3: for the "End and the Beginning Again", full version

Flashes of Ethnogenesis, Social and Ethnic Histories in a broad expanse of Eurasia.

So, now that we know what passionarity is, we will show how it is relevant to our main goal - explaining processes of ethnogenesis - and how it relates to social development. The subject of social history, according to the theory of historical materialism, is the progressive development of productive forces and production relations from the Lower Paleolithic to the scientific and technological revolution. It is assumed that it will continue to flow.

Since this is a spontaneous development, it cannot be due to natural forces which do not really influence the change of formations, and stretching a smooth curve from frictional fire to the flight of spacecraft, the line would represent the evolution of mankind. The only thing that remains unclear is, first of all, where did the so-called "backward" peoples come from and why would they not evolve as well?

Secondly, why is there an enormous amount of loss of cultural values in addition to technological and scientific progress?

And thirdly, why did the ethnic groups that created ancient cultures disappear without a trace from the ethnographic map of the world, while those that are now constructing sophisticated machines and creating artificial demand for them emerged only recently?

Apparently, social history reflects the past of humanity one-sidedly, and next to the straight path of evolution there are many zigzags, discrete processes that have created the mosaic that we see on the historical maps of the world.

Because these processes have "beginnings and ends," they have no relation to progress, but are wholly linked to the biosphere, where processes are also discrete.

Thus, social and ethnic histories do not replace each other, but complement our understanding of the processes taking place on the Earth's surface, where "the history of nature and the history of men" are combined.

The curve of ethnogenesis

Therefore, in all historical processes - from microcosm (life of one individual) to macrocosm (development of humanity as a whole) - social and natural forms of movement coexist and interact, sometimes so bizarrely that it may be difficult to grasp the nature of the connection. This is especially true of the mesocosm, where the phenomenon of the developing ethnos, i.e. ethnogenesis, lies, if we understand the latter as the entire process of an ethnos's formation - from the moment of its emergence to its disappearance or transition into a state of homeostasis. But does this mean only that the phenomenon of ethnos is the product of a random combination of biogeographical and social factors? No, ethnos has at its core a clear and uniform pattern. Despite the fact that ethnogenesis takes place in completely different conditions, at different times and in different points of the Earth's surface, nevertheless, by empirical generalizations, an idealized curve of ethnogenesis has been established. Its appearance is somewhat unusual for us: the curve looks neither like a line of progress of productive forces - an exponent, nor like a repeating cycloid of biological development. Apparently, it is best explained as inertial, arising from time to time due to "jolts", which can only be mutations, or rather, micro-mutations, affecting the stereotype of behavior, but not affecting the phenotype.

As a rule, a mutation almost never affects the entire population of its range. Only relatively few individuals mutate, but it may be enough for a new consortium to emerge, which, given favorable circumstances, will grow into an ethnos. The passionarity of the consortium members is a prerequisite for this outgrowth. This mechanism contains the biological meaning of ethnogenesis, but it does not replace or exclude the social meaning.

Changing the level of passionary tension of the super-ethnic system

On the abscissa axis is time in years, where the starting point of the curve corresponds to the moment of the passionary push, which caused the emergence of ethnicity. The ordinate axis shows the passionary stress of the ethnic system in three scales:

Basically this is an energy diagram. The energy is called human passion. It is visible by those who have the urge to DO something, about what they perceive as a current limitation. It is not an average, but a certain percentage is enough to get it all going. Through time these are the stages of the civilization’s growth and decline. At the top the energy (passion) is so intense that people “burn each other out”. That starts the decline.

Try to follow this, or it is not totally necessary. But please don’t get bogged down with Russian words on the diagram. After we pass into examples of (many) civilizations who’s movements illustrate one or more of these phases.

1) in qualitative characteristics from the P-2 level (inability to satisfy lust) to the P6 level (sacrifice). These characteristics should be regarded as a kind of averaged "physiognomy" of the ethnos representative. There are representatives of all the types marked in the figure, but the statistical type corresponding to the given level of passionarial tension dominates at the same time;

2) in the scale - number of subethnoses (ethnos subsystems). The indices are n, n+1, n+3 etc., where n is the number of subethnoses in the ethnos, unaffected by the shock and in homeostasis;

3) in the scale - the frequency of ethnic history events (continuous curve).

The proposed curve is a generalization of the 40 individual ethnogenesis curves that we constructed for various ethnic groups that arose as a result of various shocks. The dotted curve marks the qualitative course of changes in the density of subpassionarians in an ethnos. At the bottom are the names of the phases of ethnogenesis corresponding to the segments on the time scale: rise, accretion, fracture, inertial, obscuration, regeneration, and relict.

As can be seen from the diagram, the abscissa shows the time in years. Naturally, on the ordinate, we put the form of energy that stimulates the processes of ethnogenesis.

But we are faced with another difficulty: we have not yet found a measure by which to determine the value of passianarity. On the basis of the factual material available to us, we can only speak of a rising or falling trend, of a greater or lesser degree of passionariness. However, for our purpose this obstacle is surmountable, for we are looking at processes rather than statistical values. Therefore, we can describe the phenomena of ethnogenesis with a sufficient degree of accuracy, which will serve as the basis for new clarifications in the future.

In any science, the description of a phenomenon precedes its measurement and interpretation; after all, electricity was first discovered as an empirical generalization of a variety of phenomena that looked different from one another, and only later came to such notions as current, resistance, voltage, etc.

Now let us describe the main phases of the process that our curve shows in general terms, and try to show how the process of the gradual expiry of the primary charge of passionarity actually takes place.

We have already said that the starting point of any ethnogenesis is a specific mutation of a small number of individuals in a geographical area. Such a mutation does not affect (or affects insignificantly) the human phenotype; however, it significantly changes the stereotype of human behavior. But this change occurs indirectly: of course, it is not the behavior itself that is affected, but the genotype of the individual. The trait of passivity that appears in the genotype as a result of a mutation causes an increased energy absorption from the external environment in an individual as compared to the normal situation. This excess energy forms a new stereotype of behavior and cements the new systemic integrity.

The question arises: are the moments of mutation (passionary impulse) observed directly in the historical process? Of course, the fact of mutation itself escapes the contemporaries in an overwhelming number of cases or is perceived by them supercritically: as an eccentricity, madness, bad character and the like. Only over a long period of about 150 years segment, it becomes evident when the origin of the tradition began. But even this cannot always be established. But the process of ethnogenesis, or the swelling of the population with passionarity and its transformation into an ethnos, which has already begun, cannot be overlooked. Therefore, we can distinguish the visible beginning of ethnogenesis from the passionary impulse. And, as a rule, the incubation period is about 150 years. Let us take the most obvious examples from the well-known material and move on to consider this question. First of all, let us look closely at when and where the rise of ethnoses took place.

Slavic-Gothic variant.

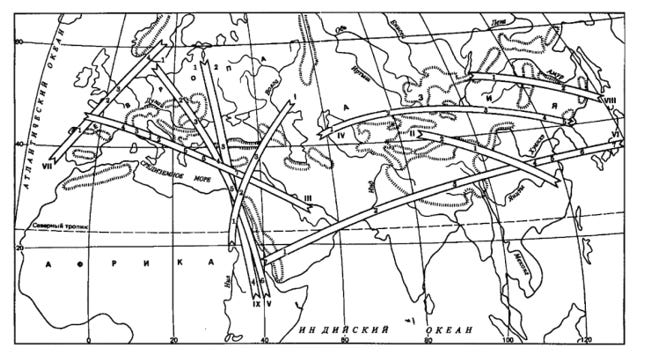

One of them took place at the beginning of our era, in the II century. But where? Only on one strip: approximately from Stockholm, across the mouth of the Vistula, through the Middle and Lower Danube, through Asia Minor, Palestine to Abyssinia (see Fig. on pages 492-493, p. V; not shown). What happened here? In 155 the tribe of the Goths from the island of Skandza was driven to the lower Vistula. The Goths moved rather quickly to the shores of the Black Sea and created a powerful state here, which defeated almost all the Roman cities in the basin of the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea.

