviving Huns went to the Altai, others went to the Volga, where, mingling with the natives, they formed the Chuvash people. The place of action was left empty.

The birth of the Kiev state

In the sixth and eighth centuries, the Slavs, a strong and vigorous people, had great success. The population multiplied quickly, not so much through monogamous marriages, but through captive concubines. The Slavs spread to the north where they were called Veneads (the word still survives in Estonian). In the south they were called the Sklavins, in the east the Ants. Ukrainian historian M. Yu. Braichevsky established that the Greek word "Ants" means the same as the Slavic "Polyans.

2 Arianism is the teaching of the Alexandrian priest Arius (256-336), according to which God the Son (Christ) is not equal to God the Father. This doctrine was condemned at the Council of Nicea in 325.

3 There are various hypotheses about the origin of the Russians, who in different languages were called differently: Rutens, Dews, Rugs. The author is inclined to see in them a tribe of ancient Germans. The word of the feminine gender "polyanitsa" in the meaning "bogatyrsha" was preserved. But the word "Polyane" in the same meaning is not used today, because the Turkic word "bogatyr" displaced it from use.

By the 6th century, the Slavs occupied Volyn (Volynians) and the southern steppes up to the Black Sea (Tiberians and Ulics). Slavs also occupied the basin of the Pripyat, where Drevlyanis settled, and southern Belorussia, where Dregovichi ("Dryagva" - swamp) settled. In the northern part of Belorussia settled the western Slavs - the Venedi. In addition, already in the 7th or 8th century two other Western Slavic tribes, the Radimichi and Vyatichi, spread south and east to the Sozh, a tributary of the Dnieper, and to the Oka, a tributary of the Volga, settling among the local Ugro-Finnic tribes.

For the Slavs it was a calamity to be in the neighborhood of the ancient Russians, who made it their custom to raid their neighbors. At one time the Russians, defeated by the Goths, fled partly to the east, partly to the south to the lower Danube, from where they came to Austria, where they became dependent on the Herulans of Odoacer (the fate of this branch is of no interest to us). Part of the Russians who left to the east occupied three cities which became strongholds for their further campaigns. These were Kuyaba (Kiev), Arzaniya (Beloozero?) and Stara Russa. The Russes plundered their neighbors, killed their men, and sold captured children and women to merchants-traders.

Slavs settled in small groups in villages; it was difficult for them to defend themselves against Rus', who turned out to be terrible robbers. The prey of Russ was everything valuable. And valuable then were furs, honey, wax and children. The unequal struggle lasted long and ended in favor of Russ, when Rurik came to power.

Rurik biography is not easy. By "profession" he was a Viking, that is a hired warrior. By his origin - Russ. It seems he had ties with the southern Baltic. He supposedly went to Denmark, where he met with the Frankish king Charles the Bald. Then in 862 he returned to Novgorod where he seized power with the help of some Elder Gostomysl. (We are not sure whether "Gostomysl" is a proper name or a common noun for someone who "thinks", i.e. sympathizes with the "visitors" who are newcomers.) Soon a rebellion broke out in Nov-town against Rurik, led by Vadim the Brave. But Rurik killed Vadim and once again subjugated Novgorod and the surrounding areas: Ladoga, Beloozero and Izborsk.

There is a legend about Rurik's two brothers, Sineus and Truvor, which arose from a misunderstanding of the words of the annals: "Rurik, his relatives (sine hus) and his brothers-in-arms (thru voring)". Rurik put his cohorts in Izborsk, he sent his relatives further to Beloozero, and relying on Ladoga, where the Varangian settlement was, he sat down in Novgorod. Thus, by subjugating the surrounding Slavs, Finno-Ugric and Balts, he created his power.