Later they were defeated by the Huns, moved west, took Rome, conquered Spain, then all of Italy, and ushered in the Great Migration of Nations. I don't talk about this in detail now, but give the big picture to set the scene.

If we move along this strip, we find that south of the Goths, for the first time in the second century, there are monuments that we attribute to the Slavs. Were there Slavs before that? Yes, evidently, there were some ethnic groups which in this epoch, synchronously with the Goths, created that pre-Slavonic ethnic group, which the Byzantines called "Ants", the Old Russian chroniclers called "Polanes" and which started some kind of ethnic unification, as a result of which the small people living in modern Eastern Hungary spread to the shores of the Baltic Sea, to the Dnieper and up to the Aegean and Mediterranean seas, taking the whole Balkan Peninsula. A colossal spread for a small people!

I was talking about this with Professor V. V. Mavrodin, an expert on these matters, and he asked: "And how can this be explained in terms of demography? How could they have multiplied so quickly, because it happened in only 150 years?" It's very simple. These Proto-Slavs, conquering new territories, obviously did not feel very shy about the defeated women, and they loved children and raised them in the knowledge of their language so that they would make a career in their tribes. After all, this process does not require many men. (each man with 10 concubines.) It is important that there be many defeated women, and the population explosion will be assured. This is apparently what happened.

In the 4th century, as we already know for sure, the Slavs are rivals of the Goths and allies of the Huns and Wolverines. Meanwhile, let us pose the question: what happened farther to the south along this specified strip?

The Dacian tribe rose up against Rome and waged a brutal war. We are now watching the movie "The Dacians. The Romans are at war with the Dacians and it seems natural”. But is it natural? Because the Roman Empire in the time of Trajan included not only Italy, but also present-day Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, France, Spain, Syria and all of North Africa. Imagine such a giant at war with Romania alone, and Romania wins until it is finally crushed. That would seem very strange to us today. But it was strange even then. And yet the fact is that the Dacians at the end of the Ist century, at the turn of the I-II centuries. competed with all this mega, so they had some powerful impetus to counterbalance the numerical superiority of the enemy.

Syrian version of the first century

A similar phenomenon occurred in Palestine, where the ancient Jewish ethnos, already decayed, dispersed, largely exported to Babylon and trapped there and in other Persian cities, lived. There were Jews in Ctesiphon and in Ecbatanes, and they were also in Shiraz. There was a large colony in the west; there were many Jews in Rome. And then all of a sudden, a small ethnic group, made up of Jews who were left behind in Palestine, created a very complex system of relationships within itself (four parties all fighting each other) and was also a powerful rival of the Roman Empire. What changed there?

At this time, a large number of prophets appeared in Syria and Palestine who spoke on behalf of one God or another, or sometimes on their own behalf. Everyone knows Jesus Christ. But then there was Apollonius of Tiana, and Hermes the Thrice-Greatest (Hermes the Tri-Smegist), who supposedly lived in Egypt. There was Philo of Alexandria, a Jew who had studied Greek philosophy and created his system based on variants of Platonism. At this time two major rabbis (Shamai and Gamaliel) completed the Talmud, that is, there was a reform of the ancient Jewish religion.

Religion became the outlet into which passionarity rushed. Where there is a hole, there was a hole in religion, not because people were so religious at the time, but because in the overall administrative oppression of the Roman Empire, it was thought to be harmless.

In the first century, the Romans were in fact godless, having lost faith in their ancient gods - Jupiter, Quirinus, Juno and others. They began to treat them as a relic of their childhood, as sympathetic reminiscences, but no one seriously gave these gods any importance. These gods had already begun to turn into operetta characters, which was completed in the 19th century by J. Offenbach's La Belle Hélène. This process of cultural decay somewhat disoriented the Romans and caused them to miss some important things: the emergence of passionate people who were engaged in a perfectly innocent and licentious activity - making and inventing new cults. The Romans thought it was allowed. Whoever wants can say what he wants, as long as he keeps the law.

Christianity, which to us seems completely monolithic, was not so in the first century. What happened in 33 on Golgotha was known to the world, but everybody had a very different understanding of it: some thought it was just the execution of a man; some said it was the descent of a disembodied spirit who could not suffer and was just pretending to be dead on the cross; others said it could be a man who had the Spirit of God dwelling in him, and so on. There were many currents and the Jews took the lead in this movement!

It was they who with their usual passion raised the fuss about hanging a wretched man - hanging him rightly, but not because of that, because the Romans were scoundrels, because they hanged - who do you think? - pigs! And eat them! After all, the Roman legionaries were given rations in the form of pork and were used to it, so the garrisons that were stationed in Palestine insulted the feelings of the Jews.

What was it like before that? And before that, the Jews had seen the Romans eating pigs, but they were indifferent to it. They said, "Well, why eat such disgusting things and why touch them at all, ugh!" And here they said, "No, not ugh." They said, "Hit it!" And that was already a very significant correction. So, the Judean War began.

The Judean War might have been successful, too, had there not been this very passionary push, as a result of which the Jews (ancient Jews refer to modern Jews the same way the Romans refer to Italians, that is, modern Jewry is another ethnos that has retained to a great extent the cultural traditions of the previous one) divided into four groups which could not tolerate each other.

Those who kept the old law and old customs were called Pharisees. They were merchants, wore long hair, fine combed beards, gold hoops, long robes, studied the Torah, read the Bible, observed all the fasting and rites, and hated the Sadducees, who wore coats, shaved or trimmed their beards in fine style, combed their hair in the Hellenistic style, spoke Greek at home, gave names such as Aristomachus or Diomide, but none of the Jewish names to their children. The Sadducees owned land, money, and commanded troops.

The Pharisees and Sadducees hated each other, but both despised the simple shepherds, the farmers, who used to gather in the caves of the Palestinian mountains near Lebanon, read to each other prophecies and say: "These Pharisees cannot understand what they are saying at all; the Sadducees are hardly ours anymore, but here in the prophecies it is written about a struggle between the spirits of light and the spirits of darkness; when the spirits of light win and the Savior of the World appears, he will save everyone, will drive the Romans out, and will tame these vile Pharisees and Sadducees." And they waited for the coming of the Savior. Christ came to them, but "their own did not recognize him.

There were also sicarii (daggers), or Zealots, that is, the zealous. They were few in number but were very influential because they organized themselves into terrorist groups and killed whoever they wanted to, and they learned how to kill and they mastered the secrets of the conspiracy, so they put fear into everyone.

It took 10 years of empire-wide warfare against one Palestine without support. And when the victory was finally won, the Roman general received a triumph, an honour usually accorded for defeating a very serious opponent.

And where were the Jews before this? It must be said that they posed no danger to their neighbors, at best they waged a small guerrilla war against the Macedonian invaders (in the second century BC), and quite successfully (the Maccabees). No one paid much attention to them. And suddenly! Mutation is always instantaneous.

Byzantine variant

At the same time, there was an even more important event, which should be mentioned specifically: an entirely new ethnos, which manifested itself later under the conventional name of "Byzantines", emerged. The first Christian communities were formed. It can be argued that it was not an ethnos, that it was co-religionists. But what do we call an ethnos? Remember, an ethnos is a collective which differs from other ethnoses in its behavioral patterns and which opposes all others.

Christians, though they consisted of people of all different backgrounds, were firmly opposed to everyone else: we are Christians and everyone else is a non-Christian, a pagan. Pagans is Old Slavonic, and the Greek equivalent is ethnos. So, the Christians distinguished themselves from all the ethnic groups of the Middle East, and thus formed their own independent ethnos. Their stereotype of behavior was diametrically opposed to the generally accepted one.

What did a normal classical Greek of the Roman era, or a Roman, or a Syrian do? How did he spend his day? In the morning he would get up with a headache from last night's drinking (both rich and middle-class people, and even the poor, because they would try to attach themselves to the rich as sycophants, then called "clients"). Early in the morning he would drink a little wine, diluted with water, with something to eat, and take advantage of the morning freshness to go to the market to find out the news (agora is market, and I speak Russian as bazaar). There, of course, he found out all the gossip he needed until it got hot; then he went home, made himself comfortable somewhere in the shade, ate, drank, went to bed, and rested until evening.