According to the annals, Rurik died in 879, leaving a son, whose name was Igor, which in Scandinavian Ingvar means "the younger one". Since Igor, according to the chronicler, was "detesk velmi" ("very small"), according to the chronicler, power was taken by a voivode named Helgi, that is, Oleg. "Helgi was not even a name, but a title of a Scandinavian chieftain, meaning "sorcerer" and "military leader" at the same time. Oleg and his warriors set out on the great route from the Varangians to the Greeks: from Novgorod southward along the river Lovo, where there was a crossroads, and further along the Dnieper, occupying Smolensk in the process. Varangians Oleg and young Igor came to Kiev. Then there lived Slavs and stood a small Russian team of Askold. Oleg lured Askold and the leader of the Slavs Dir to the bank of the Dnieper and there treacherously killed them. After that Kievers submitted to the new rulers without any resistance. It happened in 882.

Oleg took Pskov and in 883 betrothed the young Igor to the Pskovite Olga. Olga is a female gender of the name Oleg. Here again we are likely to encounter a title without knowing the real name of the historical person. It is likely that Olga, like Igor, was a child at the time of betrothal.

By the ninth century, the split of Slavic unity resulted in the creation of new, previously non-existent peoples. The mingling of Slavs with Illyrians resulted in the emergence of Serbs and Croats, and in Thrace the mingling with nomadic newcomers gave rise to the Bulgarian ethnos. Some Slavic tribes penetrated into Greece and Macedonia, reaching the Peloponnese, which they called Moreia (from the word "sea"). The growing passionarity of the Slavs scattered them all over Europe.

Chapter II Slavs and their enemies.

In the Lower Volga

In the neighborhood of Kievan power in Eastern Europe was born a powerful state - Khazar Khaganate. Its history is worthy of attention. The Khazars themselves were one of the most remarkable nations of that time. Initially their settlements were concentrated in the lower reaches of the Terek River and on the shores of the Caspian Sea. At that time, the water level of the Caspian Sea was -36, in other words, 8 meters lower than today. Therefore, the territory of the Volga delta was very large, reaching the Buzachi peninsula, an extension of Mangyshlak. It was a real Caspian Netherlands, abundant in fish.

The Khazars were a Caucasian tribe that lived in the territory of modern Dagestan. The author of these lines had occasion to find their skeletons in the lower reaches of the Volga; (Gumilev did archeological work in the Caspian), they seemed to belong to teenagers. The skeleton is about 1.6 m long, and the bones themselves are small and fragile. A similar anthropological type was preserved in the Terek Cossacks. Traces of the Khazars' habitation near the Caspian Sea are now hidden by the advancing sea, and only Dagestan grapes, brought by the Khazars from the Caucasus to the Volga delta, remain as evidence of their migration.

The enemies of the Caspian Khazars were steppe Burtasians and Bulgars. Both of them and others were subdued by the Turks in the 6th century. In the dynastic struggle of the victors, some Turks relied on the Bulgars, others on the Khazars. Khazars and their allies won. The steppe Bulgars fled to the Middle Volga, where they founded the city of Great Bulgars. Another part of the Bulgarian horde, led by khan Asparuh left for the Danube, where, mingling with the South Slavic tribes, gave rise to a new people - the Bulgarians. But now we are interested in the Khazars.

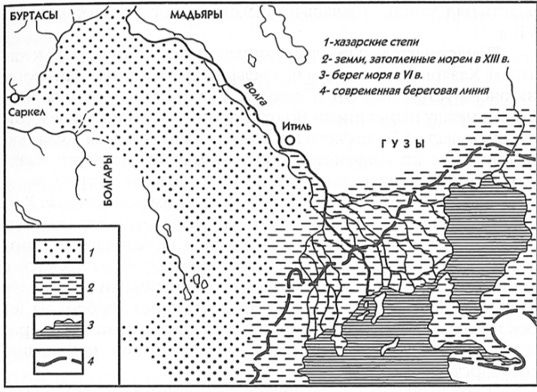

The receding and advancing Caspian shoreline. Fed by the Volga River, Ural River, Kura River, Terek River.

1. Khazar Steppes, (always dry)

2. Lands flooded by the sea in the 13th century

3. Shore of the sea in 6th century.

4. Modern coastline

Volga Khazaria in the VI-XII centuries.

The Khazars had no state power. Now from the language of the tribe survived a word that served as the name of the fortress - Sarkel, which means "white house”. Turkic, Finno-Ugric and Slavic languages do not know anything similar to this name.