In the evening he would get up again, bathe in his tank or, if there were any baths nearby, go there, too, to get the news. He would go out and have a good time, and in Antioch, Alexandria, Tarsus, not to mention Rome, there was a place to have a good time. There were special gardens where they danced the wasp dance, which was an ancient striptease, and you could drink, and after this dance you could have fun for a very inexpensive fee. Then he crawled out on his own, or was brought home completely relaxed and drunk, and he slept it off. And what to do the next day? The same thing. And so, on until he got bored.

Maybe some people enjoyed such a life, but others were bored - how much more could they ask for? And so those who were bored, searched for something to do, so that life would have meaning, purpose and interest, and this was very difficult in the era of the Roman Empire in the second and especially in the third century.

It was too risky to go into politics. What else could it be? Science? Philosophy? - Not everyone was able to do it. Those who were able, they did it, but I must say that in the second and third centuries it was about the same with science: if you did mediocre work, everybody praised you, even gave you all kinds of awards, grants, they said: "Here, try hard, boy, here, well, here copy it, here translate it". But if a man made any discoveries, he was in all the trouble he could get in the ancient world.

And so, it wasn't so easy with science. And besides, the man who did science was generally lonely, because when he studied, he was adored by the teacher, and when he began to say something of himself, the teacher already hated him, and so did the next teacher, that is, he was lonely again. What was he supposed to do? Get a drink and go see a striptease to console himself, that is, to go back to what he had walked away from.

And then it turned out that there were communities where people did not drink, that was forbidden there, where there was no free love, you could only marry or keep celibacy, where people got together and talked. About what? About something he didn't know: the afterlife. My God! Everyone wonders what happens after you die. "You do know! So, tell me!" They knew how to tell, and they also knew how to make their opinions interesting. Nowadays, it's very hard to get anyone excited. It was hard back then, too. But they were so experienced, so talented preachers; the Christians of the first centuries of our era that they carried people away. But such fascinations also brought trouble because the Romans acted according to the law that secret societies were forbidden. Trajan issued a law forbidding all societies, both secret and obvious. Even the firefighters' society was forbidden. And Christians were seen as secret societies. Why? Because they would gather in the evenings, do something, talk, then eat their God - communion, and then go away and do not let strangers into their meetings. So, it was ordered to execute them.

And in those days in the Roman Empire, there were more than enough people willing to denounce their loved ones. Such a flood of denunciations flowed against all Roman citizens and provincials that Trajan, frightened, forbade him to accept denunciations against Christians. "Christians," said the emperor, "should of course be executed, but only on their personal statement. If a man comes and declares that he is a Christian, then he may be put to death, but if he does not say so, and they write on him, throw out all the denunciations, whether anonymous or signed.

To the surprise of Trajan and the Roman procurators, there turned out to be a huge number of people who declared themselves Christians and voluntarily accepted the execution. Later, Trajan's successors stopped even observing this law, because they would have had to execute a lot of very intelligent and necessary people for the state. Church Christians and the Gnostics close to them, as well as the Manichaeans, all fell under this law.

Christians sought death because, through their passionate obsession, they believed so much in the immortality of the soul and the afterlife that they believed that martyrdom was the direct path to heaven. They even demanded death for themselves.

The less powerful passionarians loyally served in the army, the administration, the government, traded, farmed, and because they did not tolerate debauchery and practiced strict monogamy, they multiplied rapidly.

A Christian woman bore a child to her Christian husband every year because it was considered sinful to kill a fetus in the womb, it was tantamount to murder. At that time, the pagans were having fun as they did in the big cities of the world, and had almost no children. By the third century, the number of Christians had grown tremendously, but they retained their integrity.

When the Baguudes rebelled in Gaul against the Roman lathiungials, for example, good armies had to be sent to quell the revolt. The rebellion was not essentially Christian, but some part of these Bagauds or their leaders were Christians. Or maybe they weren't, and it was just rumored about them that they were Christians who were killing their pagan landlords, (which they really did). One of the finest and most disciplined legions of the empire, the Tenth Legion of Thebes, was sent against them to suppress them. They came to Gaul and suddenly learned that they were being sent against their fellow believers. They refused.

Revolts in the Roman army at that time were constant, legions would revolt easily, and a legion had 40,000 men along with the servants. But these didn't revolt. The 40,000 simply refused to obey their superiors, and they knew the penalty for doing so was execution after the tenth - decimation. They put down their spears and swords and said, "We will not fight!" Well, after the tenth man, come out, come out, come out... and they cut off his head. "Will you go to war?" - "We won't!" Once more through the tenth one... and again! The whole legion gave themselves over without resistance. They kept their military oath, they gave their word not to betray, and they kept their word, but not against their conscience. Conscience was above duty to them. There is a church holiday called "The Forty Thousand Martyrs," which commemorates the Tenth Legion of Thebes.

By the 3rd century, Christians swarmed the administrations, military units, courts, bazaars, villages, seaports, and commerce, leaving the pagan world behind. To the pagans only the temples. The Roman worldview, and with it the Roman ethnos, gave way to a new ethnos formed by... out of who? Everybody was there, anybody. It is common for us to say that Christianity is the religion of slaves. That is factually wrong, because a large number of Christians belonged to the upper echelons of Roman society. They were very rich, noble and cultured people.

But then, what is this phenomenon, Christianity? Would you say it was a social protest? In part, yes. But why did this social protest manifest itself only in the eastern part of the Roman Empire, where the order was exactly the same as in the West? It was in Asia Minor, in Egypt, in Syria, in Palestine, much weaker in Greece, and it was not felt at all in Italy, in Spain, or in Gaul. And the orders were the same, and the people were pretty much the same.

It ended up that during another feud, after Diocletian's abdication, his successors, Constantine and Maxentius, fought among themselves. Constantine, feeling that he had fewer troops (he commanded the Gallic legions, while Maxentius stood in Rome), announced that he would ensure that Christians would be tolerant and allowed a cross to be inscribed on his banner instead of the Roman eagle. Many legends are associated with this event, but it is the facts, not the legends, that interest us. Fact is this: Constantine's small army defeated Maxentius' huge army and took Rome. Then, when Constantine's Eastern ally, Licinius, quarreled with him, this small army of Constantine defeated the pagan army of Licinius. Licinius surrendered with the condition that he be spared his life, Constantine of course executed him, but for the cause. Licinius himself killed those who trusted him.

What is the case here? I think there's no need to look for miraculous reasons. The fact is that those Christians who served in the army knew that it was their war, that they were going for their cause, and they fought with redoubled zeal, that is, they fought not only as soldiers, but as supporters of the party they were defending. The idea that seized their minds, pushed them to death, pushed, of course, only the passionates: no idea pushes inert people anywhere.

The idea of defending Paganism did not push anyone anywhere, but there were very talented people who defended Paganism - the philosophers Plotinus, Porphyry, Hypatia, Proclus, Libanius, Jamblich. They were all no less talented than the Gnostics and the church fathers. But unlike their ideas, the new ideas rallied passionate people, became a symbol of passionarity while the former were ignored. Martyrs and fanatics, whose passionarity was "overheated," gathered moderate passionarians around them and won. Constantine, who did not become a Christian, nevertheless allowed his children to be baptized, and the Christians were in charge of the empire.

Amazing, isn't it? Victory was won through death! But if we describe the phenomenon with an open mind, there is nothing else we can say. That's what happened; it's up to us to interpret it. How long did this ethnos, made up of Christian communities, last? A very long time! It emerged as a sub-ethnos in the 2nd century, In Constantinople itself, the inhabitants of the quarter Phanaros, descendants of Byzantines, existed until the 19th century; some islets in the mountains of Greece, in Peloponnese and Asia Minor have survived for some time. That is, the Byzantines went through the entire 1,200-year period of true ethnic history.