In the VII-VIII centuries, the Khazars were subjected to the onslaught of the Arabs advancing through the Caucasus. In this war they were helped by the Turks, a very brave and warlike people. They were the first in Central Asia to master a powerful cavalry weapon - the sabre. And for good reason. The Turks waged frequent wars with China, where the Tang dynasty ruled.

Tang Dynasty (618-907) ruled China with talent and success. Rice under the Tang rulers was cheaper than ever before. The Chinese actively communicated with their "West": the Turks, Sogdians, Tibetans and even Arabs. The Tang dynasty dreamed of a vast Asian empire that would include not only the Central Plains (present-day China), but also the steppes of Mongolia, the forests of Manchuria and the oases of Sogdiana. The Tang struggle for imperial power over Asia began with a victory over the Turks in the mid 7th century.

A representative of the defeated Turkic dynasty fled to the Khazars. The Khazars took him in and... made him their khan. Khan-turk suited them very well. He wandered with this camp in the lower reaches of the Volga, between present-day Volgograd and Astrakhan, in the spring he migrated to Terek, spent the summer between Terek, Kuban and Don, and with the onset of cold weather he returned to the Volga. The Khazars did not have to support their khan. He did not demand taxes from them, being fed by his own nomadic economy. Khan and military nobility who came with him, satisfied with the gifts of their subjects, did not impose a system of extortions and were not engaged in trade. The Turkic khans and beks, leading the Khazars, who by that time had become quite non-military, organized their defense against the Arabs. They were advancing from Azerbaijan through Derbent to Terek and the Volga. The Turks, a people of warriors, defended the Khazars from their enemies and together with them formed a small state in the Caspian region.

This Turkic-Khazar state experienced the introduction of a different people with different traditions and culture.

Aliens from the south

When we study the history of different peoples, we are constantly confronted with a recurring phenomenon of great importance - population migrations. Migrations vary greatly. It happens that a people moves into a foreign territory and adapts to it well. This is how the Slavs spread from the upper Vistula to the shores of the Baltic, Adriatic and Aegean Seas. They succeeded in settling everywhere: they were young, strong and very active. Other peoples, who moved to areas with an unusual climate and natural conditions, disappeared. They either became extinct or mingled with the local population.

This is how the historical destinies of the Van Dal, Sveves, and Goths ended in Southern France, Spain, and North Africa.

There was another form of migration: a group of merchants or a band of conquerors set up a colony in a foreign territory. This is how the English colonized India. They made money there without becoming Hindus, and then returned to England. And the French did not turn into Negroes in their African colonies. After working and serving in Africa, they returned to Paris. For the Khazars, the colonizers were the Persian and Byzantine branches of the Jewish people.

In Iran the Jews appeared in the second century, after the defeat by the Romans in the Jewish wars. The Persians readily accepted the Jews as enemies of Rome and settled them in a number of cities. Thus, Jewish colonies were formed in the cities of Isfahan and Shiraz, as well as in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

But in the fifth century in Persia there were dramatic events for both the Persians and the newcomers. Under Shah Kavad, his vizier Mazdak led a movement that is called Mazdakite after his name. Mazdak was a clever politician and, during another famine in the country, he came up with a simple program to deal with the crisis, as follows. There is good and evil in the world. Good is Reason, and evil is unreason, instinct. It seems unreasonable to have the rich and the poor, when some have harems, and lots of good horses and expensive weapons, and spend their time feasting and hunting, while others go hungry. So, it is right to execute those who have many possessions and to give their wealth and harems to the poor.

Mazdak started this program, but the poor were many and all the wealth of the rich did not go to them. Only Mazdak's supporters, the Mazdakites, got what they wanted. The Persians would have given their lives for their lands, their arms and horses, but they felt sorry for their wives. They expressed their discontent - in return, executions followed. The Shah himself was arrested by the Mazdakites. But he fled to the steppe-Eftalites and returned with their army. His son Khusrov, the energetic Khusraw, mobilized the Sakis from the steppes. All who were dissatisfied with the Mazdakites rose up; many of the children of the executed men. In 529 Khosrov took over and hanged Mazdak and massacred his followers. They were buried alive in the ground vertically and upside down.