In ancient times, Arabia was inhabited by different peoples, who, according to legend, descended from Ishmael, the son of Hagar, Abraham's concubine, who, at the instigation of his wife Sarah, drove Hagar and her son out into the desert in the 18th century BC. Ishmael found water, and if he found water, he gave water to his mother, and he himself was saved, and his people went from him. "The Arabs," although they did not call themselves that yet, for a long time treated their Jewish neighbors very badly, remembering that Sarah's children had taken advantage of their father's entire inheritance, and the children of poor Ishmael had been banished to the desert. And the Arabs lived in that desert from the 18th century B.C. (So, Abraham is dated) to the 7th century A.D. quietly, quietly, without annoying anyone. This was the well-known biblical legend. In fact, it was much more complicated than that.

Arabia is physio-graphically and geographically divided into three parts. First, the coast along the Red Sea is Stony Arabia. There are quite a few springs there, each spring has an oasis, and near the oasis is a city, albeit a small one, but date palms grow - people eat, cattle are driven, there is grass.

The Arabs lived there rather poorly but they had extra work to do because caravans from Byzantium went to India through Arabia Stone and they were hired as caravan drivers or became inn-keepers in caravanserais, selling their wares. Dates and fresh water were sold to the caravaners at high prices. They paid because they had nowhere else to go. The Arabs compensated the poverty of their natural conditions by raising the price of goods, and everything went quite well. They lived and made money.

Most of Arabia is desert, but not desert in our sense. When real Arabs saw our Central Asian desert, they marveled and said they couldn't even imagine such a desert. The Desert is such a land, where there is not a continuous cover of grass, but bush to bush, separated by dry land, i.e. as we would say, dry steppe. Besides, there is the sea on three sides, so it rains and the air is rather humid. Camels could be chased as much as you like, and not only camels (but they mostly rode camels and donkeys). They had nowhere to hurry, and they lived there very peacefully. They did have wars, but they were extremely humane.

For example, one war between two tribes happened because of a cameless who stepped on a quail's nest and crushed its chicks. An Arab, the owner of the land where the nest was, avenged the nestlings and wounded the camel with an arrow in the udder; the owner of the camel killed him with a knife in the back. The tribe did not give up the murderer and the relatives of the murdered man started a war. This war went on for thirty or forty years, and in all that time there were two or three of them killed. That's how quietly they lived.

But they had an original culture, a lot of poetry. In Russian poetry we have, for example, five different sizes - iambus, chorus, anapestus, amphibrachium and dactyl. The Arabs have 27, because the camel moves at different gaits, and to get used to the rocking, you have to recite poems to yourself in time with the rocking, so 27 different sizes. Imagine an Arab riding through the desert and composing a poem, then immediately singing it. A useful occupation for a nomad. Of course, their poetry was not for recording or memorizing, it was suitable only for the occasion.

Finally, in the very south of Arabia, there was Happy Arabia-Yemen. It was almost a tropical garden, and had mocha coffee which was transported to Brazil where it took root but got worse. The real, best coffee in the world is in Yemen, and the Arabs drank it with great pleasure. They lived in this tropical garden, prospered and would have wanted nothing if they had no neighbors. Alas, they had neighbors. On the one side the Abyssinians who were always trying to conquer them; and on the other side the Persians who drove the Abyssinians from Arabia back to Africa. The war was terribly bloody, no prisoners were taken, and it was not the Arabs who fought, but the Abyssinians and the Persians. The Arabs themselves tried to live peacefully, only occasionally robbing individual travelers or each other. But the latter was rare, because they had a custom of family mutual assistance: if a man was robbed, then his whole clan would stand up for him, and the robber would be in trouble. They were afraid. But strangers could.

Sometimes they were enlisted in the armies of the Persian shahs or Byzantine emperors, and they were taken, but not paid much, because they were not enough combat worthy. They were used as irregular troops for certain maneuvers, like throwing them behind enemy lines or for reconnaissance; they were not put in combat lines because they were very unstable and cowardly. They ran away! But why should they really have to die for somebody else's cause, what for? To make money, yes, but to get killed for it - who needs it? The reasoning seems to make sense.

But in the second half of the 6th century, the Arabs suddenly had a pleiad of poets. I must say that, from my observations, poetry is very difficult to write, and the fee that poets are paid for good poetry doesn't pay for their work at all. And yet they write, even without royalties, because they have a propeller inside them, and it makes them write poetry to express themselves. What is that propeller? That's what we have to find out!

They want to express themselves and their feelings, they want to gain the utmost respect and admiration for it, that's how "the passion" guides their actions. Feeling, not reason.

By the seventh century, there were more and more poets, and they began to write good poems, mostly Pagan. Poems about love, guilt, and sometimes about a conflict. There was no sense of purpose because the Arabs had no single ideology. The Bedouins, who lived in the desert, thought that the gods were stars; there were as many stars in the sky, so many gods, and everyone could pray to his own star. There were many Christians, many Jews, there were fire-worshippers; there were all sorts of Christians among the Arabs - Nestorians, Monophysites, Orthodox, Armenian-Jacobites, and Sabellians. But since all were engaged in their daily affairs, there were no religious clashes, and they lived peacefully.

And then, in the early seventh century, a man named Muhammad appeared. He was a poor man, an epileptic, very able, but uneducated, completely illiterate. He used to drive a caravan, then he married a rich widow, Khadija. She provided him with money, which enabled him to become a fairly respectable member of society.

And suddenly he said that he was called to correct the vices of the world, that there had been many prophets before him - Adam, Noah, David, Solomon, Jesus Christ with Mariam, that is, the Virgin Mary - and they all spoke correctly, but people mixed up everything, forgot everything, so now he, Muhammad, will explain everything to everyone. And he explained everything very simply: "There is no God but God," and that was all. And then they began to add that Muhammad is his prophet, that is, God is Allah, which means "the only one," and he speaks to the Arabs through Muhammad. And Muhammad began to preach this religion.

Six people accepted his teachings, and the rest of the Meccans said, "Give it up, give it up, we'd better go and listen to some funny stories about Persian warriors. "Come on, I have no time," the merchants said to him, "I have counting to do, I have a balance to settle, the caravan has come. - "Never mind," said the Bedouins, "there's a camel gone, I have to bring it to pasture.

That is, most of the Arabs were least willing to talk to him, but there was a bunch, first six people and then several dozen, who sincerely believed him, and, most importantly, among them were strong-willed, strong people, both from rich and poor families.

These were: the terrible, cruel, adamant Abu Bekr; the just, unbending Omar; the kind, sincere, in love with the Prophet Osman; the son-in-law of the Prophet, a heroic fighter, the sacrificial man Ali, who married Mohammed's daughter Fatma, and others. And Muhammad kept preaching, and the Meccans were terribly fed up with it. After all, he preaches that there is only one God and everyone should believe in him, but what to do with people who come to trade and believe in other gods? It's uncomfortable at all, and boring, and pushy. So, they said to him, "Pre-rush your outrage."

But Muhammad had an uncle who warned the Meccans not to touch Muhammad under any circumstances. "Of course," my uncle agreed, "he's talking nonsense, and everyone is sick of it, but he's still my nephew, I can't leave him without help. Kinship was still valued in Arabia at the time. But his uncle advised Muhammad, "Run away!" So, Muhammad fled from Mecca, where they decided to kill him so that he would not disturb people's lives, to Medina (then called Yathrib, but after Muhammad settled there, it was called Medina-tun-Nabi, "the city of the prophet," while Medina means simply "the city").

Unlike Mecca, where rather rich and well-to-do Arabs lived, Yathrib was a place where all kinds of peoples settled, forming their own quarters: three quarters were Jewish, there was a Persian quarter, there was an Abyssinian quarter, there was a Negro quarter, and they all had no relationship with each other, sometimes quarreling, but there were no wars yet. And when Muhammad and his faithful, who followed him, showed up, the inhabitants said to him, "Here, live here alone, apart from everybody else, nothing, you're not in the way."

But then the unexpected happened. Mohammedans, or as they began to call themselves, Muslims, the champions of the faith of Islam, immediately launched the most active campaign. They announced that a Muslim could not be a slave, which meant that anyone who uttered the formula of Islam, "La Illa il Alla, Muhammad rasul Alla" ("There is no god but Allaah, and Muhammad is his prophet"), was immediately free. He was accepted into the community. Some Negroes went over to them, some Bedouins. And all who embraced Islam believed in the cause. They lit up with the same fervor that Muhammad and his closest associates had. So, they quickly established a community that was large and, most importantly, active. The Muhajirs, who came from Mecca, who were few in number, were joined by the Ansars. The Ansars are literally "adherents": the inhabitants of Medina.

Muhammad was the head of one of the strongest communities in the city of Medina itself. Here he gradually began to bring his own order. First, he dealt with the pagans who believed in the stars. "No," he said, "there are not a mass of gods in heaven, but one Allah, and whoever does not want to believe me should simply be killed, because he insults the majesty of Allah. And they killed them.

Then he confronted the Christians and told them that he was correcting the law that Jesus Christ himself had given. The Christians said, "Give it up, where are you to correct anyone, you illiterate man? They were killed or forced to convert to Islam. Then he came to the Jews and told them he was the Messiah. They quickly took the Talmud, the Torah, looked at the books and said, "No, you don't have such and such and such attributes, and you are no Messiah at all, but an impostor." "А!" - he said. And two blocks, one after the other, were slaughtered to the last man. The Jews from the third fled to Syria.

Finding himself the strongest in Medina, he decided to conquer Mecca. But Mecca was strong, and the Muslim army was overturned. Then Muhammad took a detour - he subdued the Bedouins and forced them to recognize Islam. The Bedouins who had nowhere to flee to - the steppe was like a table all around, where could they go? And they could not get away from their camels - they said: "Let them! All right," and continued to pray to the stars, but they officially recognized the faith of Islam and gave people to Mohammed's army. Why? It was worth going to Mecca: Mecca is rich, you can plunder.

Muhammad seized Hadramawt, which is the southern coast of Arabia, and there were many castles there, and he demanded that they recognize Islam. They thought and thought and thought - what's there in the end, I will say one phrase, what will it do for me? Recognized and people were given. Then he went again to Mecca.

And the Meccans were clever and very cunning people, they said: "Look, Mohammed, why are you going to conquer your native city, we will defend ourselves, somebody will be killed, well, who needs it, let's make up, eh? (Arabs are a very practical people.) Recognize a couple more gods, so that there are three: Lata - a very good god and Zuhra - "beauty" (the planet Venus). Well, what difference does it make to you whether there is one or three, and we will honor them all." And Muhammad was about to agree, but then Omar and Abu Bakr cut him off: "No, Allah is one. So, Muhammad gave out another surah, that is, a prophecy that Allah is one and there are no other gods, the others are just angels of God.

The Meccans had to agree: "All right, let there be angels, but what we will not cede to you is the black stone; people come from everywhere to worship it, and they all buy food from us in the bazaar. No, we won't give you the black stone. After all, the black stone fell from heaven, so it is from Allah. Then Muhammad agreed, and all Muslims also agreed, acknowledging that the black stone was from Allah. And after that Muhammad occupied Mecca; his worst enemies were among his subjects and sent their armies to him.

Let us turn to the psychology of the Arabs. Muhammad did not pursue any personal goals; he took deadly risks for the sake of a principle he had created for himself. In essence, in terms of theology, Islam contains nothing new in itself in comparison with those religions and currents that at that time already existed in the Middle East. Thus, as far as theology was concerned, it was not worth a damn, and the Arabs were right not to argue about it; they gave up their customary cults, said the formula of Islam, and went on with their lives.

Was that the point? That was not the point. The group that had formed around Muhammad was made up of fanatics just like him. Muhammad was simply more creatively gifted than Abu Bakr or Omar. He was simply more emotional than even the good Othman. He was even more selflessly devoted to his cause than the desperately brave Ali, and yet he didn't personally benefit from it.

Muhammad declared that a Muslim could not have more than four wives; it was sinful. And the Arabs were very fond of sinning at that time. Four wives was the minimum in those days. I don't want to be obtrusive, but let each man think about it, did he change his girl friends four times? He probably did. And back then, in those days, every girlfriend was considered a wife, so you had to get a divorce. It was a very unprofitable business, because marriage was civil and divorce was civil, like ours, and it was connected with the division of property. The wives preferred to stay with the old husband when he took a new wife, it was more profitable for them. And so, the fact that he himself had only four wives - it was in general self-restraint.

He also did other things that were very important to the Arabs. He himself was epileptic and therefore could not drink wine, for it was very bad for him. So, Muhammad declared that the first drop of wine ruined a man, and forbade him to drink wine. And the Arabs loved to drink, they loved to drink terribly. So, this prohibition greatly hindered the spread of Islam.

When the Arabs became Muslims, they didn't change. They sat in a closed courtyard in a small company, invited no strangers, put a big jar of wine, dipped their fingers in it and, since the first drop of wine kills a man, they shook it off - and the prophet didn't say anything about the rest. They could always find a way out.

But something very important happened. Around Muhammad and his group, like water vapors around a speck of dust, people began to gather in a clump. There was a community of people united not by their habitual way of life, not by their material interests, but by the consciousness of the unity of destiny, the unity of the cause to which they had given their lives. This is what I call a consortium, from the Latin "sors" for "destiny". The people included in the consortium are people of one destiny.

The explosion of ethnogenesis that brought to life the Muslim world and its religion, Islam, took place in the latitudinal direction (see Fig. 492-493, p. VI) and, in addition to Arabia, captured India, China, Korea, and Japan. We shall not talk about the last two, confining our attention to Eurasia.

So, what happened in the 6th century to these countries?

We have already spoken about the beginning of the Arabian ethnogenesis and the formation of the primary consortium of the Mohammedan followers before, and in some detail. Now let us consider this subject in the aspect which interests us now.

After Muhammad reached a compromise with the Meccans, they recognized the faith of Islam that he preached. Just before his death, he wrote two letters-one to the Byzantine emperor, the other to the Shah of Persia-demanding acceptance of the faith of Islam. The Byzantine emperor left the letter unanswered: what is there to talk about with this savage. And the Shah of Persia wrote a very snide reply. Then Mohammed decided that we must wage a holy war and force everyone to accept Islam. And after that, he soon died.

Immediately, Arabia broke away from most of Islam and ceased to obey the Muslim community and the Caliph, that is, Muhammad's vicar, Abu Bakr. For two years the whole of Arabia had to be subjugated in a most savage war. The slaughter was appalling. Survivors were forced to convert to Islam. The least resistance was shown by the Meccans, who decided that all the same, "we will say that we accept it, but it is impossible to verify, and he will leave us alone". So that's what happened. And they supported the Muslim community: the Bedouins were subdued, Yemen was conquered. And after Abu Bakr's death, in 634, caliph Omar undertook a campaign against Byzantium and Persia, two of the greatest powers of that time.

Byzantium had a population of about twenty million. Persia was smaller, but still had borders reaching into present-day Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. That is, two great countries with regular armies paid no attention to these Arabs, who were useless and fearless, and didn't even have horses. They marched on donkeys and camels, and before the battle they dismounted and fought.

At Yarmouk in Syria and at Kadisia in Mesopotamia in 636 first the Byzantine and then the Persian armies suffered a crushing defeat. The Arabs occupied Syria, invaded Persia, then seized Egypt from Byzantium almost without resistance. Then reached and occupied Carthage, marched along the coast to the Straits of Gibraltar, crossed into Spain, crossed the Pyrenees, and were stopped at the Loire and the Rhone in 711. So great was the passionate rise of the Arabs.

It was exactly the same in Persia. After the battle of Nehavenda (in Midia) in 648, when already the Persian militia, not the regular army, was defeated, the last Shah Yezdigerd III fled. The Arabs took over the whole of Persia, subjugated it, and forbade fire worship. The fire-worshipping Intellectuals went to India and still live there. The rest of the Persians converted to Islam. The former Sassanid aristocrats, descendants of the Persian reigning dynasty, in the Arab period became synonymous with the beggar who walks the great roads and begs for mercy.