You would think, what does this have to do with the Jews? It has everything to do with the Jews. The Jews took an active part in these events. Some were supporters of Shah Khosrow, others were Mazda Whites. After Khosrov's victory, the surviving Mazdakites, Persians and Jews, fled to Azerbaijan. The Jews who had fled settled north of Derbent in the wide plain between the Terek and the Sudak. In the meantime, Jews who had resisted the Mazdakites and had fled Iran during the period of Mazdak's triumph, settled in Byzantium. They were welcomed by the Greeks, albeit with little enthusiasm. Thus, were born the two branches of the Jews already mentioned.

The Jews, who found themselves in the Caucasus, had completely forgotten both their ancient literacy and the traditions and rituals of Judaism. Having forgotten everything, they retained the memory only of the prohibition against working on the Sabbath day. They herded cattle, cultivated the land, and made friends with the Khazars, their northern neighbors. One of the chiefs named Bulan (Türkic for "moose") restored Judaism among his tribesmen. In 730 he took the name Sabriel and invited the Jewish teachers of religious law.

Byzantium, meanwhile, was engaged in a bitter struggle with the Arabs. The Jews, who had found salvation in Byzantium, were supposed to be helping the Byzantines. But they did so in a strange way. In a secret agreement with the Arabs, the Jews would open the gates of the towns at night and let the Arab soldiers in. They slaughtered the men and sold the women and children as slaves. The Jews, buying up the slaves cheaply, resold them for a profit. This could not please the Greeks. But, deciding not to make new enemies, they confined themselves to offering the Jews to leave. Thus, a second group of Jews, the Byzantine Jews, also appeared in the land of the Khazars.

The country north of the Terek liked the settlers. Meadows covered with green grass were beautiful pastures. There were sturgeon and sterlet in the tributaries of the Volga. Trade routes passed through here. The neighboring tribes were not unkind and non-aggressive. Using their literacy, the Jews began to learn and develop occupations uncharacteristic of the local population: diplomacy, commerce and education were in their hands.

At the beginning of the ninth century, the Jewish population of Khazaria added political power to its economic and intellectual power. The wise Obadiah, whose ancient documents say that "he feared God and loved the law," performed a coup d'etat and seized power. He expelled from the country the Turks, who made up the military class of Khazaria. At the same time Obadia relied on groups of mercenaries - Pechenegian and Oguzes. Khazar Turks fought the invaders for a long time, but were defeated and part of them died, part of them retreated to Hungary.

It would seem that there should have been a mixture of Khazars and Jews. But that was not the case. According to the old Jewish wisdom, "no one can detect the mark of a bird in the air, a snake on a rock and a man in a woman," so all the children of Jewish women were considered Jews, regardless of who their father was. The Khazars, like all the Eurasian peoples, determined kinship by father. These different traditions prevented the mixing of the two peoples (ethnic groups), and the difference between the two peoples was reinforced by the fact that Jewish and Khazar children were educated differently. A rabbi teacher would not accept a child to school if he was not Jewish, i.e. if his mother was a Khazar or a Pechenega. And the father taught such a child himself, but of course, worse than what was taught in cheder (school). Thus two different stereotypes (ways) of behavior were established. This difference determined the different destinies of the two peoples: the Jews and the Khazars.

Power and money

The Jews, unlike the Khazars, by the ninth century were actively involved in the system of international trade of the time. The caravans that went from China to the West belonged mainly to the Jews. And trade with China in the eighth and ninth centuries was the most lucrative occupation. The Tang dynasty, eager to replenish the emptying treasury due to the maintenance of a large army, allowed the export of silk. Jewish caravans were going to China for silk. The road went through the steppes of the Uighurs and further across the Semirechye, past Lake Balkhash, to the Aral Sea, to the city of Urgench. The transition across the Ustyurt Plateau was very difficult. Then the caravans crossed the Yaik River and reached the Volga. Here the tired travelers had rest, plentiful food and entertainment. Wonderful Volga fish and fruit, milk and wine, musicians and beauties delighted the caravan drivers. And the Jewish traders running the economy of the Volga accumulated treasures, silk and slaves. Then the caravans would go on to Western Europe: Bavaria, Languedoc, Provence, and across the Pyrenees, ending their long journey at the Muslim sultans of Cordoba and Andalusia.