From Persia, the Arabs attacked the rich country of Sogdiana, our Central Asia. Such Sogdian cities as Bukhara, Tashkent, Samarkand, Kokand, Gurganj were surrounded by strong walls and had a large population. Beautiful oases fed the population of these cities. The warriors there were very brave men - dekhkans; they wore belts of golden needlework and splendid swords; they had good horses. And the Arabs came there in small clumps, with their small forces, and seized city after city, taking it sometimes by deception, but mostly by force. The Sogdians began to surrender.

The question is, why does a rich strong country become the victim of a pauper conqueror? Obviously, the invaders had some additional impetus. Now we know it - it's passionarity.

They coped with the oases in Central Asia fairly quickly, but as soon as they entered the steppe, they encountered nomadic Türks and Turgesh (Turgesh is one of the varieties of the Western Turks). And that is where their advancement stopped. Though Arabs offered the Turks to accept the Islam, but the Turks answered with pride. The Turgesh Khan Sulu said: "All my people are warriors, but what do you have? Craftsmen, shoemakers, merchants. We can't do that, so your faith doesn't suit us either".

The outbreak of ethnogenesis of Muslim Arabs in the 7th-9th centuries.

It should be said, that the nomadic population north of Tashkent and Chimkent, in the Tien Shan mountains, in South Kazakhstan was extremely rare. The Tien Shan mountains were inhabited by the Turgesh, Yagma and Chigili, three tribes. And in the steppes lived ancestors of Pechenegs called Kangar, and the country itself was called Kangyu. The ancestors of the Turkmen, the descendants of the Parthians, lived as far as the Syr Darya. This sparse population was quite enough to stop the Arab onslaught.

Nevertheless, the surrendered population of Sogdiana, after a very long war, the peripeteia of which I shall skip the details, were obliged either to pay a huge tax, or accept Islam. Then the Arab Caliph in Damascus said, "No, the fact that you converted to Islam is good, it will save your life after death, it will give you paradise, but you still have to pay money. Then they started a terrible uprising. The uprisings were accompanied by the most brutal executions.

At this time the Tang aggression reached its climax. Chinese troops marched into the valley Talas and faced Arab armies in 751. Here was the Battle of Talas, where three days fought regular Chinese troops, commanded by a Korean Gao Xiang Zhi, a brave man, a huge growth, broad-shouldered, and against him the Arab troops, augmented Persian volunteers from Khorasan, which is also a regular army; they commanded Ziyad ibn Salih. They fought for three days without being able to win. It was the Altai tribe of Karluks who decided to strike at the Chinese. They decided that the Chinese were worse than the Arabs. They didn't say the Arabs were better than the Chinese, no. It was not a question of who was better, but who was worse. The Chinese were worse, after all. After that, the Chinese army fled and no longer tried to penetrate into Central Asia.

Ziyad ibn Salih was executed for his part in the conspiracy about six months after his grand victory. This was because about a year before this battle, the Arabs had had a coup because Muhammad's principle of organizing the country along denominational lines ignored ethnic lines. Anyone who uttered the formula of Islam and agreed to be circumcised could become a Muslim. He was then enlisted as a potential force in the Caliph's armies, enrolled there and could serve or not serve as he was able, but many preferred to fight and bring home the spoils. And the spoils were enormous. For example, the Persian carpet of the Shah's palace had to be cut into pieces because the Arabs did not have a palace where it could be spread. They brought women in great numbers, and immediately they were sold in the bazaars, and cheaply, because there were many women prisoners. They were bought for the harems. True, an exception was made for aristocrats. For example, the daughter of the Persian shah Yezdigerd was sold according to her wishes: to whom she wished to be sold. And before her went the buyers - Muhammad's closest associates: Caliph Omar - she said: "No, he is very cruel"; Osman - "No, he is very weak"; Ali - "Very fat," she said, "not suitable"; his son Hasan, a young man, nephew of the Prophet, son of Fatima - she looked and said, "He has bad lips, he is voluptuous, he will love not only me, but also other women". When Huseyin passed, she said: "Sell me to him, I agree. Immediately the deal was formalized. Slavery in the Arabs at that time took such forms, which nowadays seem exotic.

In general, I must say, this approach was very reasonable. In the Persian house-building of the 11th century. - The Kabusname, adopted by the Arabs, stated that a slave could be bought only with his consent, and if he quarreled with his master for some reason and wished to be sold, it was best to take him immediately to the bazaar and sell him. Otherwise, you might get into so much trouble with him that he is not worth it. It was more like an employment transaction, but it was done as a sale-purchase.

And so, these slaves, slave girls, prisoners, converts, all who became Muslims, all who served in the Muslim armies, turned out to be a huge mass of people, connected with each other only by administrative and political ties. But their ethnic essence didn't disappear. Therefore, when the power weakened and the faithful caliphs, the heirs of Muhammad, lost the war with the hypocritical Muslims - the descendants of his enemies - and they seized power, the hypocritical Umayyads established the caliphate of Damascus.

There, virtually everything was allowed. It was officially considered that the faith of Islam prevailed, and it was forbidden to drink wine in public places. Christians and Jews could drink, but Muslims could not. Let them pray! But Muslims drank wine at home, and here no one was watching and no one found out what they were doing. Besides, they also had to pray five times and perform ablutions. When they were watched, they did all these things, but as soon as they stopped watching, they ignored all the rules and it was looked at through their fingers.

The unity of the Muslim community disappeared; the community disintegrated into sub-ethnos. And it became clear that there were Medinan Arabs, Meccan Arabs, Qalbis (southern) Arabs, Qaisites (northern) Arabs. And they all fought among themselves and started a terrible massacre. If I were to talk about the Arabs specifically, I would have to list their foreign wars and their internal wars, uprisings and their suppressions. So, there you go! Their numbers are the same. The Arabs spent about half their stock of passionate energy, their fighting ability, on suppressing their own tribesmen, because their internal wars were even more brutal than the Christians in the West, and the pagans in the East. It went so far that Mecca was stormed by the troops of the caliph of Damascus (Umayyad) with flamethrowing weapons, burned the temple of the Kaaba. Even the stone cracked from the heat. But they did not care about these little things; they were solving their political problems. And here is where the ethnic principle came out with all its force.

The Persians conspired with the Kelbite Arabs against the Qaysites, supported them and overthrew the Umayyad dynasty, which was replaced by a new dynasty, that of the Abbasids, distant relatives of the Prophet, who had no right to the throne. It suited the victors, however. The Abbasids were all mixed up to an extent that we cannot even imagine. And it was not a matter of genetic mixing. If, for example, your grandmother is Spanish, you either don't know it, or you sometimes remember it just for fun. But if your mother is Spanish, she will teach you, first of all, to speak Spanish, she will sing you Spanish songs from the cradle, then she will teach you that you must defend your honor with a sword in your hand, that you must be jealous, drink chocolate and do a lot of other things.

But if you have a Finnish mother, for instance, she will tell you that it is all trifle and garbage, and that after a time the son of a Finnish woman from the same father as a Spaniard will drink plenty of vodka and will not be jealous, and will not learn to fight with sword, and if he must, he will take a club and beat his Spanish brother, who will fight with a sword, with a club, etc. Now, unfortunately, we do not know the genealogy of all the figures of the Abbasid caliphate, but we do know the caliphs. One had a Persian mother, the second a Berber, the third a Georgian, and so on. It was a terrible mishmash of people with different stereotypes of behavior and upbringing. The Abbasid caliphate was held together more or less by the weakness of its opponents. But it began to fall apart from within.

Spain was the first to fall, where a member of the Umayyad dynasty, Abdarrahman, fled, and although a government official was sent there as a viceroy, he was forming a party to propose to separate from the Caliphate and live on his own. So, they did. Then Morocco, inhabited by the Kabylian Moors, broke away. Then Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Central Asia, Khorasan, Seistan - the eastern part of Persia. The Caliphate collapsed.

Why are the details important? Because the influence of Muslims and Muslim aggression on the people of our country was enormous. Central Asia, which was ruled by Arab officials, the emirs (the emir is literally "special commissioner"), became a Muslim country. When the Arabs were replaced by local rulers with the title "sultan" (also an Arabic word), they were already Muslims. From the terrible massacres inflicted on people during their conquest (and the Arabs killed with gentlemanly care: only men; women were sold into harems, from which they became full wives), a mixed population emerged, called with the same word as their conquerors, the "Arabs. The Arabs had few terms of their own and borrowed words from others, notably Persian. In Persian, "crown" is "taj," and "crown troops" is "tajik. So, the descendants of Arabs and Sogdian women became known as Tajiks, who still exist today (this is an example of ethnogenesis). They were formed in the eighth century and have not lost their ethnic face, nor their brilliant abilities, nor their stereotype of behavior, which they acquired then as a result of mixing the Arabs with the Turks.

The Indian (Rajput) variant

And now let's direct the caravan of our attention through the burning deserts of Baluchistan to the Indus River that irrigates the surrounding dry steppes, where the famous Rajput revolution took place in the 8th century. It transformed the Buddhist monarchy of the Gupta Empire's successors into a fragmented Rajput India bound only by the caste system. The Indus Valley is an area very similar to our Turkmenistan in terms of climate and landscape. Sands, hills with sparse grass, a large river flows, like our Amu Darya. A lot of islands and sandbanks on the river, so even during the British rule, the Indians preferred to cross the Indus not by boat, which went from one bank to another and round all the islands, but by whitewater. It is true that there are crocodiles in the Indus, but the Indians were used to them. They took a long stick with them, and when a crocodile wanted to attack a swimmer, the Hindu would hit him in the nostrils with the stick, and the crocodile would immediately disappear. In general, the Indus and the surrounding desert are like a landscape continuation of Central Asia, which is why many Central Asian tribes, leaving their homeland, settled in the Indus Valley. By the time of the shock there were three of them: Kushans, Saks, and Ephthalites: all three were different ethnic groups. But when they arrived on the new territory, they forgot about their origins and mingled with the natives, and it was very difficult to distinguish them from the locals. But it was still possible to distinguish them by their cults: the Central Asians worshipped the sun as their deity, the Hindus the serpent, but there was no dispute between them over it.

And in central India and in Bengal there was a cultural and powerful empire of the Gupta dynasty, which worshipped the sun - Aditya - and Buddhism. Buddhists were very much in high esteem in the Gupta empire, as in all despotic empires. The despotic regimes benefited from symbiosis with Buddhists. The rulers ripped off their peasants and their tax population with terrible force in order to maintain the opulence of their court and the power of their hired troops, because the Buddhists preached that the world is an illusion, and because you are robbed of illusory money or illusory bread or forced to work to build an illusory road, it all only seems that way to you. You obey, it's more peaceful. Of course, the Hindus obeyed, what can you do? Since there is no passionarity, you will obey.

But the passionary tremor, which took hold of Indus valley, affected Hindus like on Arabs, in the sense of their consolidation, though their religious conception was completely different. They remembered that once there had been an ancient Hindu religion, which they had forgotten to think about, because now only learned Brahmins knew it, who read in Sanskrit, which is an artificial language, like our Church Slavonic; ordinary Hindus could not read in it. But they really needed some wisdom to express their new anti-Buddhist sentiment, their new ethno-cultural dominance. And there was a brahmin, Kumārīla Bhatā. A very venerable man who loudly declared that Buddhists talk nonsense, claiming that the world is an illusion. He seemed to be saying what my father was saying:

There is God, there is the world, they live forever, And, men's lives are momentary and miserable, but all is contained in man, Who loves the world and believes in God.

The conclusion of this concept was very simple: beat the Buddhists and destroy the Gupta empire! This was made easier by the fact that the legitimate dynasty had ceased, the usurpers were in power, first Harsha Vardana, then Tirabhukti, a rare rogue, who had brought down the authority of the ruler.

The empire, therefore, collapsed rather quickly under the onslaught of the Rajput supporters of Kumarilla. The Rajputs tore it apart with their sabers, with Kumarilla and other Brahmins like him ordering the murder of all Buddhist monks. And since a Buddhist in India is necessarily a monk, it was very easy to distinguish them, and they were quickly put to death. But there were sections of the population that supported the Gupta regime and Buddhism accordingly. And then the caste system was restructured. Those who had helped the Rajputs in their Rajput revolution were placed in higher castes, different from the old varnas, of which there were only four. The new castes became numerous. Brahmin supporters were placed in the higher castes, neutrals in the middle castes, and those who protested were placed in the lower castes, the "touched" but the lowest. But there were also the "untouchables," who were the worst off because, for example, they were forbidden even to drink water from springs and rivers, allowed only from animal tracks or to lick dew from leaves. They dared not touch anyone and did the dirtiest and lowest paid jobs, and some groups of untouchables were simply to be exterminated. So those who would not risk remaining in their homeland fled from India and appeared first in Central Asia, then in the Middle East, then in Europe and Russia. They still wander to this day and are called Gypsies.

The Rajputs did not create a single state. They were extremely independent people who did not want to obey anyone. So, they created a mass of small principalities, feuding with each other, but held together by a single caste system, that is, a single stereotype of behavior and a new and unified Brahminical religion, which, however, split into two confessions, which argued with each other, but did not fight each other: Shivaism and Vishnuism.

At the head of the new Indian religion, shaped by one of Kumarilla's followers, Shankara, was the Hindu trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Creator Brahma sleeps all the time, but from time to time he wakes up, creates the world and goes back to sleep; while he sleeps, the world deteriorates, then Brahma wakes up again, sees the mess, creates the world again and goes back to sleep until the next reconstruction. And in the world, itself there are two beginnings: the guarding beginning - Vishnu - and the destroying and recreating beginning - Shiva. The priests of Vishnu were called guru-teachers; they taught to abstain from all kinds of intoxicating drinks, which destroy the body, and were obliged to pay attention to all the women of the Vishnuite cult.

If, say, an old man-teacher comes to a village, he has to sleep with all the women here, otherwise it is a terrible offence; it means that he has neglected some family with his boons, and he has to pay attention to all the faithful; he may not feel like it, but he must, maybe there is some old woman or ugly woman, it does not matter - do your duty!

Shivaites, on the contrary, were strictly forbidden to come into contact with the female sex, and narcotic and intoxicating drinks were imposed on them in order to destroy their flesh as quickly as possible, to exhaust it and thus prepare it for restoration anew. That is, here and there nothing in common with Buddhism, only the idea of the transmigration of souls remained, because it was at the heart of all Eastern wisdom.

Sometimes the Vishnuites and the Shivaites argued, but these disputes, as we would say, were not antagonistic; they were more like the struggle of the Democratic and Republican parties in America: one complements the other. There was little order in India at this time, because South India was struggling to submit to the new Rajput regime, but the Rajputs conquered it and instituted their own system.

This ended rather quickly when the Muslims came. First the Arabs landed in Sindh and then the Central Asian Muslims began to march across the Hindu Kush, through the very convenient Khyber Gorge, which served as the gateway to India. The resistance of the scattered Hindu principalities was weak. The Rajputs were unwilling and unable to unite, so they were rather quickly subjugated by the Muslim rulers, who established a Muslim supremacy. The Muslim sultans found it easy to seize the supreme power, but they could do nothing about the way of life, the established stereotype of behavior, local attitudes and all the ethnic features that emerged here as a result of the passionate push.

Both the Muslims and the British who succeeded them had to put up with it, against their own immediate interests. Nothing could be done about it. If a Muslim sultan decided to break a Hindu custom, a cobra would bite him. It was a nuisance! Better not to break Hindu customs; and Muslim overlords learned that very well.