Not only Jewish but also Sogdian merchants who sent caravans founded settlements in China. One settlement was in the northwestern Chinese city of Chang'an, another in the southeastern city of Canton.

The whole burden of imperial China's economic policy fell on the shoulders of the peasants, because the government officials collected silk from them. The result was a peasant revolt led by Huang Chao (874-901). He took advantage of popular discontent and the fact that the imperial government was weakened by another military setback. The revolt was directed against the encroachment of foreigners. The Tang government was accused of allowing and supporting trade with foreigners. The rebels took Canton, where the entire incoming population was slaughtered. They then marched all the way across the country to Chang'an and even occupied this city with a mixed population. But the townspeople, protecting their wives and children, managed to drive the rebels out. Meanwhile, the Tang government called for help from two tribes: the Tibetans and the Shato Turks. The Chateau chief, One-Eyed Dragon, with four thousand of his horsemen and a similar detachment of Tibetans cut down the two-hundred-thousand rebel army. Huang Chao died, only those who managed to escape escaped: the Shato took no prisoners, (killed everyone). The government won, but China's economy was undermined by the rebellion. Many peasants were killed. There was nothing to export, for there was no one to produce silk or tend mulberry trees. China dropped out of world trade.

The catastrophe that befell the caravan route from China to Spain - the "silk road" - certainly affected Khazaria. But energetic Khazar merchants led by a ruler whose title was "bek", or "malik", found a way out. Their troops moved north.

The Khazar warriors defeated and subjugated the Kama (Volga) Bulgars along the Volga River. Further north stretched the boundless lands, which in the Norse sagas were called Biarmiya, and in the Russian annals - Great Perm. It was here that the traders, the Arahdonites (which means "those who know the way"), organized their trading settlements, trading stations.

Biarmiya forests gave precious furs of sables, martens, ermines. Not only that, but the Rahdonites organized a trade in children. Caravans with furs for the Arab nobility, with slaves and slave women for the harems of the Muslim overlords. The sultans and emirs of the Baghdad Caliphate valued slave warriors ("sakaliba") more highly than independent nomadic mercenaries.

End of Introduction Condensed Fragment.

The text is provided by LLC "LitRes". LitRes has the objective to sell books, and has a large selection in the Russian language from Gumilev. In order to interest people in a purchase, they allow download of fragments for free. This has suited me well, in that I cannot read Russian, and don’t want to bog down translating 100’s (even 1,000’s) of pages.

"[I have also translated this full version of this book, but I have not yet edited it. This shorter version Rus to Rusia is 27 pages. The full book is over 500 pages, but it’s half that amount of text because it is fully illustrated with about 300 medieval woodcuts. Therefore it is a beautiful book, and the reason why I did it. I sincerely doubt that I will post it here though, because adding hundreds of images would be a daunting task.]"

Have you considered having it professionally scanned? I'd be prepared to help with the cost if we can find a method. If the book is rare, this should be done. Perhaps the entire work could be scanned as a PDF file? I can't see the cost being too prohibitive, and as scholars we owe it to posterity to preserve as much as we can of such works.

In that sense I regard our efforts as similar to medieval scribes, who ironically preserved much of Hellenic, Persian and Roman culture, even though their own beliefs stood in opposition. Of course much of the time the scribes had no idea what they were transcribing, it was simply understood that outside the monastic walls knowledge was being lost, and so they sought to preserve what they could and left it to future generations to sort it all out. In that sense, the internet is our Library of Alexandria, and as much as we take out we should strive to put back (while keeping the flames at bay)

Umberto Eco touches on this theme in his 'The Name of the Rose' which was made into a film of the same name starring Sean Connery, in what is arguably the best role of his career.