The English coped with such surprises, but they fell prey to another collision. The fact is that when big commercial cities like Bombay (a city of several million inhabitants) grew up, the untouchables, who alone could clean the streets, be janitors (no other Hindus, under threat of exclusion from caste, would take a broom in their hands), raised the price of their labor. But the Englishmen and Englishwomen who lived there could not even dust in their own homes, though it cost them nothing - they could use a rag and wipe it off; but then all the Indians would despise them and might become mutinous. So, a lower caste Hindu had to be hired to come and dust and take half her husband's wages.

Later these untouchables became very insolent. They staged a strike of sweepers and cleaners all over Bombay, and not a single scabbler could be found. They had the best lawyers. They chose talented boys from their caste and sent them to England, to Oxford and Cambridge. They went to law school, became lawyers, came back and defended their caste's interests very soundly in the courts. It turned out to be the most profitable thing to be a member of the lower caste! The income and work are both tireless and there is no competition. So, the new stereotype proved to be remarkably resilient: from the seventh and eighth centuries, when it was established, it survived into the twentieth century. But J. Nehru was a Hindu only by birth, but in his life, in his upbringing, in his profession, in his education, in everything he was a typical English journalist, and naturally he introduced the English order, and what will come of it, the future will show.

Tibetan version

A completely different impetus manifested itself in Tibet. Tibet from a small mountainous country, fragmented, divided, tribal in the VI-VII centuries, turned into a military monarchy of aristocratic type and seized the Great Caravan Route from China to Central Asia, that is, took control of the silk trade. True, this did not last long. Tibet was very sparsely populated compared to China, with no more than three million people, while China had about fifty-six million, but they nevertheless balanced each other out.

Tibet is a mountainous and isolated country, but relatively isolated. In the fifth century the western part of Tibet was inhabited by Indo-European tribes close to the Hindus. Darda and Mona lived there. They professed a light religion of Mithras, but were very tempted by witchcraft and sorcery: they cast spells, had some magic herbs, hypnosis, telepathy, incantations. They were full of all that, and they were of Caucasian type. And non-Chinese tribes fled to Eastern Tibet from South China, gradually ascending the great Brahmaputra River. In Tibet the Kyans met the Dards and the Monks.

A legend has survived about the origin of the Tibetans, who emerged from this ethnic contact, which anticipated Darwin. But unlike Darwin, humans are only half-monkeys; their ancestor-father was a monkey. The female mother was a rakshas, something like a leshog (rakshas are mountain forest demons). And it supposedly went like this.

Devil woman rakshas saw a beautiful monkey king, who came to Tibet to escape the Buddhist faith. She fell in love with him, came to him and demanded that he marry her. The poor monkey king was a hermit, a disciple of Avalokita. He didn't want to be with any woman, he came here to save his soul, but instead a witch in love showed up and demanded. Well, he flatly refused. So, she sings him a song:

O monkey king! Hear me, I pray you.

Through the will of an evil fate, I'm a devil, but I'm in love.

And, burned by passion, now I strive for thee,

Thou wilt not lie with me,

I will merge with the demon.

We will kill ten thousand souls at a time,

We will devour the bodies, we will lick the blood,

And, breed children as cruel as we are,

They will enter Tibet, and in the realm of snowy darkness

These evil demons will spring up cities,

And the souls of all men they will devour.

Think of me and be merciful,

For I love thee, come to my bosom!

The poor hermit, frightened by this insistence, turned to Avalokita and prayed to him:

O preceptor of all the living, love and good light, I must keep my monastic vow, Alas, the demoness has suddenly craved me, causes me pain, yearning and groaning,

And twists and turns and ruins my vow.

Source of kindness! Think, give advice.

Avalokita thought, consulted the goddesses Tonir and Tara, and said: "Become the husband of the mountain witch." And the goddesses shouted, "That's very good, even very good." And the monkey and the witch gave birth to children. The children were of all sorts, some were clever, resembling the hermit, others predatory, resembling the mother, but they all wanted to eat, and there was nothing to eat, because the father and mother, busy with self-improvement, did not care for them, and they began to cry out, "What shall we eat?"

Then the former hermit turned again to Avalokita and complained to him:

Master, I am in the mud, amidst a crowd of children, filled with poison the fruit that has arisen from passions, Sinning out of kindness, I have been deceived here,

My hands are knit with passion, and suffering oppresses me.

Cruel fate, and torment of spiritual poison,

And painful mountain of wickedness always languish me. Source of goodness, thou must teach, what must I do, that children may live.

Now they are always, like demons, hungry,

And when they die, they must go to hell.

Fountain of goodness, tell me, tell me quickly

And pour out the gift of mercy, pour it out, pour it out.

Avalokita helped him, gave him beans, wheat, barley, and all kinds of fruit, and said: "Throw them in the ground, they will grow, and you will feed your children." And so, from these children came the Tibetans.

The ancient legend quite accurately conveys a collision that is historically confirmed: the presence of two ethnic substrata that consolidated under a passionate impulse to create a single, monolithic and very vibrant, though multi-element, mosaic within the system Tibetan ethnos. The initial elements of this ethnos were, on the one hand, Dardic and Mono Indo-European tribes, and on the other hand, Mongoloid Kyans (Kyan is the ancient pronunciation of Qian). They were all spiritually united by a single faith, the Mithraism religion - Bon, but could not achieve political unity because each tribe did not want to know the supremacy of the other. But the Tibetans were fortunate enough to find a compromise. During the great decline of China in the 5th century, when there was a terrible massacre in the Yellow River basin, one of the defeated chiefs fled from his victors, the Tabgach (an ethnic group that came from Siberia), to Tibet. His name was Fang-ni. The Tibetans received him and his detachment and chose him to be their tsenpo. A tsenpo is not a king, not a chairman, not a president; in general, the highest Tibetan position with great powers and without any possibility of exercising them. Thus, the neutral alien Fan-ni became the head of all Tibetans with great prerogatives, but without real power because he had to reckon with both the Bon priests and the tribal chiefs.

Nevertheless, a unified organization was established, and the Tibetans began to spread westward, conquering the Pamir lands, and eastward. They didn't invade Shanshun, that is Northern Tibet, because it was hard to live there: the humidity was too high, the monsoons from the Indian Ocean came down in torrential rains when they reached the ridges of Northern Tibet, and they couldn't go further across the Kunlun, but in Northern Tibet it was so humid that even the bale turd rots immediately, it never dries, and if trees fell down, they immediately rot, and there was nothing to make fire with, though forests were plenty and beasts were plenty. So, the Tibetans moved east and west.

Each march had to be coordinated with all the tribal leaders and with the priests of the Bon religion; Tsengpo's hands were tied, and he sought real power and therefore turned his eyes to Buddhism. As I have said, Buddhist communities have always huddled at the foot of despotic thrones, because a despot who has no support among the people needs cosmopolitan and intelligent advisers and collaborators, unconnected with the people and indebted to the leader personally. The Buddhist community is always extraterritorial in its principles; the person who enters the community tears away all former ethnic, tribal, clan ties. This is why it is very convenient for a despot to use energetic Buddhists as his advisers or officials.

This experience was adopted by one of the tsenpos, Sronzangambo. He invited the Buddhists to him and told them that he would allow Buddhism to be preached in Tibet and thus hoped to gain opposition to the tribal chiefs and priests of the Bon faith. The collision is well known: the throne opposes the traditional aristocracy and the church. It has happened so many times in Europe. It ended badly for Sronzangambo, despite his exceptional energy. Sources tell of the construction of the magnificent Potala Palace; it appears in numerous paintings and still stands: it was built safely at the time. Around the palace lay torn eyes, severed fingers, hands, heads and feet of people who either did not want to accept the Buddhist faith or who disagreed with it. Then the tsenpo disappeared and Buddhism was persecuted and the king reappeared. The story is a dark one. I sat for several years on the Tibetan history of this period and came to the conclusion that it is very difficult to establish a chronology of this period, even with several versions - Tibetan proper, Chinese - and the fragmentary information that has survived in India (all translated into English and now available).

What is clear is that there were two parties in Tibet: the monarchist party, supported by the Buddhists, which wanted to overthrow the country to the detriment of the aristocracy and the traditionalist church; and the traditionalist party, the aristocrats, supporters of Bon and opponents of Buddhism.